Politics and protests make the university what it is today

March 4, 2019

SIU has always been a politically active university, made up of passionate students and community members who fight for what they believe in.

150 years ago, SIU was formed during a time of rebirth and reconstruction. The university served as a beacon of hope for a damaged nation which was recovering from the Civil War, but it didn’t mean life in southern Illinois was perfect.

Racism was still alive and well in the south – as was sexism – but because of the dedication of politically active student protestors, SIU is in a better place than it was.

Advertisement

1920s

Prohibition began in 1920 and continued into the early 30s in southern Illinois.

The Ku Klux Klan also flourished in the area during this time, according to Sam Lattuca, president of the Williamson County Historical Society, in a piece published in the Carbondale Times.

“By the time Prohibition took effect in 1920, the local county sheriff was already accustomed to turning his head away from the illegal production of alcohol,” Lattuca said. “That left many local Protestant churches fertile for coupling with the Ku Klux Klan and relying upon them for illegal alcohol enforcement when they resurged nationally in the early 1920s.”

Lattuca writes the Ku Klux Klan used their influence to take over southern Illinois, but their authority was challenged in 1924 by the Knights of the Flaming Circle, who joined forces with pro-alcohol gangsters.

This led to an all-out war in the towns of Williamson County and the National Guard was called in to end the violence.

Prohibition was not the only time southern Illinois saw unrest.

Advertisement*

In 1922 in Herrin, Illinois, the United Mine Workers network was in the middle of a strike. The workers were fighting for fair wages, adequate pay for dead work, and freedom from the oppression of mine owners and operators.

This strike turned deadly and became famous nationally as the Herrin Massacre.

Frederic D. Schwarz, a writer for American Heritage, said the Massacre took place in June when a group of strikebreakers from Chicago (who were not told they were strikebreakers) were brought to Herrin.

“Accounts differ as to who shot first, but gunfire was exchanged on the road and, shortly after, at the mine,” Schwarz said. “One strikebreaker and two strikers were killed, and a third striker was mortally wounded. Within hours, union men from surrounding communities were flocking to the mine, liberating guns and ammunition from stores as they went.”

The next day the strikers cornered the strikebreakers in the mine, forced them out and marched them into a barbed wire fence. The strikebreakers were lined up against the fence and told to run for their lives.

“As they clawed desperately at the wire, the union men opened fire, some fell down dead or mortally wounded; others escaped into the woods, where strikers continued to hunt them down,” Schwarz said. “An unlucky few were captured, marched to a cemetery, and shot; those who were still breathing then had their throats cut.”

The final death toll was twenty-one, with most of the survivors badly injured, according to Schwarz.

The strikers responsible for the violence were acquitted of all crimes.

1960s-1970s

Tension coursed through the veins of Southern Illinois in the 1960s. The civil rights, feminist, and anti-war movements were in full swing across the nation. The Vietnam war was raging and multitudes of young people were being drafted for the war every day.

The following is from an SIU security report posted on the SIU Department of Public Safety’s website:

On May 2, U.S. Army Recruiters were scheduled to conduct interviews in the Student Union. The recruiters set up their table at an assigned area which would afford them as much student traffic as possible.

At approximately 12:00 noon, a group of people surrounded the recruiters and then formed a “human chain” by linking arms. They thereafter refused to allow anyone access to the Recruiting Officers. The demonstrators were comprised of non-students as well as students and faculty members.

Immediately thereafter, a crowd began to form and grew to such proportions that the main hallway of The Union was blocked and became almost impassable. A number of students, most notably veterans, began to heckle the demonstrators. The situation quickly became highly explosive.

A student coalition was formed and approximately 150 people met to plan a “major confrontation” with the university, according to a May 6, 1968 article in the Daily Egyptian by Don Mueller and John Epperheimer.

The group suggested occupying and burning down the house of university president Delyte Morris, before ending the meeting.

On May 7 at 3:55 a.m., the Agriculture Building was bombed, according to a report filed by SIU DPS. This bombing was investigated by local police and the FBI, but the case was never solved.

Following several more protests and riots, a sense of constant unease plagued the campus. In 1969, an arsonist set SIU’s Old Main building on fire and left obscene messages on its chalkboards.

Marvin Kleinau, emeritus professor, said in a past interview with the Daily Egyptian he believes the burning of Old Main came as a result of anti-war sentiment toward Vietnam.

Kleinau said student activists who opposed the war sought ways to disrupt the University’s involvement and they were successful. At this time, Old Main housed the Air Force ROTC’s rifle range and burning down Old Main down got rid of the ROTC facility.

After Old Main was destroyed, the riots got worse in Carbondale. Students were forced to abide by a curfew and the militia and state police were called in.

One year later in 1970, SIU once again descended into chaos when students protested the expansion of the Vietnam war, racism and alienation on campus and the deaths of four Kent State students who were shot by the National Guard, according to a senior paper written by Katie Laux, a former SIU student.

The students had obtained a permit to protest by the city of Carbondale but violence ensued when a small number of the 1,500 student demonstrators began to block the railroad tracks next to Main Street, according to Laux.

At this time, the police and National Guard took action to disperse the protestors and sprayed the crowd with tear gas.

Laux said the students attempted to disperse and flee to campus but were pursued by police who continued spraying them with tear gas.

The mayor of Carbondale at the time, David Keene, declared a state of emergency and forced students to abide by a curfew of 7:30 p.m., and then-chancellor Robert MacVicar forbade any student gatherings involved more than 25 people, according to Laux.

Over the next several days, police violently attacked unarmed students and unnecessarily tear gassed student housing.

On May 12, thousands of students marched to the home of President Delyte Morris and threw rocks at the building. They marched to find MacVicar and threw rocks at the building he was in.

Laux said Raymond Dillinger, Jackson County Sheriff, along with Mayor Keene requested more National Guard and by the evening of May 13, 1,200 National Guard members were in Carbondale.

This was the final straw for students and they began to flood the ROTC building and Woody Hall. The police tear gassed the students again.

After this, the SIU campus shut down for the remainder of the semester.

1980s-2000s

While it wasn’t as far out, groovy, crazy, or wild as in the 60s, Carbondale saw its share of political activism in the 80s through the early 2000s.

Most protests during this time centered around the Bush administration and the United States’ involvement in foreign affairs.

Students gathered on campus to protest for or against abortion rights, voiced their opposition to unnecessary political involvement and war in Iraq, the Persian Gulf, and Afghanistan and advocated for the closure of Guantanamo.

They also protested KFC’s abusive and unethical treatment of chickens.

(See more: Chicken protests hope to end KFC practices)

Present Day

On May 2, 2016, dozens of students gathered in front of Faner Hall for a peaceful protest against some of the social issues impacting the campus. These issues included the budget crisis, homophobia, racism and academic diversity.

Violent threats were made before the protest, but protestors still marched. No incidents occurred.

(See more: SIU students come together for May 2 peaceful protest)

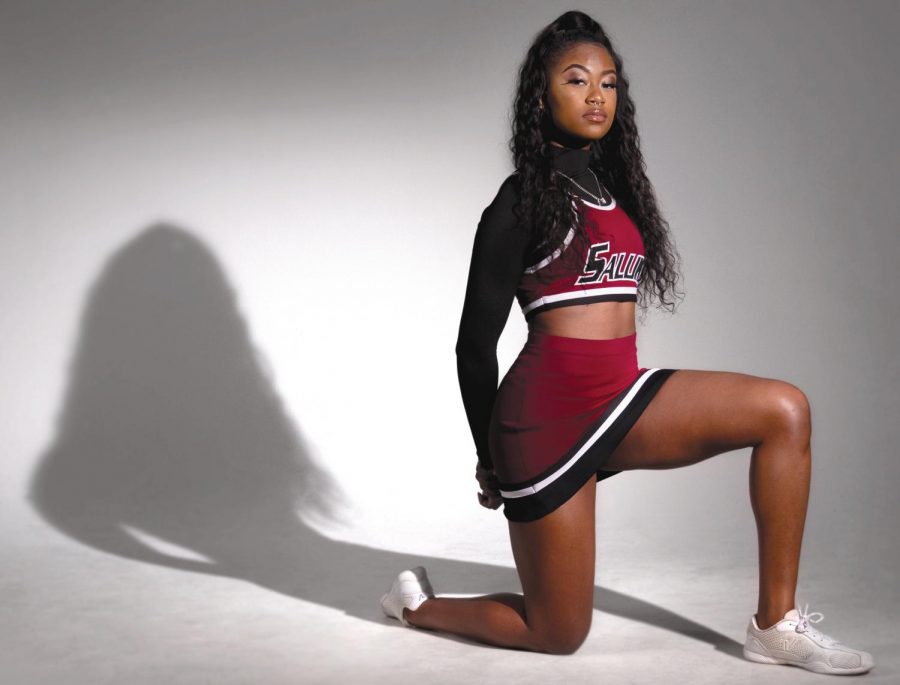

In October 2017, three SIU cheerleaders knelt during the national anthem at a football game to protest for civil rights for minorities.

(See more: Taking a stand on one knee)

The university responded by banning all displays of activism from student athletes, including cheerleaders.

The ban was later rescinded.

In Sept. 2018, students gathered to protest the university’s handling of an incident involving a student accused of being a neo-Nazi.

The student was found to have posted anti-Semitic comments in a Discord chat. Screenshots of the chat were shared on social media along with a flier accusing the student of being a neo-Nazi.

The university did not take action based on the accusations. Students criticized the university’s handling of the incident in comparison to its handling of the cheerleader protest, and this was one of the main focuses of the march.

Some may consider Southern as a party school, but it is also a politically active school filled with passionate students who are still protesting for their causes to this day.

Whether it’s standing up to nazis, kneeling for racial justice and civil rights, protesting the president, advocating for administrative change or saying no to a border wall, SIU students are engaged in the political climate and actively working to create social change.

Staff reporter Kallie Cox can be reached at [email protected] or on Twitter at @KallieECox.

To stay up to date with all your Southern Illinois news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement

Josh • Mar 6, 2019 at 11:20 am

No one actually looked at that Discord, but if they had they would have seen that that Nazi was armed and threatening “racial holy war”. His chats weren’t just antisemitism, they were threats.

patrick helmers • Mar 6, 2019 at 10:42 am

I recall marching against the colonial foreign policy of the time (curiosly still occurs today) in the late 70s. I wonder why there isn’t more of this now, kudos to Alaysia Brandy (you go girl). I’m surprised given the political climate, marches in Washington, Springfield and Illinois Ave aren’t more common. Just marshalled a #metoo event in Madision. Good to be active again.

Michael • Mar 4, 2019 at 10:34 pm

Love reading about Southern, Illinois’ old history. I hope SIU will once again become a

Becon of hope that encourages many to do

Great things.

To