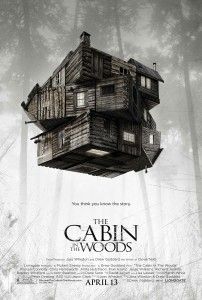

‘Cabin’ offers good moments, but no escape from bad horror

April 15, 2012

Lest we ever forget that most horror films are highly conventional, we now have “The Cabin in the Woods” to mercilessly drill the point home.

The latest offering from genre maven Joss Whedon (who produced and co-wrote) and up-and-comer Drew Goddard proposes to both be a horror film and a film about horror films.

It’s kind of like “Scream””on steroids.

Advertisement

As one could probably guess from the knowingly straight-forward title, the film follows a group of extremely good-looking college students as they go on a trip to a mysterious cabin high in the mountains and proceed to be killed one-by-one by a family of redneck zombies.

Where “Cabin” diverges from other horror films is its subplot (or is it the main plot?) about a secret agency carefully controlling the film’s events from a high-tech underground base. I won’t ruin the big reveal of its motivations, but most viewers will probably have it more or less figured out by the 30-minute mark.

It doesn’t take long to realize that essentially everything that happens in the movie is either deliberately conventional or deliberately unconventional. Either way, it’s played for laughs, and the technicians who pull the strings, played wonderfully by Richard Jenkins and Bradley Whitford, become sort of meta-filmmakers within the film.

I guess it’s one of those “high-concepts” you hear about.

But there’s no doubt there are plenty of fun moments in the film.

A scene when the college students discover a secret room filled with conventional monster-summoning objects (a Hellraiser-esque trinket, a creepy wind-up ballerina and, among others, a century-old diary that reveals dark family secrets) is one highlight.

Also great is a brief send-up of Japanese horror films, an amusing (though quite violent) deflation of Chris Hemsworth’s alpha-male character’s heroism and nearly anything involving Jenkins and Whitford.

Advertisement*

However, all the self-referencing of the film is ultimately a little unsatisfying.

The whole film-as-criticism thing has been around since at least the French New Wave, and that was 50 years ago.

It’s fitting that the director’s name should be Goddard, calling to mind one Jean-Luc, and based on Whedon’s comments on the film, it sounds like “Cabin” was meant to be a sort of corrective influence on a genre the filmmakers saw as having stagnated.

So it’s kind of like the “Breathless” of slasher films.

Kind of.

This is all fine and dandy, and I would not argue at all with Whedon on the dire state of horror film, though I can’t help but wonder why not just make a really, really good, earnest horror film?

Why can’t these talented filmmakers just make a — dare I say — innocent genre movie?

Somewhere along the lines we seem to have suffered a sort of Fall, and in this postlapsarian, super-self-aware world, Whedon and Goddard can’t make a genre film without winking at the audience. It’s as if they’re afraid of getting caught with their pants down, enjoying themselves a little too much with their little genre movie.

“The Cabin in the Woods” is the apotheosis of reflexive genre filmmaking. Unfortunately it doesn’t really tell us anything most people probably didn’t already know about horror films, and though it’s fun, it doesn’t function very well as an actual horror film.

While its meta-ness by no means dooms “Cabin,” it is a problem when the film becomes slave to it.

The kids are all cookie-cutter characters because they’re manipulated to be so. The zombies are completely indistinguishable from any other movie zombie because they are, quite literally, stock monsters.

If there’s any way that the meta-subplot really helps, it’s that it gives agency to all the annoying contrivances of the genre, and with Jenkins and Whitford behind the controls, we now have someone other than the writers to blame for the bone-headedness of the plot.

The characters do painfully stupid things because they’re drugged, and what would be a pretty easy, straightforward escape is doomed because there’s someone in an office pushing a button to blow up the road.

Still, I have to ask: Why not just refrain from those things altogether?

Where the film really takes off is its final act, when Whedon and Goddard throw caution, and criticism, to the wind and let all hell break loose.

It’s just a shame they didn’t make the rest of the film in the same spirit.

Advertisement