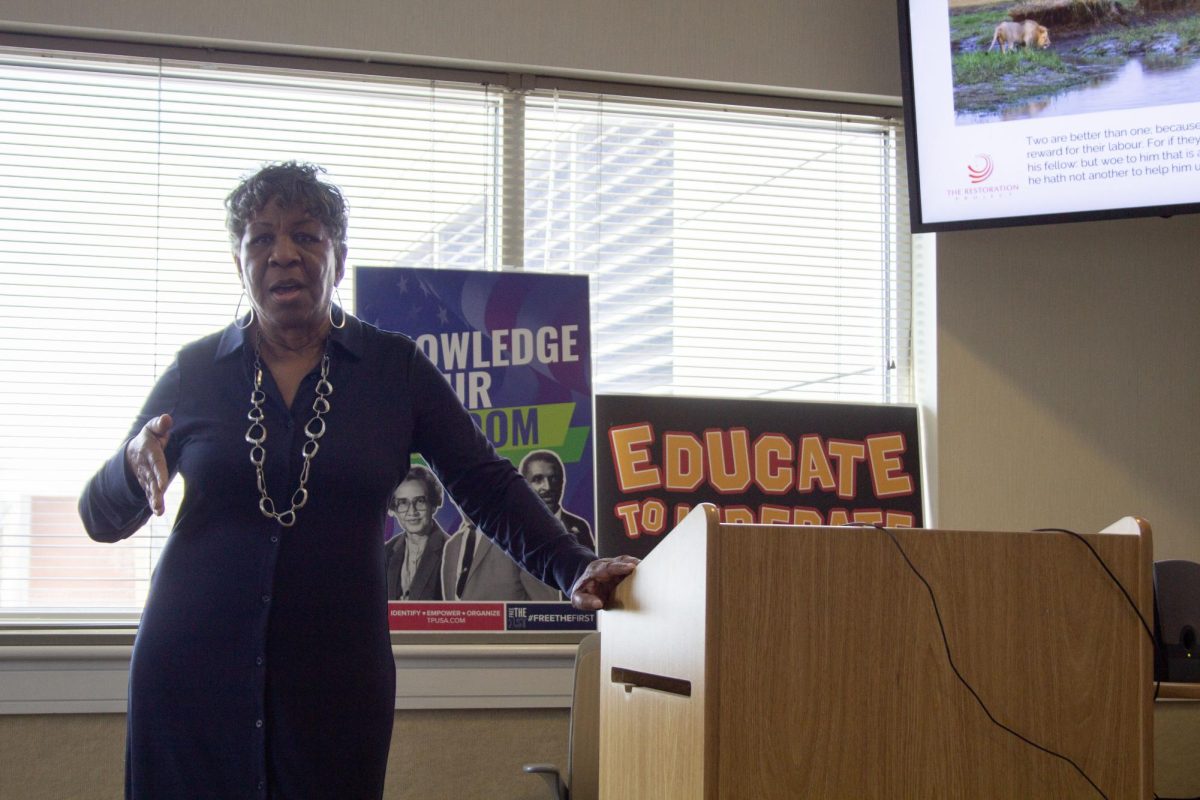

In a sparsely attended event on March 25 in Morris Library, Catherine Davis, a longtime anti-abortion activist and founder of the Restoration Project, argued that abortion is being used to systematically weaken the Black community. Hosted by Zachary Lochard, president of SIU’s chapter of Turning Point USA, the event framed abortion as a civil rights issue, tying it to constitutional protections and historical injustices.

While Lochard emphasized that the views presented were his own and not TPUSA’s official stance, he shared his personal anti-abortion convictions.

Advertisement

“I was born in Guatemala, a third-world country that does definitely have rampant abortion issues,” Lochard said. “This idea that only a certain class of people can be born into this world because they can afford it is ridiculous. I definitely don’t agree with it.”

Lochard, who has long aligned himself with conservative activism, talked about the importance of freedom of speech on campus and the need for open discussions.

“It’s really what Turning Point is all about. Having these opportunities is great, just in general, and then focusing more on the abortion issue,” he said. “It’s definitely one that I think everyone should have a voice and an opinion on, and we are just simply here to facilitate that conversation.”

Advertisement*

TPUSA is a student group that promotes conservative politics on college campuses, often focusing on free speech, limited government and opposition to progressive policies. The SIU chapter has been active in bringing controversial speakers to campus, sparking protests from students and community members who oppose their views. While TPUSA leadership claims the events are organized by outside groups, their chapter has consistently played a role in hosting and promoting speakers with anti-LGBTQ+ and other exclusionary rhetoric.

Davis, who has been involved in anti-abortion advocacy since 1997, delivered a talk centered on the disproportionate impact abortion has had on Black Americans.

“Abortion has disproportionately affected the African American community. It’s hard to overstate the lasting effects, and it’s hard to find the truth behind that. The numbers are manipulated in so many ways,” Davis said.

“We’re no longer having enough children to reproduce ourselves,” she said. “With our total fertility rate being at 1.4, it’s the best example I can give you of what happened to Native Americans. We can’t find them anymore because they’ve been so moved out of our communities.”

Davis claimed that declining Black fertility rates mirror the disappearance of Native American communities, citing a total fertility rate of 1.4. Recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data places the Black fertility rate at 1.639 in 2022, lower than the replacement level of 2.1 but not as low as Davis suggested. Additionally, the decline of Native American populations was historically driven by disease, displacement and violence, not solely by low birth rates.

She likened abortion policies to the Dred Scott decision, arguing that just as the Supreme Court once ruled Black Americans were not persons under the law, today’s legal framework does the same to the unborn.

The Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, issued by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857, ruled that Black Americans, whether free or enslaved, were not considered citizens and had no legal rights under the Constitution. The ruling reinforced slavery and denied personhood to an entire group of people based on race.

“In the Dred Scott decision, the courts ruled that Black people were not persons under the law. Today, the same reasoning is being applied to the unborn,” Davis said.

She said that both situations reflect a denial of personhood and equal protection, which, in her view, undermines the basic principles of human rights and justice.

Brittany Leach, an assistant professor of political science and sociology at SIU, who was not present at the event but commented on the broader pattern of this rhetoric in anti-abortion discourse, said the link between abortion and racial justice is frequently exploited within “pro-life rhetoric.” One of the key arguments often used is that abortion disproportionately targets communities of color, portraying the practice as a tool for racial extermination.

Arguments and imagery representing abortion as an attack on communities of color are employed somewhat commonly by the American anti-abortion movement, and can be found everywhere from billboards to legal opinions.

Leach said that an example of this can be found in Box v. Planned Parenthood, where Justice Clarence Thomas’s concurrence “portrays abortion as a tool of anti-Black eugenics.”

In this court case, Thomas’ concurrence argued that abortion laws disproportionately affected Black communities. He suggested that abortion was used as a tool to reduce the Black population, reflecting concerns about eugenics practices historically targeting marginalized groups. This interpretation sparked further debate about the racial implications of abortion laws.

Leach added that “one of the historians cited heavily in the concurrence rejected Thomas’ interpretation, as did many other historians, and even wrote an article in The Atlantic refuting the Justice’s opinion.”

Leach also highlighted a billboard campaign by the groups Life Always and The Radiance Foundation, which ran in 2011 and compared abortion to slavery. These billboards included statements like, “the most dangerous place for an African American is in the womb” and “black children are an endangered species.”

Leach said that, according to Professor Lisa Guenther who wrote the anti-abortion billboards, “these superficial claims that associate abortion with racism are themselves part of a racist political narrative that downplays the horrors of slavery and exploits Black trauma to recruit African Americans to the pro-life cause, while pushing a policy platform that devalues the lives of Black women and Black children once they are born by seeking to cut social welfare spending and, I would add, by opposing diversity, equity and inclusion programs.”

Leach’s research also touches on how claims about abortion’s impact on racial justice have been used to support anti-abortion laws.

“Claims about abortion’s dangers for Black and Latino children are used to push anti-abortion laws that prohibit race-selective abortions, even though claims that race-selective abortions are a problem are based on stereotyping and fear mongering,” Leach said.

While anti-abortion arguments often focus on the supposed racial injustice of abortion, Leach emphasizes that these claims do not align with reproductive justice, a framework developed by Black feminists.

She said that reproductive justice includes “three rights: the right to have children, the right not to have children and the right to raise your children in a safe and healthy environment.”

The core idea of reproductive justice is linking reproductive rights to broader struggles for social justice, and the reproductive justice framework often includes the right to abortion.

“In order to interpret abortion as a form of racial injustice, the pro-life argument is premised on the assumption that women of color are not capable of deciding what is best for themselves or their families,” Leach said. “If abortion of Black and Latino women’s pregnancies is a form of systemic racism or even genocide, that implies Black and Latino women are dupes or complicit in collaborating with a racist agenda. In my view, believing that women of color are incapable of judiciously exercising their reproductive autonomy is itself a form of racialized misogyny.”

Davis also linked abortion to a public health crisis, particularly among Black women.

“We’ve created an environment to make abortion friendly, rather than dealing with the true impact that abortion has had on women,” she said. “There’s an epidemic of breast cancer in the Black community that’s linked to abortion, but no one is talking about it.”

The American Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute and other major medical organizations state that there is no proven connection between abortion and an increased risk of breast cancer. Studies have found no causal relationship between abortion (whether induced or spontaneous) and breast cancer development.

Davis went further, blaming modern feminist movements for what she sees as the destruction of traditional family structures.

“To be the men that they were created to be, the protectors, the priests of their household. If we can bring that back, we can turn the tide in our culture. But I don’t blame men. I blame women. I especially blame the National Organization of Women and the whole #MeToo movement, because they trained women to be permissive…to break up the family,” Davis said.

Davis outlined two key initiatives her organization is pushing: a federal push to recognize personhood for the unborn and a demand for Congress to cut all funding to Planned Parenthood for allegedly violating civil rights laws.

“The only way we can end abortion in America is through recognizing the personhood of children in the womb,” Davis said. “It’s not going to happen legislatively, so we have to go back to the Declaration (of Independence), back to the Constitution as it was originally written.”

She also shared a personal story about her own abortions and how they led her to activism.

“I had two abortions myself,” Davis said. “I was like Scarlett O’Hara, I’ll think about that tomorrow, and so I didn’t think about it. But then I moved to Richmond, Virginia, and joined the church… I walked in, and they announced the topic was abortion, and I froze like a deer in the headlights.”

She recalled how members of her church prayed over her, pressing her down until they felt assured she would be okay. When they finished, one handed her a copy of “Grand Delusions: The Legacy of Planned Parenthood” and told her to read it and take action—an experience she says set her on the path of anti-abortion activism.

Leach notes that reproductive justice movements are already addressing the ways in which women of color are coerced into making decisions about abortion.

“If it is an intimate partner pressuring her, then that is a form of abuse, and reproductive justice is opposed to abuse. If it is her economic circumstances coercing her, then we need to fix the economic inequalities that create a coercive situation for her. If it is racism making her afraid to bring children of color into this world, that racism is the problem and it needs to be addressed. If it is lack of access to birth control forcing her to rely on abortion as a final back-up method, then we need to make sure all women have access to affordable contraception and other forms of healthcare,” she said.

Leach said that reproductive justice does not shy away from these difficult issues but works to identify and address the root causes of reproductive injustice in order to empower marginalized communities.

“Reproductive justice as a framework is particularly difficult for the political Right to co-opt,” she says, “because reproductive justice requires addressing all forms of injustice that affect women, people of color, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, poor and working-class people, or any other marginalized group.”

Davis also expressed a desire for a nationwide shift in perspective.

“I trust that abortion will end in the United States in 2025,” she said. “Once we recognize the personhood of the child in the womb, abortion ends. That’s where we are headed. People are beginning to realize the moral implications, and that gives me hope.”

She urged for a strong legislative stance against abortion, emphasizing that the United States must reaffirm the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as foundational laws.

“We just need for Congress to affirm the Declaration and the Constitution are the foundational laws of our land. Once they do that, abortion has to stop, because it does recognize children in the womb are persons, and that’s what I’m pushing for,” she said.

She continued, expressing her hope to directly address President Donald Trump about her concerns: “I covet your prayers that I’ll be able to get to President Trump and just ask him one question. Are you okay with the abortion industry using abortion to target one group of people based on the color of their skin? I want to play the race card, because it’s real discrimination.”

Davis stressed that the root of the issue goes beyond the legality of abortion and is deeply tied to racial justice.

“Whether or not we have the guts to do it, is the question, and that’s what I want to ask President Trump, do you have the guts to end the racial divide in this country by recognizing this?” she said.

Lochard echoed Davis’ concerns.

“I hope people just realize that abortion is not all that it’s cracked up to be. It harms women, it harms communities, and it harms men in irreparable ways,” he said.

Staff Reporter Annalise Schmidt can be reached at cgist@dailyegyptian.com. To stay up to date on all your southern Illinois news, be sure to follow The Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Instagram @dailyegyptian.

Advertisement