Gun violence casts a long shadow across America. It kills some, injures more and leaves ripples of torment on the lives touched.

The numbers tell the story: Gun violence kills 45,738 and injures 96,935 on average nationwide each year. In Illinois alone, an average of 1,061 deaths per year are by gun-related homicide making it the 11th highest in the nation. Nearly 5,000 are wounded by guns, the 12th highest rate according to everystat.org – the largest gun violence prevention organization in the nation.

Gun violence costs the state of Illinois $18.6 billion each year, $625.5 million of that paid by taxpayers. Nationwide, it costs the United States $556.2 billion annually – which averages to $1,698 per person.

Advertisement

Illinois leads the nation in gun-control laws following California and New York with laws like prohibition on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines according to Everytown for Gun Safety.

It does not discriminate, touching cities both small and large. Carbondale, a small college town of just over 20,000, is no stranger to its toll. In the rural, southern Illinois town, police have responded to over a thousand shootings in the last five years.

Behind these numbers are real people grappling with loss and life after guns. Southern Illinois residents have lived and breathed it.

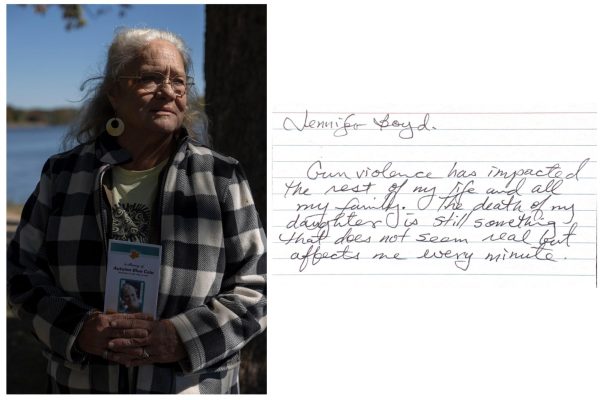

“Until it impacts you, you know, it’s just sort of a story out there,” Jennifer Boyd said.

Gun violence took 72-year-old Jennifer Boyd’s daughter and changed the entire trajectory of her golden years.

It was late evening on Friday, May 25, 2024 when Boyd received a call. The other end of the line was telling her that they had heard a shooting on the police scanner and were unsure if it was her daughter. The nightfall of Friday had rolled over to the early Saturday hours and Boyd was calling the police, rushing to the hospital, just trying to find out if her daughter was safe.

She arrived at the hospital to find Autumn Blue Cole, 43, her daughter, laying in the emergency room with her head wrapped up, shot in the left eye. Cole lived another day. Boyd held her daughter in the emergency room until she made the decision to let her go and pulled the plug.

Advertisement*

“I mean, it’s been five months. I almost can’t hardly believe it, like I’m going to wake up from this,” Boyd said.

Cole held a deep love for the outdoors and was a mother to her own two children: 10-year-old daughter, Ellie, and 19 year-old-son, Michael. Without their mother, Boyd will be Ellie’s primary caregiver.

“Not only that have I lost the child that I birthed, but now I’m raising her daughter and her daughter’s special needs,” Boyd said. “She’s got autism. She’s a lot and, you know, I have to be there, and so I’m changing the whole trajectory of my life because of this, this gun violence.”

Cole spent much of her time caring for her daughter, Ellie, keeping her alive. As a young child, Ellie underwent three open heart surgeries and still might need another. The impact reaches beyond for Ellie: difficulty in school, anger and outbursts all following the death of her mother.

“My message is, you know, how does this impact our children?” Boyd said. “You know, they have to live in a world where they fear guns. How sad.”

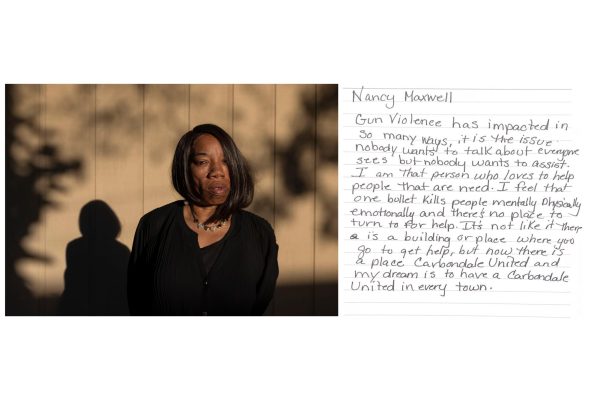

Nancy Maxwell relocated 331 miles south to the small town of Carbondale, Illinois in 1997 from Chicago. She thought the move would help her family escape the city’s notorious crime and it did. Until 2020 when her step-son was killed by a gunman. She now leads an advocacy program in Carbondale against gun-violence and racism.

In August of 2020, Maxwell was in a Zoom meeting when she got the call. Her step-son, Marquavion Purdiman, was shot and killed in nearby Marion, Illinois. She dropped the phone. The people on the other side of the line were still trying to talk to her, but all that didn’t matter. She rushed to the car trying to get to him. Upon her arrival, they had already transported Purdiman to the hospital. He was in critical condition.

“I will never forget seeing the yellow tape just like flying in the wind and this blood spot just on the ground,” Maxwell said. “They were telling us to move away and I’m like, ‘That’s my son. I’m trying to find out what happened to him.’”

It was the height of COVID and the limitation on hospital visitors had dwindled to none. Purdiman was in the hospital alone, but the parking lot overflowed with cars anticipating answers.

“He had no idea that the whole hospital parking lot was full of people out there praying and hoping and wishing that he’d make it,” Maxwell said.

The death of her step-son increased her desire for programs that would work to eradicate the reasons behind gun violence. But before his death, two young men planted the seed in her mind initially.

Five years ago, Maxwell was busy in a smaller, for profit t-shirt making business when a young man approached her to buy a shirt. The young man’s cousin had been killed and he was looking for a way to memorialize him. Three to four months later, another young man approached Maxwell with a similar story, except he was looking for a t-shirt to memorialize the first young man who came months prior.

That moment motivated her; she knew Carbondale needed a solution. She took to Facebook with the intention to get several organizations in the community to work together on one prompt – gun violence.

Maxwell was attending a sociology class at SIU when she heard of Violence Interrupters in Chicago: individuals who go out and de-escalate violence. This was her answer. So, each city council meeting, Maxwell was there asking what could be done to make this happen.

With no real answer, she began the process herself. Intensive time was spent submitting grant applications that she never thought would become a reality – until it did.

Chicago’s Violence Interrupters made the trip down to Carbondale to help mold Maxwell’s idea to fit the rural streets of southern Illinois. Given the name Carbondale United, the space works to eradicate gun violence and racism, but also provides an avenue of services for those in need.

Alongside being the director of Carbondale United, Maxwell now serves on the city council. Her wish is for Carbondale United to be a possibility in every town.

“One bullet does so much damage to so many people. You know, it kills more than the victim,” Maxwell said. “The victim, if the victim had children, parents, family, you know, the other family it’s like, wow, their family member maybe didn’t die, they’re going away for a long time.”

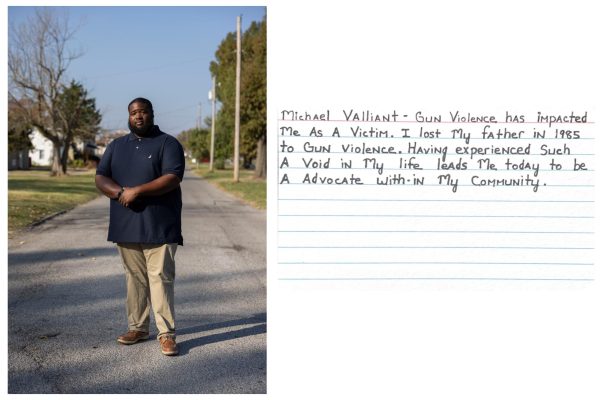

40-year-old Michael Valliant has grappled with the heavy cost of gun violence on both sides of the weapon.

Born and raised in Carbondale, he became a victim to gun-violence at an early age after his father was killed in 1985. As he went through life, he lost various family members and friends to gun violence, all impacting him in different ways.

At age 16, Valliant was incarcerated for first degree murder and was sentenced to 18 years in the Illinois Department of Corrections.

He was living beyond his years, he said. Selling drugs in the community that led him to develop a relationship with 26-year-old Michael K. Corney that later turned sour. The feud landed on Valliant’s doorstep in June of 2001 where the two exchanged verbal altercations, threats and a physical scuffle ensued.

Corney told Valliant he would go get a gun and kill anyone around – at the time, the only people nearby were Valliant’s family. Corney walked off from the scene towards his vehicle and Valliant followed with his eyes, so he went inside to retrieve a firearm. When he returned outside, Corney was fighting with Valliant’s mother, where he pushed her to the ground and cocked back his hand. Valliant shot and killed Corney before he could swing at his mother.

“I came to realize that I created a void in the world, but also within the lives of his family. It’s a situation that you can’t undo,” Valliant said. “Death is a permanent judgment.”

Valliant served 17 of the 18 years before he was released, but in those years, he spent time finding himself. He came to the conclusion that if he didn’t change his way of thinking, prison would always be a reality, and he wanted to prevent himself from ever having to go back.

“I’m motivated by that to try to create a change in the minds of people, in hopes that whatever I could do as far as outreach and trying to educate people about the different forms of violence that we can create a better society,” he said.

Now, back in the Carbondale community, Valliant is an advocate against gun-violence and a violence interrupter for Carbondale United. He steps in between momentary situations and offers a listening ear. His guidance has helped to disrupt the instantaneous emotion of anger that is a driving force behind violence.

“The lived experiences is what has shaped me to be who I am now. That is the driving force behind what I do now,” Valliant said. “I don’t think that had I experienced what I have, even been a perpetrator of violence and have to spend so many years in prison behind it, that has led me to be the person that I am today. So I breathe this thing every day, every day that I wake up, I breathe it.”

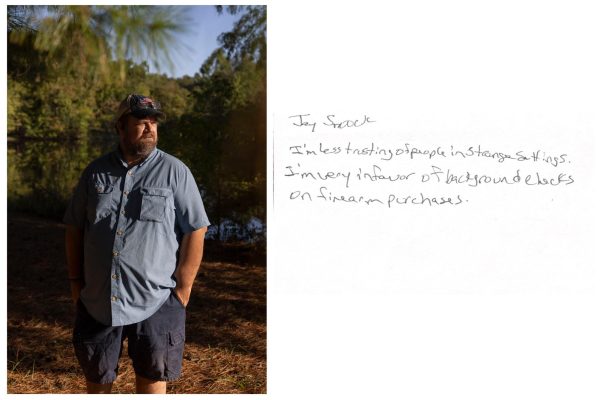

Jay Smock has carried the weight of gun violence through the death of a friend.

At age 19, he was pallbearer to his friend Kayce Steger after the Heath High School shooting of 1997 in Paducah, Kentucky. It was a Monday, and he had heard about the shooting quickly after it happened through the news. Perpetrator Michael Carneal opened fire on a group of students in a prayer circle in the school, killing three and injuring several more. Two or three hours later, Smock found out one of the three girls killed was Steger. The last time he ever saw her was that previous Saturday.

He met Steger through Law Enforcement Explorer Scouts, a division of the Boy Scouts. He stood in uniform for the funeral and carried her casket.

“Definitely kind of gives you a little realization just how fragile life can be,” Smock said.

For eight months, he saw the gun’s cost as a 911 operator in the western counties of Kentucky. It was everyday he heard calls of shots fired or someone had been impacted.

“I was glad I did it, sometimes I’m glad I don’t do it anymore,” Smock said. “You are beat by the end of the day.”

Now 46, Smock has moved to Carbondale in recent years and feels as though he’s not escaped the unsettling conversation of gun violence.

“Around here, it seems to have gotten worse,” Smock said. “Even in just the two years that I’ve lived here… it’s almost like you get a Facebook or notification alert darn near weekly.”

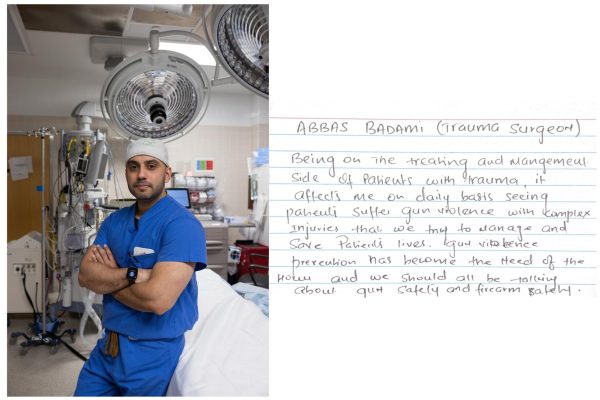

The lasting impact of gun violence greets 34-year-old trauma surgeon Dr. Abbasali Badami at the hospital’s sliding doors under the red emergency sign.

He was training at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York when a victim came in with four gun-shot wounds: one in his neck, one to the chest and two in the abdomen. Upon arrival, the victim was losing signs of life in critical condition. They cracked open his chest to resuscitate and rushed into the operating room to fix injuries to the victim’s lung, esophagus, kidneys, liver and bowel as a result of the gunshot wounds. With the response of Dr. Badami and the hospital, the victim recovered.

“I think that was the moment where, you know, I was like ‘Okay fine, I’m on the right track and you know, this is why we do what we do,” he said.

Badami’s job begins upon a patient’s arrival in the emergency room and ends in two ways: discharge or death. He is with them upon arrival, into the operating room and into the intensive care unit.

“When you manage those patients, you truly make an impact in their lives because trauma does not see a race or ethnicity. It’s like it can happen to anyone,” Badami said. “When that happens, you know, that person might be someone’s father, someone’s daughter, someone’s son.”

Originally from India, Badami grew up in Dubai before coming to the United States nearly a decade ago to practice medicine. He completed his surgical training in New York where he received robust training in split-second, life-or-death decision making. An interest in going somewhere that could benefit from trauma surgeon skillset landed him in the operating rooms at Southern Illinois Hospital in Carbondale.

Badami feels the impact outside of the operating room: in the road to recovery, in the post traumatic stress, in the lives touched around the victim.

“The trauma episode does not end once the patient leaves the hospital,” Badami said. “I might get busy with another patient, but the patients carry it with them outside the hospital and that they might carry it for a week, for a month, for a year, or for even more than a year, or for years, for decades. And that changes them, that changes them as a person, that changes their personality, that changes the outlook towards life. And sometimes people just live in constant fear.”

This is an ongoing series. If you are open to sharing your story, please contact lyleegibbs@gmail.com.

Editor-in-chief Lylee Gibbs can be reached at lgibbs@dailyegyptian.com or on instagram @lyleegibbsphoto. To stay up to date on all your southern Illinois news, be sure to follow The Daily Egyptian on Facebook and X @dailyegyptian.

Advertisement