A study on the local Giant Cane Bamboo done by two researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale looks into how the species interacts with itself and its environment via wildlife, soil, water, and other factors of nature and why it’s so important to the community and it’s history.

“The study that you saw is like a side project that we tried to look at the correlation between the overstory, like forest cover, and how the cane is, like, within terms of how dense it is, how dense they are, how tall and how big the patch is,” said Thanchira “M.J.” Suriyamongkol, the graduate student leading the study said.

Advertisement

examines a patch of Giant Cane bamboo growing inside Thompson Woods

on campus Aug. 20, 2024 in Carbondale, Illinois.

lgibbs@dailyegyptian.com (Lylee Gibbs )

Suriyamongkol works along with forestry professor Jim Zaczek who’s done studies on the Cane with other professors and students in the past.

“That kind of come[s] from, like, my dissertation study that we look at,” Suriyamongkol said. “We look at the occupancy, or how, like, [the] wildlife community utilize the cane in general, of like, the remnant that we have left in the area.”

The scientific name for it is Arundinaria gigantea, also known as a river cane and giant river cane.

Advertisement*

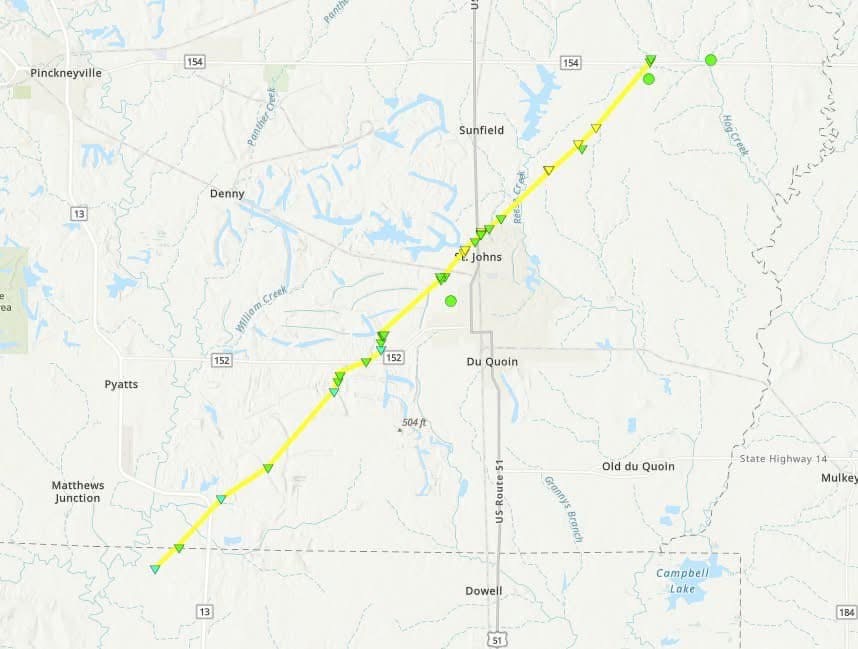

The Cane Suriyamongkol looked at for research were located around the Trail of Tears and Cypress Creek area with around 30 patches of Giant Cane.

“The wildlife portion of it, we conduct a study in the summer, from April to the end of August, or like September, and we have been doing that for the past three years,” Suriyamongkol said. “This is the last year we’re doing that.”

Suriyamongkol and Zaczek would regularly monitor what species integrated with the cane, seeing birds, tree frogs and reptiles, raccoons and bobcats.

Audio logs were used to listen to animal calls and cameras to monitor how and when animals interacted with the cane patches.

“It’s in the grass family, Poaceae, so it is a grass… I would consider it a woody grass, because it forms these thickets when there’s plenty of light and exposure and disturbances and things like that,” Zaczek said.

Historical documents show large patches of the cane in the area along river bottoms and alluvial floodplains around the 19th century, Zaczek said.

With it being an important cultural resource for Indigenous history in the community, there’s a lot of interest in restoration of the plant.

“Because of the cultural importance for Native American, they used it for building, they used it for Arrow shafts. What baskets? And, you know, it was an important material, and there’s just not much of that left,” Zaczek said.

Old reports show that Native Americans were regularly using the cane, said Suriyamongkoln. As Europeans settlers came into the community they cleared the wetlands and cleared space for agriculture which could’ve had an impact on spread and growth.

Cane benefits from periodic burning to restore it similar to prairie grass, said Zaczeck. Recommended to do it sparsely every seven to ten years, it can help the can populate and knock back woods and trees.

A study done in the early 2000s by Zaczeck, Sara Baer and David Dalzatto tested the impact of fertilization and a prescribed direct fire on mixture to promote growth and spread of the cane in a four-year period.

Results from the study showed that fertilization on already established cane can decrease in culm (stem) morality and the periodic burning can increase the density and spread of the cane, showing good stimulation of growth.

Another study done by Zaczek and Baer along with other forestry professors found that the giant cane’s rhizomes established in the greenhouse or planted in the fields can be used to stimulate growth in canebrakes that could lead to wide-scale restoration.

“So over the years, we’ve had a lot of students working on different methods of propagating it, and then once we figured out a good method… of propagating it, we were looking at, how do we plant it out in the fields,” Zaczek said.

Zaczek said over the years cane has been planted in Thompson Woods as a part of past student and professor studies

“It grows with underground rhizomes…which are underground stems, essentially,” Zaczek said. “There’s a little patch of light that shines through parts of the day. So this is a better spot for it to grow.”

Though the Giant Cane isn’t as populated in the area as it was in the past, studies have shown a positive rate in growth that has in return benefited the environment around it.

“ If it opens up and you get plenty of light, and they get very dense where you can, barely even walk through it,” Zaczek said. “It’s all about how many resources they have, the heaven of light, water and nutrients they can really grow well.”

To stay up to date on all your southern Illinois news, be sure to follow The Daily Egyptian on Facebook and @dailyegyptian on X [formerly known as Twitter].

Jamilah Lewis can be reached at jlewis@dailyegyptian.com. To stay up to date with all your southern Illinois news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement