Studying flaxseed, fowls: SIU scientists research ways to help prevent ovarian cancer in women

Senior physiology major Kara Starkweather, left, and Professor of Physiology Dr. Buck Hales pose for a photograph in a Life Sciences II lab Friday, Aug. 25, 2017, in Carbondale. The duo is using hens, which ovulate similarly to women, to research flaxseed as a dietary intervention in preventing ovarian cancer. “We understand that the major cause of ovarian cancer is the inflammation associated with ovulation,” said Hales. “Our goal is to turn ovarian cancer into a disease that women can live with instead of die from.”

August 30, 2017

On one innocuous day in 2006, Dale Hales was in a Whole Foods grocery store and a lightbulb went off in his head; he had an idea about how to help prevent ovarian cancer in women, and he was going to need two things — chickens and flaxseed.

Hales, a physiology professor, said he noticed something odd: there were eggs on the shelves with Omega 3’s, which are not naturally abundant in chicken eggs.

He set out to discover what the hens were fed to produce such eggs, and found it was flaxseed.

Advertisement

It’s been widely accepted in the scientific community since the early 2000s that inflammation is a precursor to identifying cancer, and since then, many scientists have began to study anti-inflammatories — such as Omega 3’s — as cancer prevention methods.

Flaxseed is the richest vegetable source of Omega 3’s, according to Hales.

“I think the fact that we are empowered, that we could affect our chance of getting a disease by what we eat, I think that’s a fantastic understanding,” Hales said.

Hens lay one to two eggs a day for two years, and many then develop ovarian cancer, Hales said.

This process is known as ovulation, an event which wounds the ovary. The ovary then undergoes “a tear and repair” cycle, and after many repetitions of inflammation, the ovary becomes susceptible to cancer.

Hales said the “hen laying-egg” model more closely resembles human ovarian cancer than any other model, aside from the fact human females ovulate just once a month.

Although many mice are used in scientific studies related to humans, Hale said he would have to engineer mice to get the cancer, whereas hens and human females naturally acquire it.

Advertisement*

According to the American Cancer Society, the five-year survival rate of ovarian cancer is 45 percent, and Hales said that rate is so low because in many cases, ovarian cancer is not detected until it is in its last stages.

Hales said early detection is difficult because the early stages of the cancer have no visible symptoms.

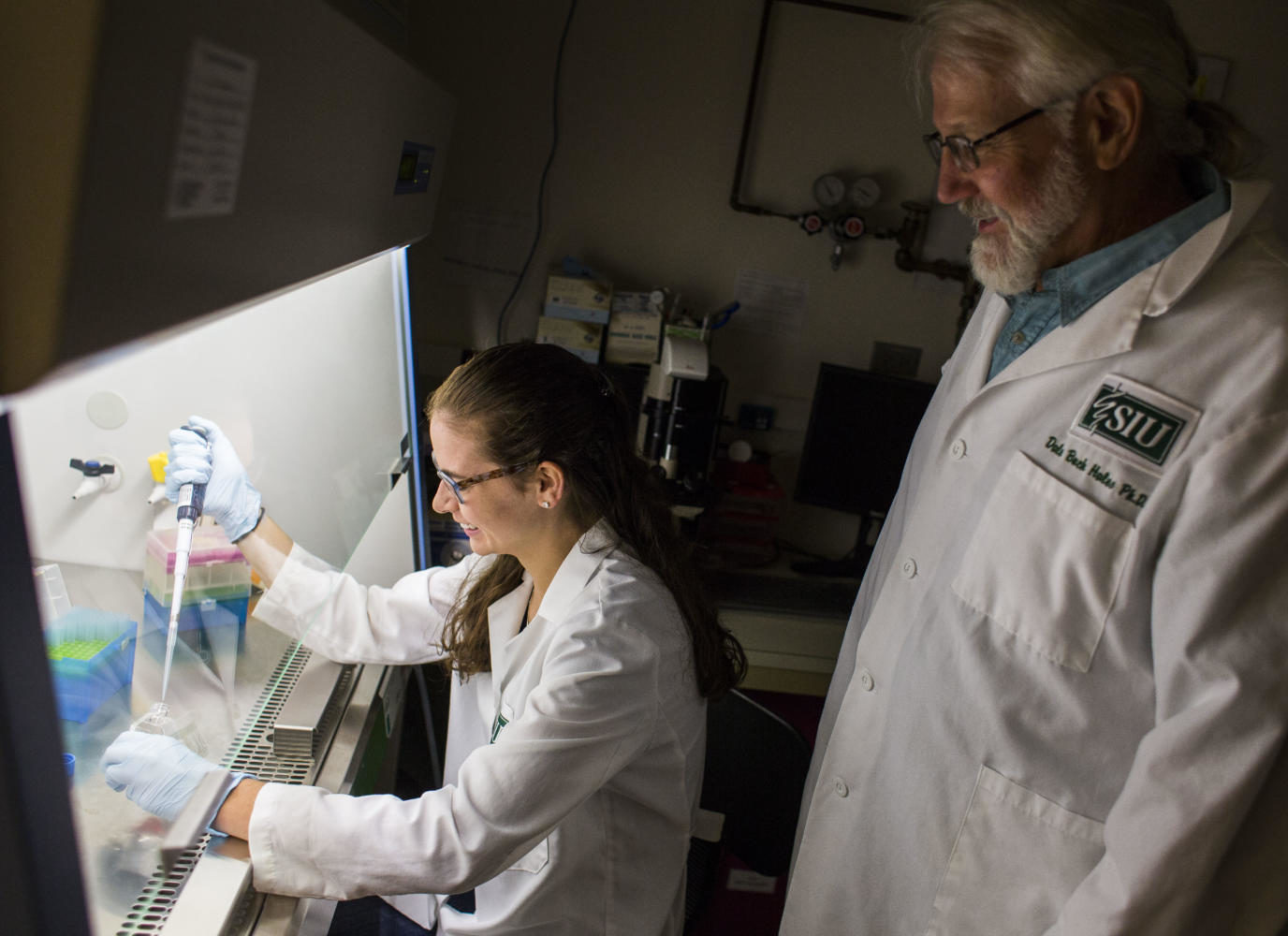

Senior physiology major Kara Starkweather, left, prepares to split some cells under the supervision of Professor of Physiology Dr. Buck Hales in a Life Sciences II lab Friday, Aug. 25, 2017, in Carbondale. The duo is using hens, which ovulate similarly to women, to research flaxseed as a dietary intervention in preventing ovarian cancer. “We understand that the major cause of ovarian cancer is the inflammation associated with ovulation,” said Hales. “Our goal is to turn ovarian cancer into a disease that women can live with instead of die from.” (Ryan Michalesko | @photosbylesko)

“I feel like the women feel like they’re a ticking-bomb,” he said. “So the women are highly motivated. If you could do something as simple as eating flaxseed to prevent you from getting ovarian cancer, why not?”

Because the late stage is so prevalently observed, it has been the focus of more studies, and not many have been conducted about ovarian cancer’s early stages, Hales said.

For his research, Hales buys hens that have been used for about two years to lay eggs. He said around that time, about 50 percent develop ovarian cancer.

He puts some of those hens on a diet consisting of flaxseed and others on a diet consisting of corn or other feed. The latter hens are used as a control group, or a group that should replicate the high incidence of cancer naturally.

About 25 percent of the hens in each group had ovarian cancer, Hales said.

The chickens fed flaxseed were only in the early stages of cancer, while the group fed corn were experiencing the late stages of cancer.

During the initial readings of these results, Hales and a graduate student of his at the time discovered a beneficial curveball: it wasn’t just the Omega 3’s in flaxseed acting an anti-inflammatory, there was also another component called lignin contributing to prevention of the cancer.

Lignin metabolizes estrogen into a compound that kills cancer cells, Hales said.

In 2015, nine years after Hales’ initial trip to Whole Foods, clinical trials began at the SIU Medical School in Springfield. Today, collaborators at the medical school issue flaxseed to women in ovarian cancer remission, and those women each must have a specific portion of flax each day.

Hales said one woman who has been 80 percent compliant in taking the flaxseed has been in remission for 27 months now, a result he finds significant because the cancer usually recurs after 16 to 18 months in 75 percent of women.

Clinical trials are now set to be expanded to the University of Southern Alabama at Mobile, and Hales said with that extra resource, trials can increase from the smaller number of patients they have in Springfield to hundreds.

His research has seen some obstacles along the way. Hales applied for federal funding but was denied the grant until he provides data using placebos, or women who would be be told they were being fed flax to cure cancer while in reality they are fed a non-working substance, similar to the study where some chickens were fed corn.

“I personally am a little bit conflicted about this,” Hales said. “Because we have something that we are pretty sure will prevent the disease from reoccurring, but we don’t give it to them?”

Hales said it could breech an ethics question to give women in remission false hope.

“By now, there are millions of women unfortunately who have had ovarian cancer,” he said. “On average, we know how long it takes to recur, so we think if we give them a treatment that exceeds that recurrence rate, then that would indicate that it’s doing something.”

One of the projects in his lab is to identity early detection markers of ovarian cancer.

Senior physiology major Kara Starkweather, left, prepares to split some cells under the supervision of Professor of Physiology Dr. Buck Hales in a Life Sciences II lab Friday, Aug. 25, 2017, in Carbondale. The duo is using hens, which ovulate similarly to women, to research flaxseed as a dietary intervention in preventing ovarian cancer. “We understand that the major cause of ovarian cancer is the inflammation associated with ovulation,” said Hales. “Our goal is to turn ovarian cancer into a disease that women can live with instead of die from.” (Ryan Michalesko | @photosbylesko)

“We’re able to target our therapy at prevention,” Hales said. “I believe that the cure for cancer is prevention.”

Hales and researchers have discovered four different biomarkers that have mostly been able to be replicated in clinical studies.

Kara Starkweather, a senior from Chatham studying physiology with a pre-med route, has been working in Hales’ lab since Jan. 2015, when she was a freshman.

“Coming to SIU, everybody talked about research,” she said. “Timidly, I walked in [to Hales lab] not knowing what I was getting myself into, but I just fit right in.”

It was a busy first week in the lab for Starkweather, who said she and the rest of Hales’ team went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to perform necropsies — non-human autopsies — on 800 chickens.

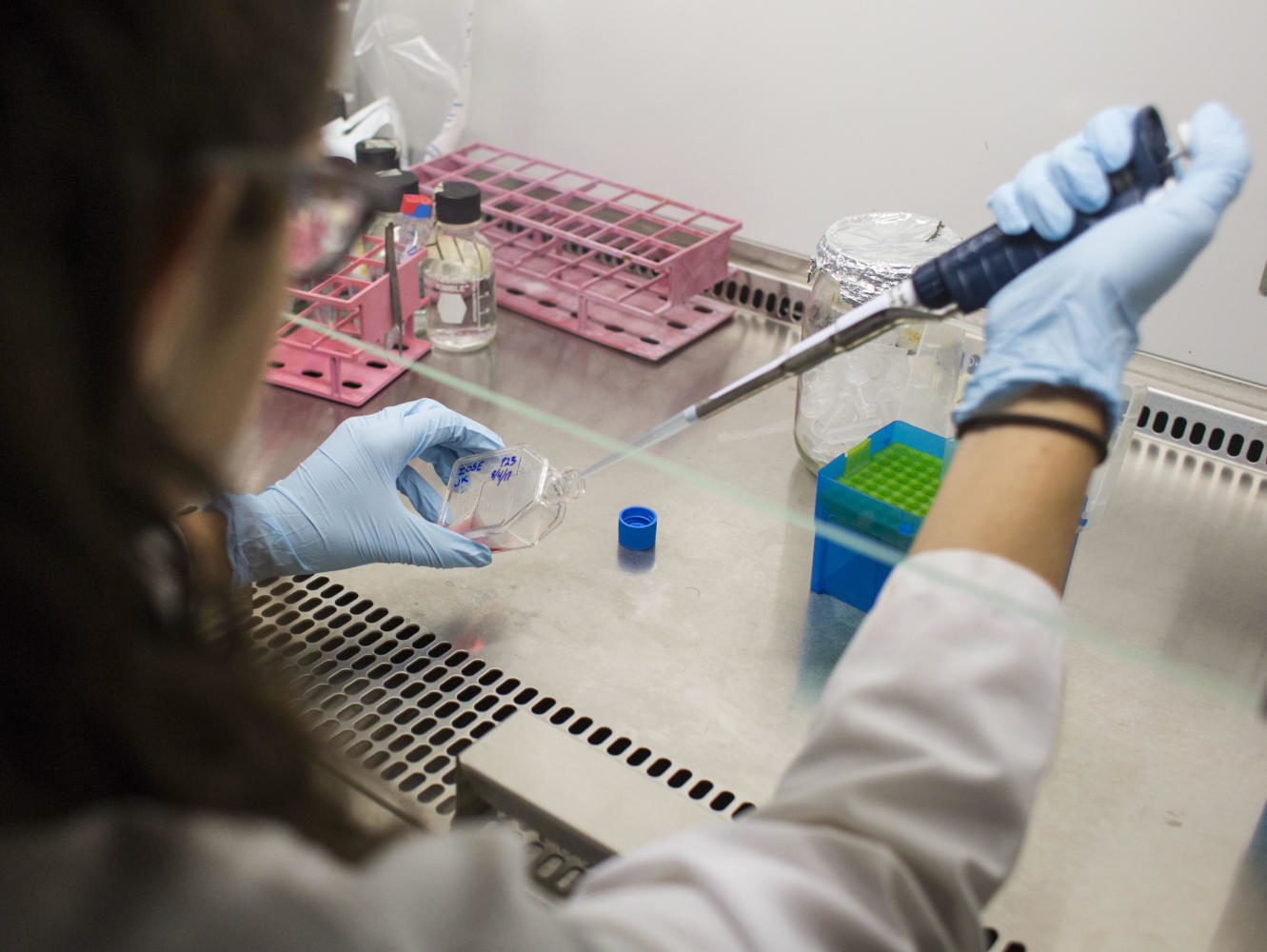

Since then, Starkweather has begun to study cancerous human cells from ovaries and even received a summer internship from the Simmons Cancer Institute to continue her research.

“Most students at larger universities won’t get the opportunity to work at the bench and do these experiments,” she said. “They may read about them, but there’s nothing better than to learn it at the bench-top.”

Starkweather said she is interested in pursuing a career in oncology, and one school she has said she is applying to is the SIU School of Medicine for the fall of 2018. She said she has considered continuing her research with the study in the clinical trials in Springfield if she is accepted and decides to go to the school.

Staff writer Cory Ray can be reached at [email protected] or on Twitter @coryray_de.

To stay up to date with all your Carbondale news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement