4 years after Benghazi, are we protecting US diplomats any better?

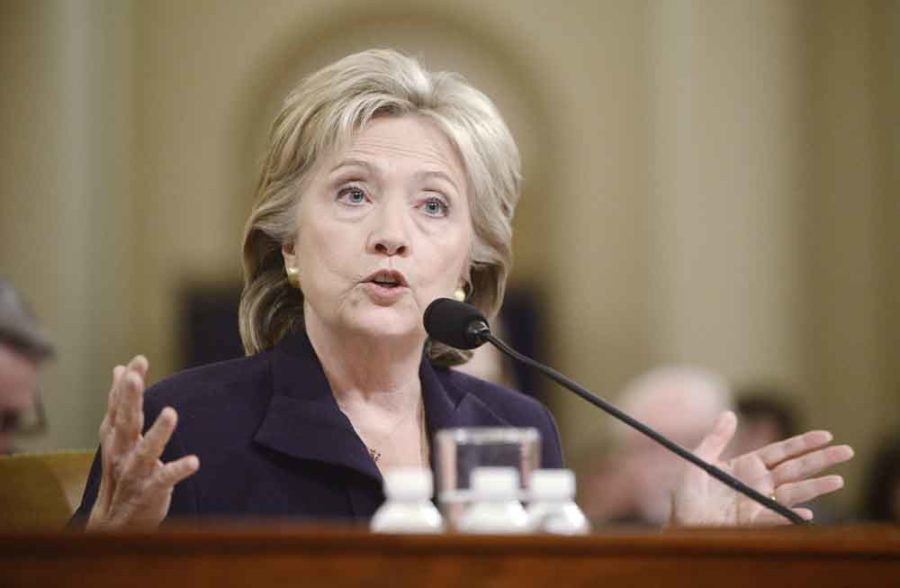

Former Secretary of State and Democratic presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton testifies before the House Select Committee on Benghazi on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on Thursday, Oct. 22, 2015. (Olivier Douliery/Abaca Press/TNS)

September 10, 2016

WASHINGTON — Four years after the Benghazi terrorist attacks killed four Americans on the 11th anniversary of 9/11, debate still rages over whether the United States has done enough to protect its diplomats overseas.

The latest salvo in the battle was spelled out in whistleblower complaints by a former State Department security expert, who alleged that steps to prevent chemical, biological or radioactive weapons from penetrating U.S. facilities overseas are flawed.

Dr. Leonard Y. Cooper filed his two complaints a year after the Benghazi attacks. In them he alleged that his State Department contract had been terminated because of his criticism of the security measures.

Advertisement

The Office of Special Counsel, the federal agency meant to protect whistleblowers governmentwide, ordered a full investigation into the complaints, determining that Cooper’s expertise and position at the State Department put him in a position to know what he was talking about.

In the end, the office took no position on the validity of Cooper’s criticisms, closing the case in June after requiring the State Department to provide a detailed response to his allegations and then allowing him to respond to the State Department filing. The entire packet was then forwarded to the White House, as required by law. Because of the sensitivity of the allegations, the office decided not to post the file on its website.

That is unlikely to be the end of Cooper’s allegations, however. His attorney, Tom Devine, said Cooper was arranging to share his concerns with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

The State Department defends its actions in the case and its security precautions overseas.

“Embassies and consulates serve on the front line of U.S. diplomacy. As such, we work hard to provide secure, safe and functional facilities,” State Department spokesman Mark Toner said in an emailed statement. “We recognize that sometimes our national security interests require U.S. diplomats to work in difficult and even risky places. But we do our utmost to ensure the safety of our diplomats and our locally employed staff.”

Cooper’s claims are highly technical in nature. One of the problems, he said, is a fundamentally flawed “boilerplate” design, developed and used universally for diplomatic buildings by the State Department since the early 2000s.

The second problem is hauntingly Libya-specific, a direct result of the State Department’s response to the Benghazi attacks, in which Ambassador Christopher Stevens and State Department computer specialist Sean Smith died of smoke inhalation when the building they were in was set on fire by attackers.

Advertisement*

Map locating Benghazi. Tribune News Service 2016

The flaws are especially evident, Cooper charged, in stand-alone buildings in Tripoli, Libya, known as compound emergency structures. The buildings were intended to give diplomats safe refuge should they have to flee embassies or consulates, or if their residences on embassy compounds were to come under attack.

The buildings in Tripoli for now are unlikely to be used. U.S. Embassy operations in Libya were suspended on July 26, 2014, and the staff relocated to Malta during heavy fighting between rival militias. The embassy compound was eventually occupied by one of the militias.

Before those events, however, Cooper had argued in a May 28, 2013, analysis sent to senior diplomatic security and building officials that the compound’s emergency structures were likely to fill with toxic gases, killing those they were meant to protect. His bottom line: If fire were used as a weapon — such as fuel poured around the structures and ignited, as happened in Benghazi — they would rapidly fill with toxic gases “such that no occupants would be expected to survive.”

There is a common thread to the cause of the design flaws, Cooper wrote: “namely, the innovative technology required to design successfully both security systems required technical expertise that was beyond the capabilities of the otherwise skilled mechanical design and fire safety engineers of the [Department of State] office with official responsibility and control in the area of DOS facility design.”

Cooper had been hired at the State Department in large part because of his expertise. Before joining State, he’d specialized in applied fire-safety research for two decades at the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. He’d also spent 10 years studying the effects of nuclear weapons at Bell Telephone Laboratories.

With his contract coming up for renewal in March 2014, Cooper met in mid-2013 with State Department officials to discuss his concerns. Unsatisfied with their response, he distributed his findings to the State Department’s inspector general, the Office of Special Counsel and 11 members of Congress.

In February 2014, Cooper was summoned to a “surprise” meeting with State Department personnel officers and fired. He was required to gather his possessions and leave State Department premises immediately.

The concern about fire is nothing new. Nearly 50 years ago, the threat of fire was a factor in a June 5, 1967, attack by a mob on the then U.S. consulate in, ironically, Benghazi.

“I was at the foot of the wide marble staircase when the breakthrough occurred,” wrote an unnamed witness to that earlier assault whose account was included on page 18 in a State Department review of the 2012 attack. “Fanatical knife-carrying intruders … ran down the hall. Putting on gas masks and dropping tear gas grenades, we engaged them on the stairs with rifle butts. … We then moved into the vault, securing the steel combination door, locking in ten persons.”

The account continues: “My greatest fear, which I kept to myself, was that gasoline for the generator would be found, sloshed under the vault door and ignited. When after minutes this did not happen, our hearts sank, nonetheless, as outside smoke wafted in and we knew the building had been set afire.”

That was almost the exact scenario that led to the deaths of Stevens and Smith 45 years later.

___

(c)2016 McClatchy Washington Bureau

Visit the McClatchy Washington Bureau at www.mcclatchydc.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Advertisement