Judge rejects Chicago mayor’s assertion that emails are exempt from disclosure

June 1, 2016

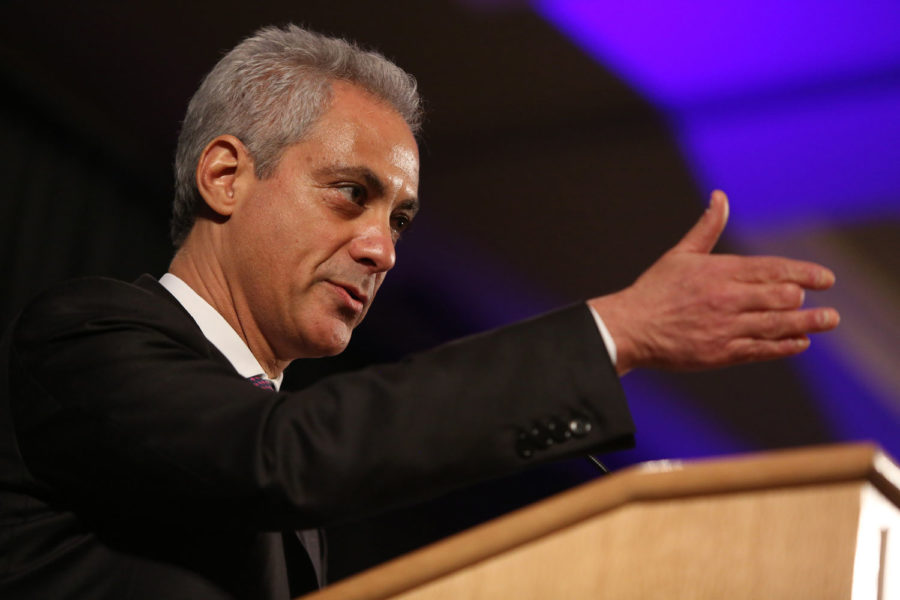

A Cook County judge ruled in favor of The Chicago Tribune on Tuesday by declaring that Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s emails, texts and other communications are not exempt from disclosure simply because they are transmitted over private devices.

The judge denied Emanuel’s motion to dismiss the Tribune’s lawsuit, which alleges the mayor violated the state’s open records laws by refusing to release private emails and text messages about city business.

The Tribune asked a judge to order the mayor’s office to comply with a state Freedom of Information request and produce the documents. The lawsuit, filed in September, also seeks to have Emanuel declared in violation of the Illinois Local Records Act if he failed to preserve emails and texts he sent or received relating to city business.

Advertisement

The ruling comes down as the issue of personal email use by government officials remains at the forefront of the presidential campaign. Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton has continued to face questions about her use of a private email server during her time as secretary of State. Last week, the State Department’s inspector general found Clinton broke department rules when she used private email for government business, concluding she created a security risk and violated transparency and disclosure policies.

The former secretary of State has maintained she did nothing wrong. Likewise, Emanuel has said the city complies with records requests and that he conducts city business on his government devices and accounts.

City Hall asked the judge to dismiss the Tribune’s lawsuit, arguing the requests constitute an “unprecedented and unreasonable invasion of personal privacy” and the “alleged emails are not public records.”

The mayor’s office had argued that the law allows plaintiffs “to enjoin a public body from improperly withholding public records. But a public body cannot ‘withhold’ a record that it does not possess. Indeed, Plaintiff does not identify, nor does the Act provide, any means by which a public body such as the City could force its officers and employees to grant it access to their privately owned accounts and devices.”

But the judge disagreed.

“There is no merit to defendants’ argument that the mere storage of communications pertaining to the transaction of public business on personal electronic devices (or in personal email accounts) categorically shields those communications from the FOIA,” Cook County Circuit Court Judge Kathleen M. Pantle wrote.

She ruled the FOIA law does not distinguish between records kept on publicly funded devices and private ones.

Advertisement*

The judge said it should be up to the court to decide whether the communications are “public record” and wrote that communication on private devices or within private accounts “does not ipso facto mean that the communication is personal in nature.”

The city vowed to keep fighting the Tribune’s lawsuit.

“While we are disappointed in the ruling, the judge only ruled on the motion to dismiss and not on the merits. The City will continue to vigorously defend this case,” Bill McCaffrey, a spokesman for the city Law Department, said in a statement.

The Tribune, meanwhile, welcomed the ruling.

“It’s wrong for a government official to claim that if they conduct business on one phone and email account it’s a public document, but if they use another phone or account to conduct the same business it is a private matter,” Bruce Dold, the Tribune’s publisher and editor-in-chief, said in a statement. “We are committed to pursuing this case to the end.”

The judge gave the mayor’s office 28 days to answer the complaint.

“This surge of electronic forms of communication has been a huge challenge for public information and transparency and public access,” said Dan Bevarly, the interim executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition.

When public officials use private devices or message accounts, Bevarly said, “it automatically adds a whole layer of suspicion.”

Cases involving elected officials trying to shield electronic correspondence on private devices from public view is becoming increasingly common, he said, and including high-profiles cases stretching from New York to Florida.

The Tribune’s lawsuit claims the mayor’s office in recent years has been uncooperative with FOIA requests. The lawsuit alleges Emanuel’s use of private phones and personal email allows the mayor to conduct city business out of public view and contributes to a “lack of transparency.”

The city’s position that turning over the messages would be an invasion of privacy is up for debate, the judge ruled, because the law only protects against “unreasonable” invasions of privacy, not all. The courts would need to examine the requested communications to determine if the records should be produced, similar to weighing whether or not to issue a search warrant.

Illinois law says written communications by government officials are subject to Freedom of Information Act requests. The law covers “electronic communications” but does not spell out the rules for the use of personal email and text messages on private cellular phones, experts said.

Bevarly said some states, including Florida, have recently adjusted their laws to include language about conducting public business on private devices.

When the Tribune filed its lawsuit in September, its attorneys sent a letter to the mayor’s chief lawyer requesting that “any and all documents, information and electronic data (including emails and text messages) that are or may be relevant to the Tribune FOIA Request … are preserved and retained.”

The suit itself sought an order declaring that any failure to retain such electronic communications would violate the state’s open records act. In Tuesday’s ruling, the judge wrote, “The Local Records Act provides in pertinent part that public records cannot be damaged or destroyed except as provided by law.”

The Tribune lawsuit against Emanuel grew out of a FOIA request in June. Tribune reporter David Kidwell sought emails, text messages and other electronic communications between Jan. 1, 2015, and June 30, 2015, related to the city’s scandal-plagued red light camera program.

The Tribune’s reporting led to a bribery indictment of a former city official and revealed inconsistent enforcement and lax oversight.

The Tribune’s FOIA request also sought communications during the same period that included the mayor and Michael Sacks, CEO of a Chicago-based hedge fund, who has donated to Emanuel’s campaigns and was named to lead World Business Chicago, which Emanuel formed to try to bring business to the city. The Tribune, in its reporting, has sought to learn more about Sacks’ role in advising the mayor on economic development and other public policy issues.

Kidwell’s request also sought all texts and electronic communications to or from Emanuel between May 1, 2015, and June 30, 2015. It specified that the entire request applied to correspondence on city and personal communication devices.

In its July 15 response, the mayor’s office agreed to produce some logs. It said some of the request was “unduly burdensome,” an exemption under Freedom of Information Act law, because it would require workers to produce thousands of emails. And it said it had no texts, which typically are not stored. The mayor’s office also said it had no records responsive to the request for emails and texts in which Emanuel conducted city business on personal devices and argued it was not required under the law to produce those.

In 2011, in a case involving members of the Champaign City Council, Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s public access counselor determined that written communications about government business on personal email accounts and private cellphones are subject to FOIA. In essence, the office said it was not the device that mattered but the person using the device and the content of the communications.

The case went to the Illinois Appellate Court in Springfield, which took issue with some aspects of the attorney general’s opinion. But the court agreed that emails and texts on personal devices sent by council members during a public meeting were subject to FOIA.

Judge Pantle cited that case in her ruling.

Anticipating more disputes over the issue, the appeals court also suggested that the General Assembly clarify the law. Despite that recommendation, lawmakers have yet to pass legislation to resolve what is considered a public record under the Freedom of Information Act.

Several public statements by the mayor have referred to his use of electronic communications. In 2011, he told the Tribune he used a cellphone for work but would not say whether it was a city-paid cellphone.

(c)2016 Chicago Tribune

Visit the Chicago Tribune at www.chicagotribune.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Advertisement