‘My daughters are going to be OK.’ Then Trump phased out DACA

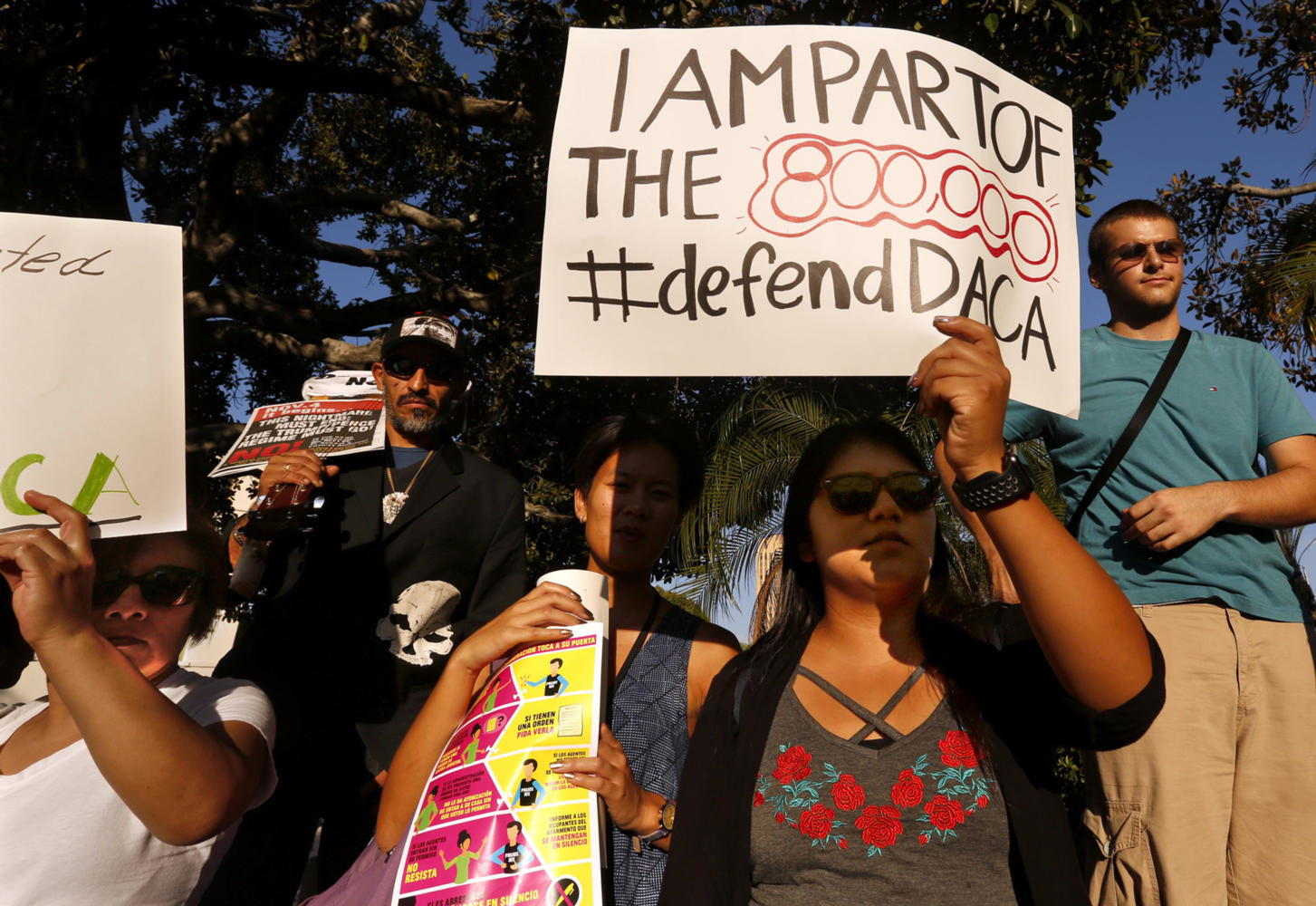

Los Angeles Harbor College student Brenda Soriano, second from right, and her mother Edilbertha Martinez, left, participate in a rally in support of the Deferred Action for Child Arrivals, or DACA program in Los Angeles on September 5, 2017. Brenda and her sister Diana Martinez are in the Deferred Action for Child Arrivals, or DACA program. The Soriano family are originally from Oaxaca, Mexico. Diana is studying to be an aerospace engineer and Brenda is studying to be a journalist. The girls came illegally to the U.S. at ages 3 and 7 in the back of a van through Tijuana. (Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

September 20, 2017

Behind closed doors, Bertha Martinez and her husband, Victor Soriano, often discussed how they would tell their oldest daughter that she was in the country illegally.

“We didn’t want to hurt her,” Soriano said.

Paying someone to sneak 7-year-old Brenda and 3-year-old Diana across the border in the back of a minivan had seemed like the right choice in 2002.

Advertisement

In their L.A. apartment, the girls’ happy portraits and their many certificates of achievement were testament enough that coming to the U.S. had been good.

But as Brenda grew older, as she headed toward college and work, the potential consequences of her legal status weighed more heavily on Soriano and Martinez.

Obama’s 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program relieved the pressure for this couple and thousands of other parents, many in danger of deportation themselves.

Their children — nearly 800,000 — were given the chance to drive, study and work without fear of deportation.

“My daughters are going be OK,” Martinez thought.

Then came the Trump administration’s announcement that it would phase out DACA — and day after day of mixed messages since.

These are the stories of parents, whose children’s futures again are in limbo.

Advertisement*

___

Bertha Martinez remembers the day Brenda received her Social Security card. Same with her driver’s license, her permit to work.

“She was so … hungry to do everything,” Martinez said.

Brenda took a job at a nonprofit helping kids in Watts. She enrolled at Harbor College to study journalism. Her sister Diana became a Starbucks barista and went to Cal State Long Beach for mechanical engineering.

At home, ifs and maybes went out the window.

“When you’re a writer at the Los Angeles Times … ” Martinez would tell Brenda.

“When you’re an engineer at Northrop Grumman … ” she would tell Diana.

When Martinez heard “DACA” and “revoke” on Spanish-language radio, she wanted to run to her girls, to shield them.

“That dream we lived, the one that we couldn’t believe because it was too good to be true, it now seemed like a nightmare,” she said.

Martinez comes from an Oaxacan village of 15 houses. She and her husband left Oaxaca first for Mexico City, where they opened a T-shirt business, which had five workers after two years.

“The United States never crossed our minds,” Soriano said.

Then one morning, three men showed up and held a gun to Soriano’s chest. They stole more than 1,000 shirts and left the couple broke.

Soriano fell into a deep depression. “Every day, for like 10 months, he only slept,” Martinez said.

When he heard about a relative in the United States, he decided that he too would go north. He would work, save up for a year, and then start a new business in Mexico.

But in Gardena, where he found a good job making wooden doors, life overall seemed brighter. He pictured his girls at a nearby school, speaking English.

In 2002, Soriano paid $1,900 to sneak the girls across the border at Tijuana and $2,000 to help his wife cross nearby on foot.

In the U.S., the Soriano sisters grew up in different worlds.

Brenda was lonely and terrified of school because she didn’t speak English. She begged to return to Mexico.

“I cried from third grade up until middle school,” she said.

Ask Brenda what her goals are, and she says first: “a big family party” — with relatives the family hasn’t seen since 2002.

Diana can’t remember Mexico. Her English is accentless, her Spanish broken. Portraits of her abuelitas spark warm feelings, she said, but “my memory started here.”

___

Betty doesn’t want her last name used because she’s afraid she’ll be found and deported. Her children were 6 and 8 when she got them tourist visas, packed their bags and told them she was flying them to Disneyland.

In Mexico, Betty led a life of privilege. She owned two homes, had several cars and maids. Her children, Jose and Itzel, attended a top private school that chauffeured them home each day.

Betty helped run a luxury hotel, and in 1993, when she was 28, the hotel sent her to L.A. for three months to learn English.

In Mexico, Betty said, men often harassed her. Her husband was emotionally abusive.

“I came here and I instantly felt at peace,” Betty said of L.A. “I knew life for me and my children would be better.”

She and the children moved to La Mirada, where she found work as a nanny.

“I thought they’d come here and live the life of a prince and a princess,” she said. “Like a Walt Disney movie with a happy ending.”

Betty adjusted to life working for a wealthy Korean family. She learned to clean houses, clip coupons, wash other people’s clothes.

When her mother flew in to visit, she was appalled at how her daughter was living.

“She said she would never return,” Betty said.

The single mother was unfazed. She pushed her kids to focus on school.

When their visas expired, she paid no mind.

“I lived in a bubble,” she said. “I thought I had done nothing wrong.”

An English teacher once asked about her journey north. Did she come by foot? Did she swim across a river?

“That’s not me,” said Betty, dumbfounded. “I came on an airplane.”

Immigrant rights seemed like someone else’s fight.

She saw no reason to tell the kids about their legal status. She didn’t think it mattered.

Then Itzel reached high school and tried to take college courses. To pay in-state tuition, she needed to prove she was a resident.

At age 16, Jose began to ask for his Social Security number. He wanted to drive and work and travel like his friends.

“I’ll give it to you soon,” Betty would tell him. “I need to look for it.”

What she needed was to buy herself more time.

Betty was terrified. She called the Mexican consulate and immigrant aid organizations. Their advice was of little help. She told her children: “If someone asks where you were born, say you were born here, say that you don’t know.”

One day in 2009, Betty found out about Dream Team LA, an activist group beginning to fight for the “Dreamers,” immigrants who were brought into the country illegally as children or had stayed past their visas, like Itzel and Jose. For the first time, at a meeting, Betty and Jose heard illegal immigration discussed openly.

“We found a sense of community there,” Betty said. “My son lost his fear and felt part of a movement.”

The two joined in marches, rallies and acts of civil disobedience — in L.A., Sacramento, Washington, D.C.

By the time DACA took effect, Betty was organizing other parents. Jose, 26, had a job at a nonprofit helping labor unions and farmworkers. Itzel had married an American and become a permanent resident. Betty felt a sense of relief for them, but worry for herself and others.

“So many people choose to do nothing, like I did for so long,” she said. “But … we have to defend ourselves.”

When she heard about DACA ending, Betty wasn’t surprised. The night President Donald Trump was elected, she had walked the streets of Los Angeles, sobbing.

“My soul shattered for my son,” she said.

Today, when she sees Jose, she feels hope. He is strong and funny. His employer has promised to do everything possible to protect him.

“I can’t make castles out of air when I’m walking on land mines,” Betty said. “But I think he’s going to be OK.”

___

(c)2017 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Advertisement