George McGovern dies, had ties to SIU

October 22, 2012

A historical American figure who passed away Sunday had some experiences at SIU.

George McGovern, a proud liberal who argued fervently against the Vietnam War as a Democratic senator from South Dakota and three-time candidate for president, died at 5:15 a.m. Sunday at a Sioux Falls hospice, family spokesman Steve Hildebrand told The Associated Press. He was 90 years old.

McGovern, who ran against Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election, attended the university in 1943 for Army Air Force Training when it was still Southern Illinois Normal University, said Matt Baughman, associate director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute.

Advertisement

Although Baughman said McGovern lost by a landslide, the single Illinois county for his presidential bid was Jackson County.

Sixty years after attending the university, McGovern returned to speak at the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute. Although he discussed his presidential election experience, he also spoke about his naming as the first United Nations Global Ambassador on Hunger.

“He was an interesting man, and he gave a lot to the country both as an elected official,” Baughman said. “After that, he gave a lot to fighting hunger and helping people worldwide that were in need of food. It was his passion.”

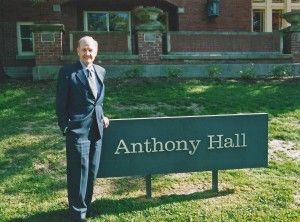

McGovern’s attendance at the university for flight training was about four to five months long, Baughman said. Although his time at SIU was short, Baughman said McGovern recalled it as memorable. He said cadets had just begun to reside in Anthony Hall, which was previously a women’s residence hall, when McGovern attended the aviation program.

“McGovern joked that because it was a woman’s dorm and he spent four months in it, it was the happiest time of his life,” Baughman said.

Another candid moment Baughman said he shared with McGovern involved his visit to SIU in the ’70s. Baughman said McGovern’s lodging was arranged at SIU’s Stone Center, which is named after Clem Stone, when the university invited him to speak. Stone was a leading financial donor to Nixon’s campaign during the 1972 presidential election, Baughman said.

“(McGovern) said, ‘Well … now I can’t say that Clem Stone never gave me anything,” he said.

Advertisement*

Baughman said McGovern also credited SIU for the experience it provided him in flight training.

“That training saved our lives many times over,” McGovern said in an article published in Southern Exposure, a former campus news publication. “I thanked God for that trainer who knew what was ahead of us. I’ll be indebted to that instructor for the rest of my life.”

George Stanley McGovern was born on July 19, 1922, in the small farm town of Avon, S.D., the son of a Methodist pastor. He was raised in Mitchell, shy and quiet until he found his niche and was recruited for the high school debate team. He enrolled at Dakota Wesleyan University in his hometown and, already a private pilot, volunteered for the Army Air Force soon after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

He married his wife, Eleanor Stegeberg, and arrived in Italy the next year, which would be his base for the 35 missions he flew in the B-24 Liberator christened the “Dakota Queen” after his new bride.

McGovern’s plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire that disabled one engine and set fire to another in a December 1944 bombing raid on the Czech city of Pilsen. He nursed the B-24 back to a British airfield on an island in the Adriatic Sea, which earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross. His plane was hit several times on his final mission, but he managed to get it back safely — one of the actions for which he received the Air Medal.

McGovern returned to Mitchell, earned his master’s and doctoral degrees, taught history and government at Dakota Wesleyan and switched from his family’s Republican roots to the Democratic Party.

“I think it was my study of history that convinced me that the Democratic Party was more on the side of the average American,” he said.

McGovern, who had gotten into Democratic politics as a campaign volunteer, left teaching in 1953 to become executive secretary of the South Dakota Democratic Party. Three years later, he won an upset election to the House; he served two terms and left to run for Senate.

President John F. Kennedy named McGovern head of the Food for Peace program, which sends U.S. commodities to deprived areas around the world. He made a second Senate bid in 1962 and won by just 597 votes. He was the first Democrat elected to the U.S. Senate from South Dakota since 1930.

President Barack Obama remembered McGovern in a statement Sunday as “a statesman of great conscience and conviction.”

“He signed up to fight in World War II and became a decorated bomber pilot over the battlefields of Europe,” the president said. “When the people of South Dakota sent him to Washington, this hero of war became a champion for peace. And after his career in Congress, he became a leading voice in the fight against hunger.”

McGovern first sought the Democratic presidential nomination late in the 1968 campaign but lost, saying he would take up the cause of the assassinated Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. The following year, McGovern led a Democratic Party reform commission that took power previously held by party leaders and bosses at the national conventions and gave it to voters instead. The result was the system of presidential primary elections and caucuses that now selects the Democratic and Republican presidential nominees.

In 1972, McGovern was the first candidate to gain a nominating majority in the primaries before the convention.

The campaign limped into the fall on a platform advocating withdrawal from Vietnam in exchange for the release of POWs, cutting defense spending by a third and establishing an income floor for all Americans. McGovern had dropped an early proposal to give every American $1,000 a year, but the Republicans continued to ridicule it as “the demogrant.” They painted McGovern as an extreme leftist and Democrats as the party of “amnesty, abortion and acid.”

He’d had enough when a young man at the airport fence in Battle Creek, Mich., taunted that Nixon would clobber him. McGovern leaned in and said quietly: “I’ve got a secret for you. Kiss my ass.” A conservative Senate colleague later told McGovern it was his best line of the campaign.

McGovern once joked that he had wanted to run for president in the worst way — and that he had done so.

It was a campaign in 1972 dishonored by Watergate, a scandal that fully unfurled too late to knock Republican President Richard M. Nixon from his place as a commanding favorite for re-election. The South Dakota senator tried to make an issue out of the bungled attempt to wiretap the offices of the Democratic National Committee, calling Nixon the most corrupt president in history.

But the Democrat could not escape the embarrassing missteps of his own campaign. The most torturous was the selection of Missouri Sen. Thomas F. Eagleton as the vice presidential nominee and, 18 days later, following the disclosure that Eagleton had undergone electroshock therapy for depression, the decision to drop him from the ticket despite having pledged to back him “1,000 percent.”

It was at once the most memorable and the most damaging line of his campaign, and called “possibly the most single damaging faux pas ever made by a presidential candidate” by the late political writer Theodore H. White.

McGovern’s campaign, nevertheless, left a lasting imprint on American politics. Determined not to make the same mistake, presidential nominees have since interviewed and intensely investigated their choices for vice president. Former President Bill Clinton got his start in politics when he signed on as a campaign worker for McGovern in 1972 and is among the legion of Democrats who credit him with inspiring them to pursue public service.

“I believe no other presidential candidate ever has had such an enduring impact in defeat,” Clinton said in 2006 at the dedication of McGovern’s library in Mitchell, S.D. “Senator, the fires you lit then still burn in countless hearts.”

Defeated by Nixon, McGovern returned to the Senate and pressed there to end the Vietnam War while championing agriculture, anti-hunger and food stamp programs in the United States and food programs abroad.

After his career in office ended, McGovern served as U.S. ambassador to the Rome-based United Nation’s food agencies from 1998 to 2001 and spent his later years working to feed needy children around the world. He and former Republican Sen. Bob Dole collaborated to create an international food for education and child nutrition program, for which they shared the 2008 World Food Prize.

Former President Bill Clinton and his wife, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, said in a statement Sunday that while McGovern was “a tireless advocate for human rights and dignity,” his greatest passion was helping feed the hungry.

McGovern’s opposition to armed conflict remained a constant long after he retired. One of McGovern’s 10 books was 2006’s “Out of Iraq: A Practical Plan for Withdrawal Now,” which he wrote with William R. Polk.

George and Eleanor McGovern returned in early 2002 to Mitchell, where they helped raise money for a library bearing their names. Eleanor McGovern died there in 2007 at age 85; they had been married 64 years, and had four daughters and a son.

“I don’t know what kind of president I would have been, but Eleanor would have been a great first lady,” he said after his wife’s death in 2007.

Advertisement