Thompson Woods’ Last Stand — Restoration the only way to save our ailing forest

December 2, 1999

When the Thompson family sold what is now Thompson Woods to SIUC in 1940, the area was a flourishing woodland dominated by oak and hickory trees and a haven for family picnics. But walk through parts of the woods today, and you’ll likely get stuck in the invasive weeds that beset a forest filled with dead and dying trees.

The restoration of the declining Thompson Woods is an ongoing preservation battle, and a loss could turn the once vibrant forest into nothing more than an exotic weed jungle. Or possibly, a parking lot.

“I’ve heard people talk about paving the woods over and turning it into a parking lot,” said Paul Roth, an SIUC professor of forestry. “The University is big on parking lots.”

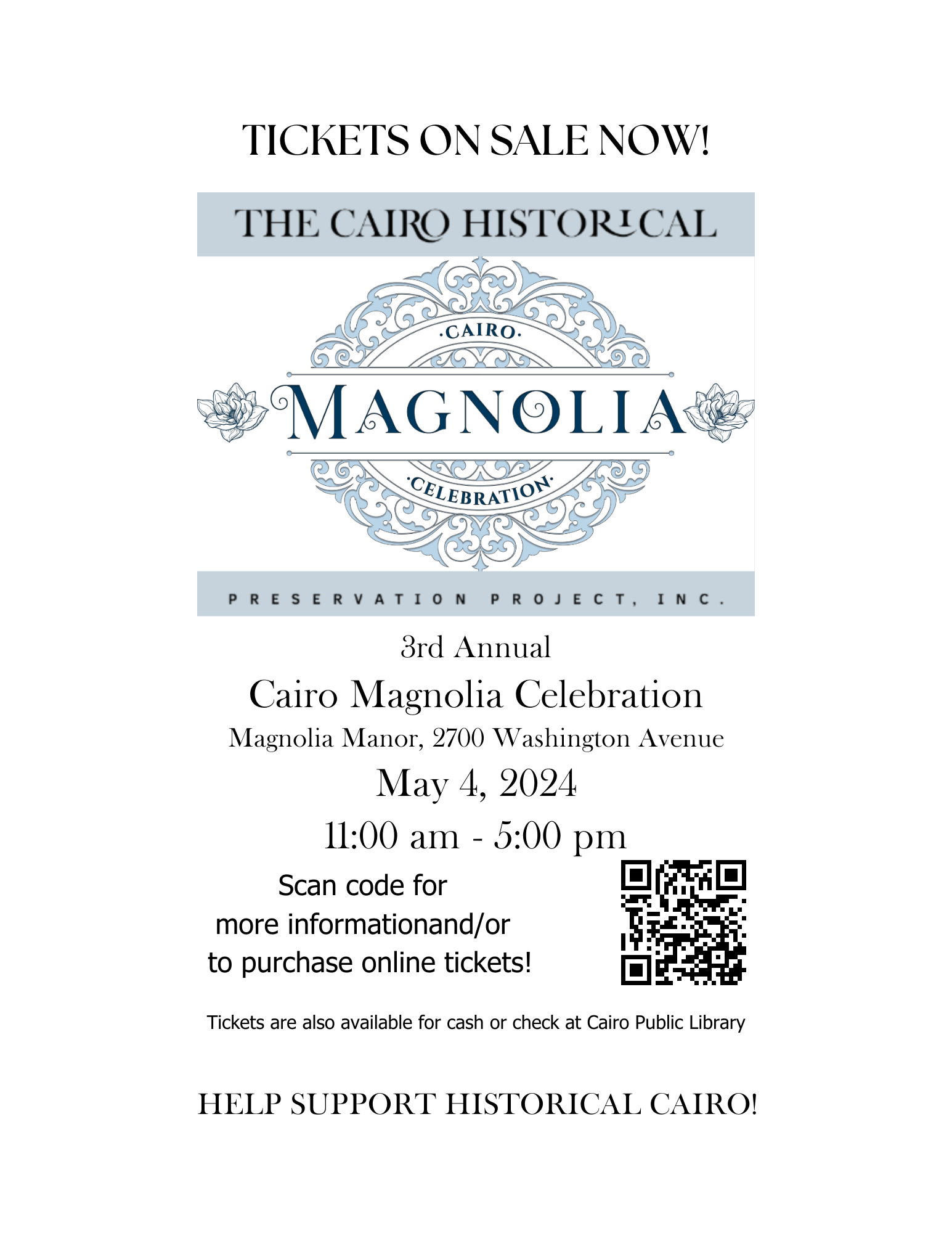

Advertisement

While this option may seem like a radical notion, something needs to be done in the near future if the woods continues to decline. Most of the black oak trees, the dominant tree species in the woods, have reached the end of their life cycles and are about 125 to 150 years old. Once a black oak reaches this age, it is near death.

“Right now they’re dropping very fast,” Roth said.

Also, vine species and weeds are winning the competition for sunlight, choking out developing oak seedlings. The shade-tolerant beech and maple trees are not a dominant part of the woods’ natural state as an oak and hickory forest, but that is exactly where the forest is headed.

“The comment you get from people about Thompson Woods is always the same,” Roth said. “They say, ‘It used to be a nice woods, but…'”

That “but” is a problem the University must consider before the unwanted make-over is complete. For many people in the SIUC community, including forestry professor James Zaczek, what to do about Thompson Woods remains complicated.

“It’s a tough question,” Zaczek said, “and it’s not an easy answer.”

How the forest faltered

Advertisement*

As a forest stand, Thompson Woods is now too small and fragmented to survive as a functioning ecosystem without the aid of human intervention. But at one time, the woods was able to develop on its own.

After a clear-cut in the late 1840s, timber from the forest was used for railroad ties, fuel for homes and businesses, and local building construction in Carbondale when the city was founded in 1854. After the woods returned to its original state, the area became a popular picnic location.

Duane Schroeder, a former grounds-keeping foreman, played in the woods as a child prior to its sale and has watched its degradation throughout the years.

“You used to be able to stand on one side of the woods and watch the sun set right through it,” Schroeder said. “It was really a beautiful spot.”

The woods was a place the whole town was welcome to enjoy. The Thompsons never fenced in the land, allowing people to come as they pleased. The family owned 85 acres, which now includes the woods and Thompson Lake, and sold most of it to the state for $6,250 in 1940. Now about 10 acres sectioned in the center of campus, Thompson Woods originally covered about 15 acres.

Years passed and time took its toll on the wood as several unforeseen problems in the past two decades led to its gradual decline.

In June and July of 1980, a strong wind storm knocked over numerous large trees, destroying much of the canopy. The open canopy allowed excess sunlight to strike the forest floor, resulting in a surge of weed species.

As they were not closely monitored, non-native vine species such as creeping euonymus and Japanese honeysuckle invaded. The lack of fire to the site has also allowed for the exotics to flourish. Oak forests need periodical fires for the regeneration of new stands.

The seedlings and smaller trees are facing competition from the vines, and shade-tolerant beech and maple trees. Because the vines and shrubs have choked out the oak seedlings, there are not many trees to replace the dying ones. To compound the problem, the squirrel and mice populations are rapidly devouring available acorns, rendering the woods unable to regenerate by themselves.

“One thing people don’t realize is there’s so many mice and squirrels, the acorns don’t make it to germination,” Zaczek said. “The populations are so immense.”

The thing that does grow, though, is the amount of trash and cigarette butts people throw into the woods. Carbondale Fire Department Capt. Gary Heern said a discarded cigarette was likely the reason for a brush fire Nov. 18 that burned about a 50-foot radius on the north side of the woods behind Morris Library.

“This is supposed to be the environmentally conscious generation, but Thompson Woods is littered all the time,” Roth said.

What’s more, the hundreds of students who cross through the woods daily create user paths off the paved trails, which compact the soil and expose the trees’ roots. If they are trampled enough the trees are exposed to infection.

“Thompson Woods is supposedly one of the key things that alumni remember about the campus,” Zaczek said. “But the only constant is change, and unless someone’s willing to actively manage it, it’s going to change.”

And, Zaczek said, the change could herald a tidy weed patch.

Who will save our woods?

Thompson Woods lies at the University’s heart, and is an aesthetically pleasing walk for students using it as an artery to classes. But now that the forest is faltering, most agree the time has come for major reconstructive surgery.

Since 1995, a team of workers has battled to solve the dilemma. The Thompson Woods Management Committee, led by plant biology professor Philip Robertson, formed to help restore the forest to its original state.

Adopt-A-Patch uses separate groups, and each group maintains a patch of woods utilizing work days to clear the weeds and vines, and plant small oaks, but the number of student groups actively involved has dwindled as much as the woods itself.

While about 10 groups originally agreed to the proposal, the number of groups maintaining the patches is now about half. Some patches have received help and others have not.

Terry Miller, a senior in plant biology and Adopt-A-Patch volunteer, said students can do only so much, and without University aid, the woods will experience a demise from a hardwood stand to a weed jungle. Miller suggests hiring students to spray herbicides and manually clear the exotics.

“To really accomplish what needs to be done, the University needs to commit to a more direct involvement in the woods,” Miller said. “The bottom line is that with the amount of exotics, a more hands-on approach with a commitment of funds needs to occur.”

While SIUC’s groundskeepers have watered and kept some weeds in check during the summer, the University has not donated any financial assistance.

When the woods was sold, there was a much-debated “gentleman’s agreement” that the University maintain the woods in its natural state of a hardwood oak and hickory forest. When the University cut a one-fifth mile area on the west side of Campus Lake in 1987, the clearing created an uproar from people who claim the woods should not be disturbed from its original state.

But the agreement is not included in the documentation, meaning the University can either maintain the woods in a natural state or let the woods wither into oblivion.

“Ultimately, it’s part of the University landscape, and it would be in their own best interest to spend more time on it.” Zaczek said. “But it does take money, and the University only has so much money.”

The Grounds Department, which functions as part of the Physical Plant, has lost numerous workers and funding. Between fiscal year 1991 and fiscal year 1998, the Physical Plant’s budget has decreased by $2.3 million, despite the increase in maintenance needs. Most of the University’s maintenance funds are going toward deferred maintenance, which are projects like asbestos abatement and building remodeling.

But some professors including Zaczek are not convinced the woods should be overlooked in the process.

“Maybe the woods needs some deferred maintenance,” Zaczek said.

While funds are diverted to deferred maintenance projects, Thompson Woods awaits funds that may never come. Instead, the University has relied on the efforts of others, including donations from alumni and emeritus professors.

Jim Fralish, a retired associate professor of forestry, donated more than $12,000 to the rejuvenation project.

“The woods have a long way to go,” Fralish said. “It will look worse before it looks better.”

The Fate of the Forest

Robertson said there are a myriad of ideas and suggestions for what Thompson Woods needs, but a finalized agreement is a necessity for the woods to become what it once was. That said, help may be on the way.

Vice Chancellor for Administrative Affairs Glenn Poshard is working with a 12-member group of faculty and staff on a Land Use Plan that will address what to do about the woods, according to Robertson, who is a member of the team. But Robertson said there have been no definitive plans for the woods.

Most agree that the use of herbicide and fire to eradicate the exotics is needed. Other suggestions have been asking alumni for financial contributions, continual planting and getting funding from the University. The honeysuckle would need to be cleared on a yearly basis, and a group would be needed to monitor and maintain the woods.

“The only way to get it done is spend a lot of effort and money on the woods,” Zaczek said. “I think the University would be justified in spending some money on it. It’s the same thing as spending money on lab space it’s an outside lab.”

The woods’ educational purposes are vast. Forestry, plant biology and other SIUC professors use the woods to educate on ecosystem use, for plant and tree identification and to study the rehabilitation of forests.

Zaczek, who obtained his SIUC forestry undergraduate in 1980 and a forestry master’s in 1982, said while it has declined from the time he attended school, he does use the woods for educational purposes.

“It’s got some good examples of what not to do with a woods,” Zaczek said.

For now, the battle continues as Robertson plans to plant more small oak trees Saturday. He hopes that once restored, the forest will contain mostly black oak and hickory with wildflowers replacing the weeds.

Roth said there is a lot of work ahead for the woods, but the effort will pay off for those who appreciate the natural beauty of a woods rather than a parking lot.

“We don’t want another one of the concrete-asphalt jungle campuses,” Roth said. “Our concern is to protect and manage it so that students 20, 40 and 60 years from now still have a nice woods.”

Advertisement