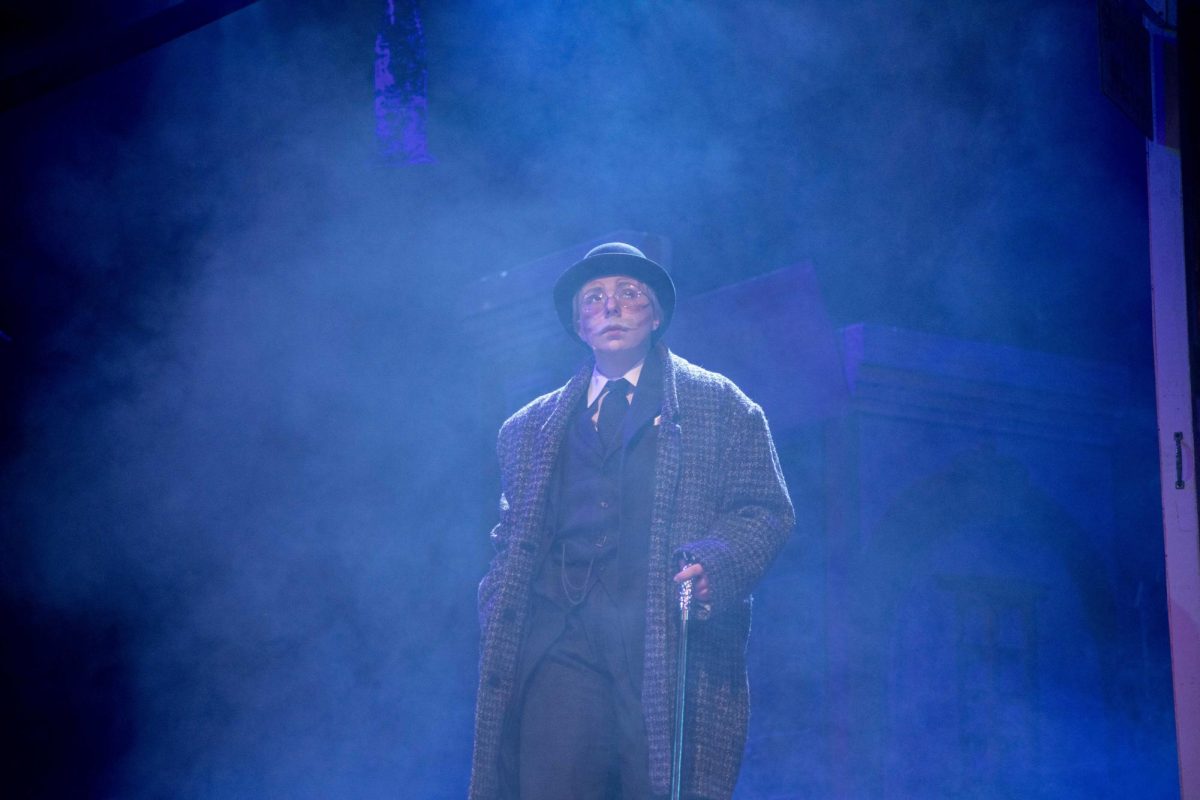

Charles Dickens’s holiday classic, “A Christmas Carol,” is well known to audiences everywhere. The work has been adapted time and time again, and SIU School of Theater and Dance brings a new take set in a place a little closer to home: 1920s Cairo, Illinois.

This Christmas classic with an American twist will be performing Dec. 5-7 at 7:30 p.m. and Dec. 8 at 2 p.m. in the McLeod Theater.

Advertisement

This iteration of “A Christmas Carol” is directed by Kesiena Obue, a Nigerian third-year MFA student in theater directing. This thesis turned play is based on an adaptation by the late Darwin Payne, who was a scenic design professor at SIU. The project has been in the works since December of 2023.

“I stayed very true to Darwin Payne’s adaptation. The only thing I changed was the setting and my interpretation of the story because I couldn’t really find my voice in the Victorian era as a Black woman,” Obue said.

The story follows Ebenezer Scrooge, played by Sawyer Richman, as Scrooge learns how his actions, business practices and cold humbug attitude affect those around him during the Christmas season, with the usual focus on his loyal clerk Bob Cratchit, played by J’kuion West, and the Cratchit family. The rest of the Cratchit family is played by Israeli Jones, Makyla Mobley, Quincy Smith, Yasmin Martinez-Powell and Kenzie Lozinski playing Mrs. Crachit, Martha Cratchit, Peter Cratchit, Belinda Cratchit and Tiny Tim, respectively.

Advertisement*

The play follows many of the same beats as the original story with several noted differences, including the cast’s renditions of several Christmas carols being occasionally used as emphasis in different scenes and some dancing which was choreographed by Darryl Kent Clark, a dance professor at SIU.

“It’s a style I call African total theater. In Africa, we tell stories with music and dance. We don’t have musicals, but our style is drama with music and dancing… Some things I could only tell with music and dancing. You know, it’s best to tell them through music and dance… It’s ‘A Christmas Carol.’ You can’t tell the Christmas story without carols,” Obue said.

Cairo is a town in Illinois’ own Alexander County that rests at the junction between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Sometime between the late 1800s and mid-1900s, Cairo was a thriving town with glowing prospects that in recent years has slowly been forgotten and ignored, suffering from river flood damages, two different mass population flights between the 1960s and 2020 and seemingly empty promises of help from the government.

Charles Dickens was not impressed with Cairo when he visited the town in 1842. He described Cairo as a “dismal swamp” at a time when many considered Cairo to be a gold mine. “A grave uncheered by any gleam of promise: a place without one single quality, in earth or air or water, to commend it: such is this dismal Cairo,” Dickens wrote in his journal documenting his travel through the Mississippi-Ohio junction.

Obue called Dickens’s musings on Cairo prophetic.

“He saw into the future of Cairo and everything he said about Cairo in his notes is what Cairo represents right now and he wrote that even before people started moving to Cairo,” Obue said.

After the Civil War, many Black people moved to Cairo and what followed was a surge of racial unrest and violence that led to the eventual economic collapse that many living in Cairo still feel today. There are places that locals will take you that are speculated to be parts of the underground railroad that thousands of slaves passed through to freedom. Cairo is truly an epicenter of Black history and resistance.

Popular Media would have you believe Cairo is a ghost town with no residence but there is much joy left in Cairo still. Cairo is home to a rich history. This is where the core of Obue’s version of “A Christmas Carol” is nestled.

Obue has built a strong personal connection with Cairo during her research for her thesis that allowed for a connection to “A Christmas Carol” that was not previously there, stating that Cairo calls to her.

“Every story I tell, it has to relate. I have to resonate with the story. It has to be personal to me, … I couldn’t relate with ‘A Christmas Carol’ and I like to tell stories that deeply resonate with me as a person. So when I was researching, when I found out Dickens came to Cairo, that was the confirmation I needed to set this play in Cairo,” Obue said.

The choice of place is echoed in every choice made by the crew. From casting to costuming to sets and lighting, little whispers of Cairo and its history as a town by the river are everywhere. Obue’s deep appreciation for Cairo has been accounted for, from her careful casting down to the smallest set piece.

Obue knew immediately who her Scrooge would be after the very first audition. Played by Sawyer Richman, this Scrooge is not quite like the others, and that was entirely by design.

Scrooge’s image is normally that of a tall lanky figure of a man. Tall and lanky, Richman is not and Obue felt that was an asset to the Ebenezer Scrooges’ character.

“I normally have my character analysis of what I’m looking for in the character. For Scrooge, I did not want to cast a tall, lanky Scrooge. I was looking for an actor who had the depth and range to capture … this big character but who can also be very vulnerable in those moments. When Sawyer walked in and auditioned, I was sold,” Obue said.

Richman was surprised during callbacks for Scrooge, unaware that his strong performance put them at the top of Obue’s list of potential Scrooges.

“I do not look or even really sound like a typical Scrooge… This is not a typical production of ‘A Christmas Carol.’ There are a lot of different themes. Kesiena has told me she doesn’t want a Scrooge who’s like … every other Scrooge … She wanted somebody who represented the smallness of Scrooge, which I’m very short, so that was good. That kind of clicked for me when she told me that,” Richman said.

The casting of an all-Black Cratchit family was very intentional on Obue’s part and adds a new layer of social commentary to the beloved Christmas tale, which normally has its main focus rest in the economic status of its characters.

“It was always my intention to have the entire family Black…My [adaptation] is different because I saw the story about race and class. My father would say, well, the easiest way to keep a man down is to make him poor, you know. From my research, that was what the white people did in Cairo. They had to make the Black people really poor so they could carry on with their agenda. I brought the race dynamics so it wasn’t just economics. For me, it was race, it was class, it was economics. That was the only thing I did different. I had to include race in the story. I feel like now, more than ever, we really have to address race issues,” Obue said.

Much thought was put into the costuming of each character. Motifs of joy and death were expressed through the careful choices of Aleka Fisher, a third-year MFA student in costume design at SIU. This production also served as a thesis show for her.

One noticeable costume choice is the colorful palate of the Cratchit family in contrast to the muted tones of the background and other characters. Their vivid colors signify the Cratchit family’s resilience and joy, making the best of their poor circumstances, which directly reflects the story of many Black people who resided in Cairo at the time.

Cairo’s history would be nothing without its ties to the conjoining Mississippi-Ohio river and it is not forgotten in this production. There is always the ambiance of the river nearby in the form of lighting or sound.

“The Cairo river is that one element that I believe washes away the history of Cairo. That place just keeps disappearing and it’s that river. Every time it floods it just comes and washes the history, the town away, memories away and all. That’s why historians are working to preserve (Cairo’s) history. So for me, I use the river as cleansing, not washing away, you know. I use it to cleanse the space, the universe of the play,” Obue said.

Two cast members have a very intimate history with Cairo. Malia and Israeli Jones grew up in Cairo for a period of time and have family ties to the area. To them, performing in the production and seeing Cairo depicted on stage in a time their grandmother would have been growing up is a full circle moment, according to Malia Jones.

“It very much does feel like we were meant to be in this show. Just seeing stuff that we remember and seeing pieces of our childhood and young adolescent lives. It’s really nostalgic,” Malia Jones said. “I feel like it connected us in a different way to the script and to the show.”

To honor Cairo and their connection to the town, Malia and Israeli Jones introduced another family member into their show in a very special way.

After the snow falls on the stage and the cast takes their final bows at curtain call, a soulful rendition of “This Christmas” plays as applause rings through the theater. This rendition is sung by the Jones sisters’ mother, Kimberly Jones, a gospel artist who was born and raised in Cairo. It’s one final homage to Cairo and its people before the show closes out and the deep red curtains fall behind the downtown Cairo arch set piece.

“She’s (Kimberly Jones) from Cairo and we thought it would be really cool to have a Cairo artist. We were like our mom did a Christmas song, she’s from Cairo,” Malia Jones said.

The serious tone of this rendition of “A Christmas Carol” is heavier than many have come to expect from this beloved classic, emphasized by the weight of the additional topics and themes Cairo brings to the story.

Underneath everything, the core themes still shine through even brighter with the new additional context to this adaptation.

“For me, the big theme is redemption, you know, because the world needs healing and that’s why this story is important to me. People need to see it and just feel like they could do better and leave feeling like we can do better for humanity, for society. No matter how far you’ve gone, you can be redeemed. You can become a better person,” Obue said.

Advertisement