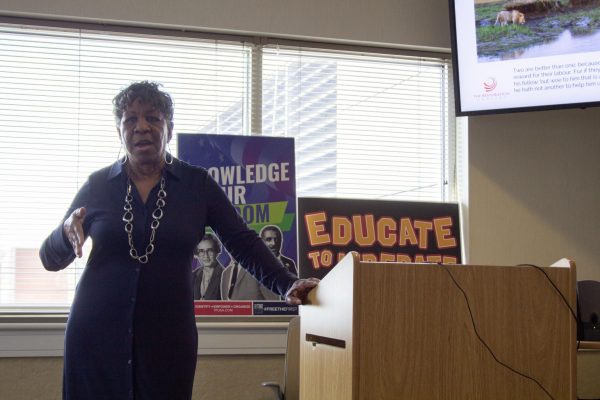

Paul Simon Institute Hosts Author and Diplomat Elizabeth Shackelford

This past week, former U.S. diplomat Elizabeth Shackelford sat down for a conversation with John Shaw of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute as part of the Institute’s Understanding Our New World series. Together they discussed her experiences in the field and in the State Department, as well as her book reflecting on those experiences, The Dissent Channel.

Born in Mississippi, Shackelford obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Duke University and a Juris Doctorate from the University of Pittsburgh. She served in various capacities working at Booz Allen Hamilton and at the law firm of Covington & Burling before going on to work for the United States State Department.

Shackelford first spoke about what inspired her to work in international studies, and her first experiences in pursuing that goal. “I knew at a pretty young age that I wanted to do something involving justice and law,” said Shackelford during her conversation with Director Shaw. “I did a study abroad in South Africa [and] I was fascinated by apartheid history and how it might mirror my own home state’s background. That set me on a path to want to do something more international.”

Advertisement

In her role at the State Department, Shackelford worked as a Foreign Service Officer in Somalia, Kenya, Poland and South Sudan. In South Sudan, Shackelford served as a Human Rights Representative, where she helped organize the evacuation of US citizens and associates after the outbreak of the South Sudanese Civil War in 2013. She would later be awarded the Barbara Watson Award for Consular Excellence, the Department’s highest honor, for her work there.

It was this last crucial deployment that Shackelford discussed with the Paul Simon Institute. “I had completely bought into the idea that the United States Government was a force for good in the world, and that I could be part of that,” said Shackelford while reflecting about her optimism for her work. “It didn’t take long to recognize when I got South Sudan, that this is not how this story is going to play out.”

The Republic of South Sudan was born out of a 2011 referendum held by the government of Sudan to decide whether to grant the region independence. A reported 98.8% result in favor of independence meant that South Sudan would be recognized as a sovereign nation, taking with it nearly 75% of Sudan’s valuable oil supply.

While the transition was celebrated by governments around the world, and especially by the Obama administration, conflict began almost immediately. Apart from internal struggles, which included the infamous Joseph Krony’s “Lord’s Resistance Army”, the new South Sudanese government found itself immediately beset by intense foreign aggression. It was with these threats in mind that the U.S. government began to push its influence into South Sudan.

“Once I was on the ground, I began to see that the story and the narrative that we were telling about South Sudan in Washington D.C. was very different from reality,” said Shackelford. “There was still a level of buying into this being a success, [yet] it became very evident to me early on that we were turning a blind eye to some really horrific behaviour by the [South Sudanese] government.”

In 2013, the President of South Sudan accused members of his government of attempting a coup, leading to an almost immediate outbreak of hostilities. By the end of the year the country had plunged into civil war. Despite the closer involvement of the United Nations, which had established a peacekeeping force in the country in 2011, the violence only escalated.

A tenuous peace deal was reached in 2020, but only after the deaths of some 400,000 people, and the displacement of millions of others.

Advertisement*

“So much about diplomacy is about relationships, and that works in good ways and in bad ways,” said Shackelford when discussing the problems she noticed with the State Department. “But there’s this inability to use those relationships to push back harder. It created a learned behaviour where we’re going to shake our finger at human rights abuses, but we’re not going to do anything about it, and we’re going to continue to support the government in power.”

Shackelford’s growing disillusionment with US diplomacy, heightened by changes in government policy she saw under the Trump administration, resulted in her submitting a letter of resignation to then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in 2017.

“I remained very frustrated at watching our policies there [in South Sudan] continue on the same path of supporting the government,” said Shackelford when asked about her decision to resign from the State Department. “I thought about it [resignation] for months, and I woke up one day and felt that I could no longer be certain that I was doing more good than harm.”

The resignation letter Shackelford penned would turn out to be a stinging criticism of both U.S. foreign policy in general, and U.S. foreign policy under Trump. It would be featured on multiple national news outlets, foreign policy journals, and popular debate shows.

“It was unexpected”, said Shackelford of the response her letter received. “But it gave me a sense that Americans care about what happens in the State Department.”

Shackelford’s book on her experiences, The Dissent Channel, has received multiple favorable reviews and awards. It is recommended to anyone interested in international studies, U.S. foreign policy, or nonfictional tales of adventure. Her full interview with John Shaw, as part of the Institute’s Understanding Our New World series, is available for free on the Paul Simon Institute’s youtube channel and website.

Staff reporter Ryan Jurich can be reached at rjurich@dailyegyptian.com. To stay up to date with all your Southern Illinois news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement