NCAA restores batting power outage

April 13, 2015

The NCAA brought the power back to college baseball.

In 2011, the NCAA implemented a new standard, Batted Ball Coefficient of Restitution, or BBCOR for bats, which regulates how much energy comes from the ball on contact.

With it, the safety of pitchers increased and stopped balls from flying out of the park, akin to Robert Redford’s character, Roy Hobbs’ final home run in the film “The Natural.”

Advertisement

Since the change, NCAA home runs, batting average and scoring average decreased each year. In 2014, teams averaged 5.08 runs per game, the lowest since 1973, one year before aluminum bats were introduced. Teams averaged 0.39 home runs per game last season, the lowest in history.

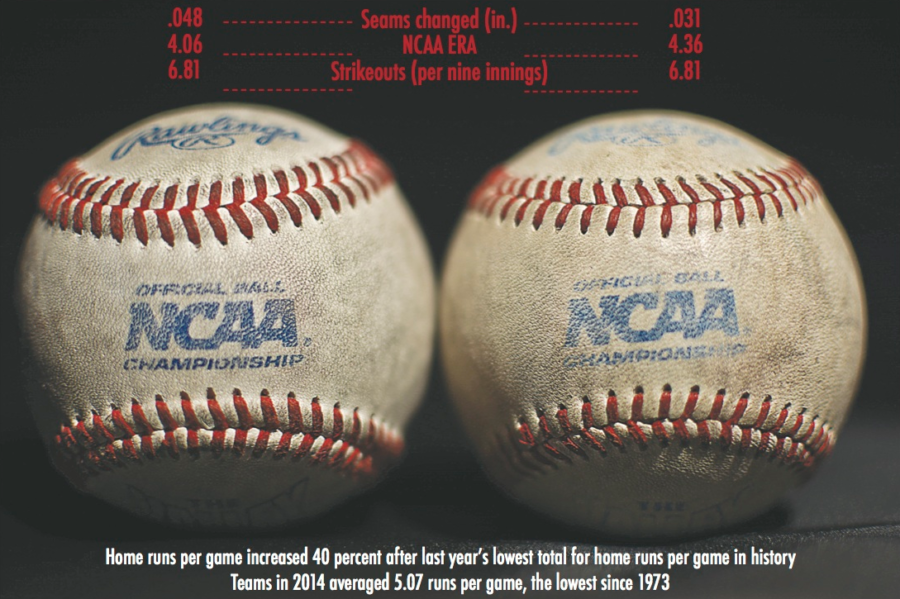

In order to bring the offense back, the NCAA lowered the laces of baseballs by 0.017 inch before this year. Now the seams are flat on the ball, similar to those used by the professionals.

As a result, home runs have increased 40 percent from last year to this point, partly because of the decrease in drag forces from the sunken seams.

Saluki senior outfielder Parker Osborne said he sees this as a good thing for the game to increase excitement.

“You know what they say — ‘Chicks dig the long ball,’” Osborne said.

Eric Chitambar, an assistant professor of physics, said the reduced drag is the reason for more home runs. He said drag is resistance of the ball’s motion because of the surrounding air molecules.

“If there was no drag and you threw a baseball, it would just sail forever,” Chitambar said. “That’s what causes the baseball to slow down and gravity pulls it down to the ground.”

Advertisement*

The new balls, developed at Washington State University Sports Science Laboratory, travel 20 feet farther off the bat than their raised counterparts because of the decreased drag.

Osborne said he has not noticed the change while throwing, but has seen more lift on balls he has hit. He increased his 2014 batting average from .250 to .274, the second best on the team.

“We’ve seen more home runs here already—not from us exactly,” Osborne said. “Some of the balls I’ve hit [this year] compared to last year have surprised myself.”

However, good news for Osborne does not mean good news for the pitching staff because SIU has given up more homers than they have hit.

The Salukis gave up 15 home runs through April 12 last year, and have allowed 21 this year through April 13. Even though there has been an increase in power nationwide, the Salukis have hit fewer dingers than this time last year: 12 to 9.

With the lowered laces, some people might think pitchers have less grip, but that has not been the case. Despite the earned-run average raising from 4.06 to 4.36 across the NCAA, the strikeout rate has gone from 6.81 to 7.66 per nine innings.

The Salukis have worsened their ERA from 3.50 to 6.13.

A pitcher does not just have to worry about drag and gravity, but also the ball’s spin.

Chitambar said the ball being pitched is similar to a plane lifting off.

For a sinker, the pitcher puts top-spin on the ball. This makes the air molecules under the ball move faster than those on top.

“If you have a differential in velocity, the spin is what is getting the molecules moving faster, then you have a difference in pressure,” he said. “You have a greater pressure above the ball, then below the ball, that’s what causes it to fall.”

Sophomore pitcher Chad Whitmer said he has noticed the change in the balls and welcomes it.

For one of Whitmer’s curveballs, air molecules are moving faster on the left side, making the ball slide to the left.

This should make the air less agitated and cause less movement, but Whitmer said his breaking balls have benefited from the change.

“With the higher seams, breaking pitches were more loopy,” Whitmer said. “With the short seams, the off-speed is sharper.”

Whitmer said his pitches are also faster with the reduced drag.

“I’ve been pretty successful with it lately, so I can’t really complain,” he said.

Both players said they have made no changes to their techniques to adjust to the ball.

Austin Miller can be reached at [email protected] or at 536-3311 ext. 269.

Advertisement