Chicago’s flawed system for investigating police shootings

December 8, 2015

It is a system seemingly designed to fail.

Chicago police officers enforce a code of silence to protect one another when they shoot a citizen, giving some a sense they can do so with impunity.

Their union protects them from rigorous scrutiny, enforcing a contract that can be an impediment to tough and timely investigations.

Advertisement

The Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), the civilian agency meant to pierce that protection and investigate shootings of citizens by officers, is slow, overworked and, according to its many critics, biased in favor of the police.

Prosecutors, meantime, almost never bring charges against officers in police shooting cases, seeming to show a lack of enthusiasm for arresting the people they depend on to make cases — even when video, an officer’s history or other circumstances raise concerns.

And the city of Chicago, which oversees that system, has a keen interest in minimizing potential scandal; indeed, it has paid victims and their families millions of dollars to prevent information from becoming public when it fears the shooting details will roil neighborhoods and cause controversy for the mayor.

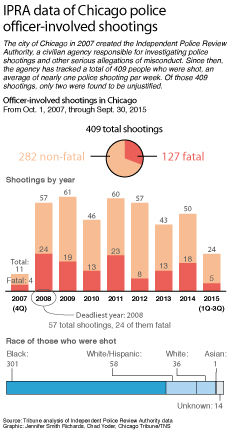

In many quarters, it’s common knowledge that Chicago’s system of investigating shootings by officers is flawed. But the Chicago Tribune’s examination of the system shows that it is flawed at so many levels — critics say, by design — as to be broken. IPRA’s own statistics bear that out. Of 409 shootings since the agency’s formation in September 2007 — an average of roughly one a week — only two have led to allegations against an officer being found credible, according to IPRA. Both involved off-duty officers.

Attorney Joseph Roddy, who was a police union lawyer for a quarter-century, said the IPRA figures suggest a deep problem.

“It’s hard to believe,” Roddy said in an interview. “Michael Jordan couldn’t make 407 out of 409 shots — even from the free-throw line.”

Lorenzo Davis was more blunt. Davis, a retired Chicago police commander who joined IPRA and became a supervisor, sued the agency in September after he said its chief ordered him to change his conclusions in six cases in which he found officers wrongly shot citizens.

Advertisement*

“The public cannot trust anyone who is currently in the system,” said Davis, who himself was cleared in two shootings while an officer years ago.

To be sure, much of the Police Department is honest and hardworking, and an officer’s job can be exceedingly dangerous in the city.

Fraternal Order of Police President Dean Angelo Sr. viewed the IPRA figures as evidence that police shoot only when they are forced to defend themselves or the public.

“Those types of numbers and statistics tell me that the city of Chicago has a very good police force,” Angelo said. “We’re scrutinized at a level never seen before. These [officers] are examined to the nth degree. The findings show they’re doing nothing wrong and they’re justified in their actions.”

But the 16 shots that struck Laquan McDonald in October 2014, and the dash-cam recording that captured the fatal shooting, has sparked protests across the city, led to a murder charge against Officer Jason Van Dyke, the firing of Superintendent Garry McCarthy and a Justice Department investigation of the Police Department — a reflection of the astounding failures it suggests. What’s more, the shooting of 17-year-old McDonald is only the latest case to underscore the city’s historic inability to deal adequately with police shootings and other forms of police misconduct. The department and this issue were challenges for the agency that preceded IPRA, the Office of Professional Standards, and for Richard Daley, the mayor who preceded Rahm Emanuel.

The root of the trouble, many observers of the system say, is a code of silence among many of the rank-and-file that contributes to a sense that the police can shoot with impunity. A federal jury even found that the code existed. In late 2012, in a lawsuit that stemmed from a drunken off-duty officer’s beating of a female bartender, the jury determined that the code protects officers who engage in misconduct.

Other issues contribute to the problem, including that patterns of complaints against officers are not considered during investigations.

“Almost every scandal, you’ll find a pattern of complaints,” said Craig Futterman, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who has been studying misconduct data for Chicago police for years. “The obvious thing would be to use that information. But we don’t.”

City officials often blame the city’s contract with police for that, as well as for being a broader obstacle to reform. And the contract does afford police protections ordinary citizens do not enjoy — what some call “super due process.” An officer involved in a shooting has, for instance, 24 hours before being questioned by IPRA, a crucial delay in a criminal investigation and an opportunity for officers to square their story with colleagues.

What’s more, the contract forbids officials from publicly identifying officers involved in a shooting unless they are convicted, though any officer who is charged would be named in court records.

But the city negotiates with the FOP, the union representing officers, and agrees to the terms. That, according to critics, suggests that city officials are more than willing to bargain away some of the rigor of an investigation as well as its transparency.

“The city comes out and blames the union contract for their hands being tied,” said Paul Geiger, who was an in-house lawyer for the union for more than a decade and part of the negotiating team for the most recent contract with the city. “Their hands are tied because they want them to be tied.”

Attorney Steve Greenberg, who has sued the city and the department on behalf of the family of a fatal shooting victim, agreed.

“It’s a cozy relationship where the police union gets to cover up wrongdoing among its members and the mayor gets to protect his image. Neither side cares about the truth or addressing corruption,” Greenberg said. “The entire system is built to impede the truth.”

The Tribune came to a similar conclusion in 2007. That year, reporters spent eight months examining the department’s police-shooting investigation practices, looking at more than 200 cases from the previous decade. The Tribune found that officials often rushed to clear officers, in many instances before critical evidence — including forensic evidence — could be analyzed, and even when evidence emerged later that contradicted an officer’s account.

Daley created IPRA the same year following a series of police misconduct scandals, hoping that it would improve investigations and convince increasingly skeptical residents that officers did not enjoy a separate standard of justice when they shoot citizens. He portrayed himself as the champion of police reform.

Since then, IPRA has come to be widely viewed as a part of the problem. Studies, including a December 2014 review by former federal prosecutor Ronald Safer, have found that its caseloads are too large, while critics and even some supporters say its investigators are overmatched in cases that can be complex. Although its investigators have subpoena power, officers still are reluctant to cooperate when they or their colleagues are being targeted.

The notion that IPRA is independent is also open to question, as the superintendent of police must sign off on discipline. Geiger and others said that even if IPRA wants to discipline an officer, a case may languish on the superintendent’s desk for months or even years.

After eight years in operation, IPRA this year for the first time sustained findings against two officers. In both cases, the officers were off-duty when the shootings occurred. In both cases, the incidents happened years ago, one of them in 2011, the other in 2012.

IPRA’s frailties have led lawyers to dismiss it as ineffectual, turning instead to the courts to hold the police and the city accountable.

A police training expert hired by plaintiffs in a federal court case submitted a report in 2013 that found IPRA was ineffective.

“Once again true reform was substituted for smoke and mirrors to fool the public,” Joseph Stine, a former Philadelphia police official, wrote after reviewing more than 300 IPRA cases. “It is my opinion that this sorry state of affairs has been permitted to continue because the city of Chicago does not want it fixed.”

Jennifer Smith Richards of the Chicago Tribune contributed to this report.

(c)2015 Chicago Tribune

Visit the Chicago Tribune at www.chicagotribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Advertisement