Liberia declared free of Ebola, but authorities remain cautious

May 10, 2015

Slightly more than 13 months since Liberia’s first case of Ebola, the West African nation Saturday was declared free of the deadly disease, 42 days after the burial of the last victim on March 28.

In the world’s worst outbreak since Ebola’s discovery in 1976, more people died in Liberia than any other nation, as the disease swept through densely populated neighborhoods of Monrovia, the capital.

Amid the celebration Saturday, there was a note of caution from the World Health Organization because neighbors Sierra Leone and Guinea continue to struggle with the disease.

Advertisement

“While WHO is confident that Liberia has interrupted transmission, outbreaks persist in neighboring Guinea and Sierra Leone, creating a high risk that infected people may cross into Liberia over the region’s exceptionally porous borders,” the organization said in a statement Saturday.

After the first case in Liberia was reported in late March 2014, the outbreak was at first limited and appeared to be contained. But by June, the contagious disease had hit Monrovia, the first time it had ever spread to a densely populated city.

Thousands died, and health experts feared that the disease would spin out of control, and become endemic – an awful new part of everyday life in Liberia – before the number of infections finally began to decline in October.

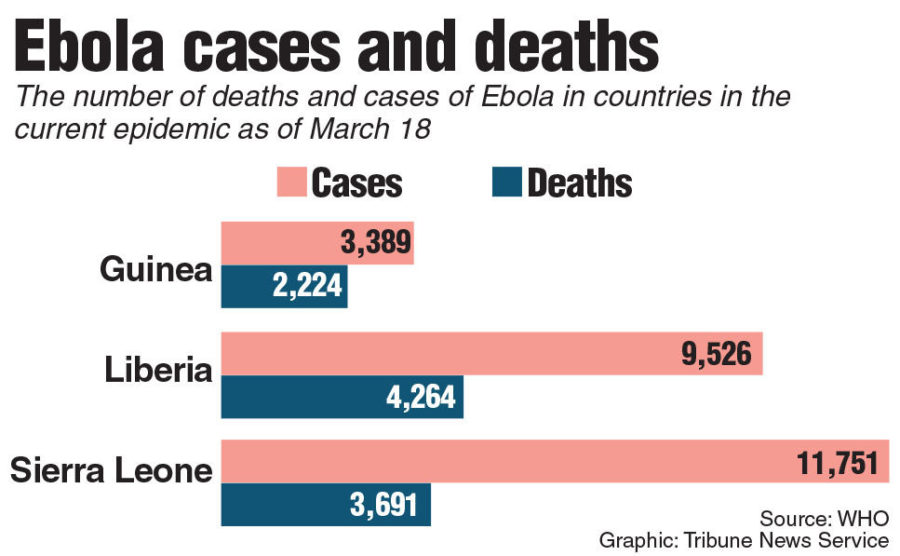

Confirmed and probable deaths from Ebola have surpassed 11,000 in West Africa, including more than 4,700 in Liberia.

In Guinea, 2,387 deaths have been attributed to Ebola, and Sierra Leone recorded more than 3,900, according to WHO figures.

The Ebola epidemic began in Guinea in December 2013, spread to Sierra Leone and then skipped across the border into Liberia.

One reason why the virus spread so rapidly was the large volume of cross-border traffic and the persistence of unsafe burial practices, with the touching of the dead an important part of the region’s culture. People traveled across borders to attend funerals and returned home with the illness, infecting family members and neighbors.

Advertisement*

Many of those who died were health workers, community nurses and faith healers, who treated people without protection, particularly in the early stages of the epidemic. In Liberia, 375 health workers were infected and 189 died. More than 860 health workers were infected in the region and more than 500 died.

The WHO said Liberia’s eradication of the virus was “a monumental achievement” in dealing with the most complex outbreak of the disease ever seen.

The incubation period for the virus is 21 days, and a country can be declared free of Ebola only after 42 days _ twice the incubation period _ have passed.

As of May 6, the total number of suspected cases during the outbreak was close to 27,000. As the disease peaked in Liberia in August and September, the number of cases was increasing rapidly, by 300 to 400 a week.

Patients often mistook their symptoms for typhoid or malaria and tragically delayed seeking treatment, infecting members of their families.

Treatment facilities were swamped with cases, and patients often died in terrible circumstances at the gates of treatment centers because there was no room inside to treat them safely.

Taxis ferrying sick passengers for treatment may also have spread the disease.

Entire families were wiped out. Some orphans were left as sole survivors in their families.

To help stop the spread of the virus, schools were closed and public gatherings were banned. Ambulances struggled to reach patients in time. In some cases community members left bodies in the streets; in others family members carried their loved ones to hospitals in wheelbarrows.

Survivors of the disease told horror stories of the conditions in treatment units, with people suffering and dying next to them, or mothers dying, leaving sick children behind. Other patients often stepped in to help when children were left alone in treatment centers.

As late as September, the world’s response was lagging disastrously, and the lack of sufficient beds in treatment units resulted in a failure to avert thousands of deaths.

“At one point, virtually no treatment beds for Ebola patients were available anywhere in the country.

“With infectious cases and corpses remaining in homes and communities, almost guaranteeing further infections, some expressed concern that the virus might become endemic in Liberia, adding another _ and especially severe _ permanent threat to health,” the World Health Organization said in its statement.

“It is a tribute to the government and people of Liberia that determination to defeat Ebola never wavered, courage never faltered. Doctors and nurses continued to treat patients, even when supplies of personal protective equipment and training in its safe use were inadequate.

“Local volunteers, who worked in treatment centers, on burial teams, or as ambulance drivers, were driven by a sense of community responsibility and patriotic duty to end Ebola and bring hope back to the country’s people,” the WHO statement said.

Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf said that for many in the country, it will take a generation for the pain and grief to heal. She referred to the slow response of the international community when she told the Associated Press that the epidemic was a “scar on the conscience of the world.”

A White House statement urged vigilance to prevent the return of the disease to Liberia.

“We must not let down our guard until the entire region reaches and stays at zero Ebola cases,” the statement said.

Advertisement