Coming out of a summer that has seen temperature records smashed, forecasters are predicting a record-setting winter as well, largely because of a weather phenomenon known as El Nino and its interaction with wide scale climate change.

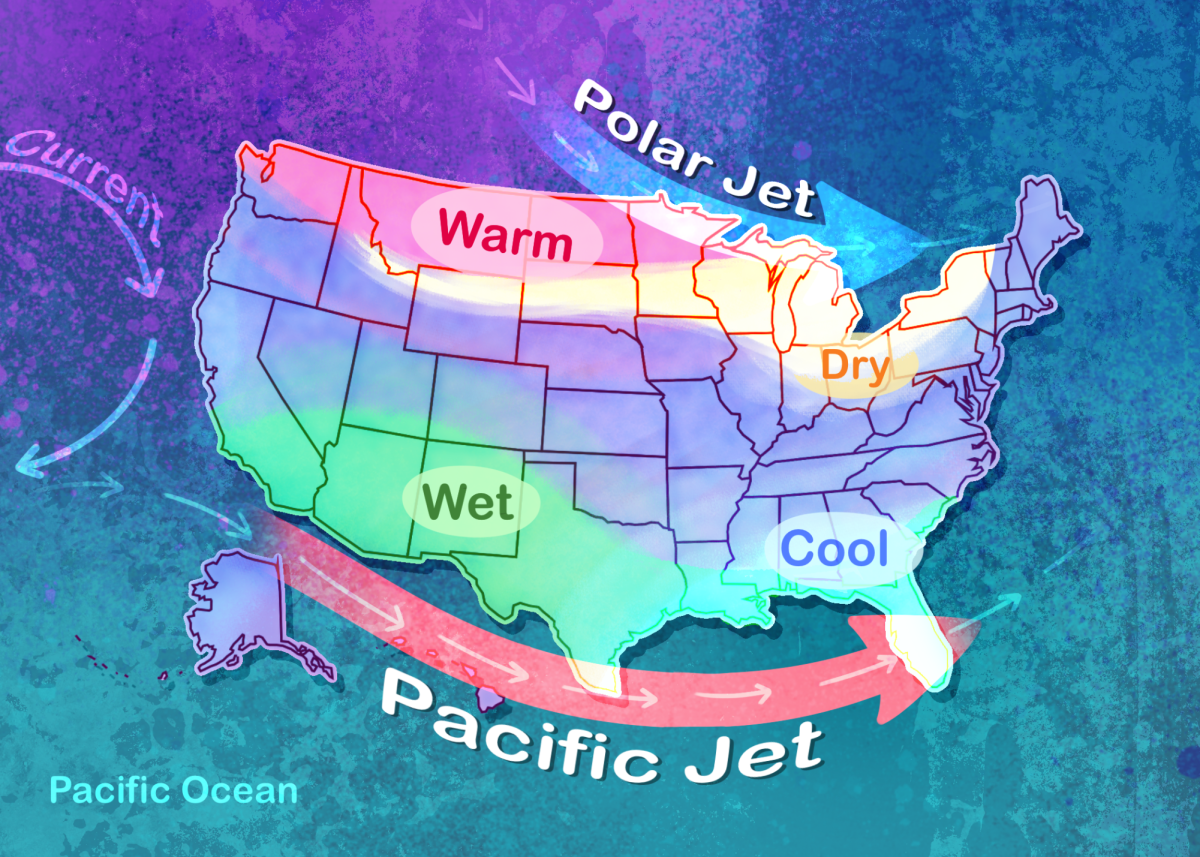

For Illinois, that means a warmer, drier winter than usual.

The El Niño weather pattern is rising much earlier in the year than usual, bringing warm, dry air from the north and relatively cool, wet air from the south, according to an article by Peoria-based CBS affiliate WMDB. The Climate Prediction Center expects it to last into early 2024, bringing heat waves and dry, wildfire-prone conditions to the northern half of North America.

Advertisement

“If you think of the area primarily off the west coast of South America, during an El Niño, that part of the ocean surface gets very warm relative to the average,” said Justin Schoof, professor of geography and environmental resources at Southern Illinois University (SIU).

According to Schoof, the warming of the water off the coast of South America has a global effect, warming the entirety of the planet’s lower atmosphere. During the reciprocal event, known as La Niña, the water is cooler than what would normally be expected.

“So having all of that warm water there, for example, means that the ocean is expelling more heat to the atmosphere, which means the world is generally warmer during an El Niño,” Schoof said.

El Niño is typically characterized as a winter phenomenon, taking its name from the Christmastime around which it usually happens, relating it to the “boy child.”

“So what that means is, knowing that 2023 already has an El Niño emerging, I might venture to guess that this would be a record setting year,” Schoof said.

He attributes some of the record setting heat we’ve been experiencing to the phenomenon, though the correlation is not always as indicative of causation as we might believe at first glance.

“So we know that during El Niño’s, the atmosphere is generally warmer, which means it’s likely to play some role in many of the events that happen, but things get a bit sticky here,” he said. “So if our trend is going upward over time, but there’s a lot of natural variability primarily from El Niño and La Niña, it gives me pause.”

Advertisement*

Schoof said the setting of individual temperature or weather records may come as a resultant combination of these oscillating weather patterns but, more importantly, due to the climbing of temperatures over time.

“That’s a very important nuance. We can always point to any extreme event as having a number of causes, so if we would have had an El Niño this strong 20 years ago, it wouldn’t be a record like today. It’s only a record due to the underlying trend,” he said.

While these patterns definitely have an effect on weather, Schoof said not all the extreme phenomena we are currently seeing across the U.S. can be solely attributed to it.

“We normally expect fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic with El Niño, because it actually increases the wind shear, so storms that form in the Atlantic might get ripped apart before they have the ability to mature,” Schoof said. “But during a La Niña, you have a lower than average level of shear, so the storms are able to have a bit more time to get organized before shear comes along and basically breaks them apart.”

The National Oceanic and Aerospace Administration (NOAA) has a scale for defining hurricanes, from tropical depressions to tropical storms and finally to fully-fledged hurricanes as the winds within the storms increase. But what these storms have in common is their association as low-pressure, organized thunderstorms with no front separating its parts.

“Hurricanes are powerhouse weather events that suck heat from tropical waters to fuel their fury,” NOAA said in an article from August. “As this weather system moves across the tropics, warm ocean air rises into the storm, forming an area of low pressure underneath, causing more air to rush in. The air rises and cools, forming thunderstorms while, up in the clouds, water condenses and forms droplets, releasing even more heat to power the storm.”

NOAA said these storms continue to build as they suck up moisture-laden air until they are able to make landfall, at which point they are no longer able to draw energy from the ocean and begin to dissipate over days or sometimes weeks.

“Hurricanes can affect us here, not as hurricanes but as tropical remnants,” Schoof said. “Back in 2008, Hurricane Ike actually knocked down trees in Illinois. It wasn’t a hurricane when it did hit us, but it was a very strong wind system.”

Schoof said one of the important things to remember regarding the current and persistent extreme weather we’ve been seeing is the unpredictability of the effects of climate change on the system as a whole.

“For example, the large heatwave we just had, and the large fires in Canada earlier in the summer, those are both caused by very large, persistent high pressure systems,” he said. “So we know the earth is warmer than it used to be, and that with this much climate change in the system, it’s likely that it has some role. But as for how it directly affects the formation and persistence of these systems, the answer is we don’t really know very well.”

Schoof said our environment can change in subtle ways from numerically small deviations from what we expect from “normal” climate conditions. These changes can affect varying parts of the global climate system in unpredictable ways and can, and often are, exacerbated by humans.

“The Maui fires are a good case to discuss because they had issues where there’s now a lawsuit against the utility for not turning off the power when they knew there were 80 mph winds and live electric lines, which are now thought to have been the trigger for that fire. So is that a climate change issue?”

Schoof said recent economic downturns have led to sugar plantations, one of the largest exports from Hawaii, closing down and being replaced by native grasses and shrubbery reclaiming the land, which easily caught fire when exposed to the large blazes that had begun to consume the island.

“It’s easy to want to look and say, ‘Oh, climate change.’ But it’s usually way more complicated than that because it involves people, and people make things way more complicated,” Schoof said. “So nature definitely plays a role there, but there’s clearly also a climate change role, and the difficulty comes to figuring out the size of each.”

Staff reporter William Box can be reached at [email protected] or on Twitter at @William17455137. To stay up to date with all your southern Illinois news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement