Abortion funds, providers prepared for threats and abortion restrictions long before Texas rule was upheld

Alison Dreith, the deputy director of Hope Clinic for Women, has faced threats from anti-abortion organizers for years, some in the form of legal attacks aiming to restrict access to the medical service, and others threatening her life.

“I got one [death threat] by one of the people that was arrested at the [Supreme Court Justice Brett] Kavanaugh hearing,” Dreith said. “Then, I started to get threats at my house instead of at work, and so I was like, ‘okay, it’s time to go. They found our address’.”

Dreith, said many older abortion providers who have experienced past trauma from anti-abortion extremists still live in fear of terroristic retribution.

Advertisement

In August of 1982 Dr. Hector Zevallos, the director of Hope Clinic at the time, and his wife were kidnapped by extremists in the group Army of God, according to the New York Times.

Dreith said another doctor at Hope clinic who has been working since 1995, now in his 70s, still fears speaking to the press. However, a younger generation of advocates are working to reverse the national climate of abortion stigma, Dreith said.

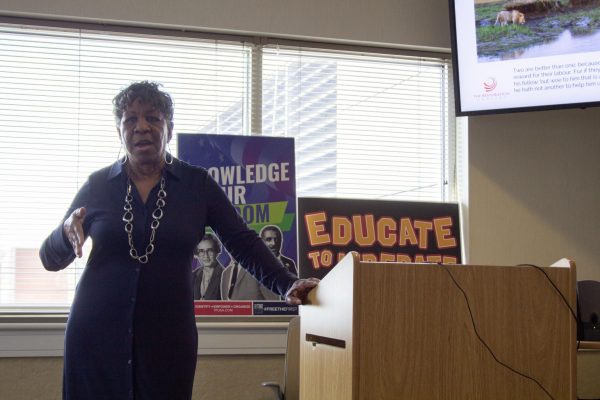

Qudsiyyah Shariyf, the 24 year-old program manager at Chicago Abortion Fund (CAF), said it’s more productive to describe the fund’s work and views as pro-abortion, as opposed to pro-choice or other language that obscures structural issues in accessing abortion services.

“We’re actually a part of a coalition with other reproductive health and justice organizations in Illinois, and we’re working on pursuing our policy agenda that is grounded in reproductive justice, and not just reform,” Shariyf said. “Really creating sustainable and systemic change that creates the possibilities for people to make choices.”

CAF, one of the oldest abortion funds in the country, has rapidly increased their support directly funding abortions for the last three years. Shariyf said the organization funded 183 people in 2018, over 800 people in 2019, over 1600 people in 2020, and has already passed 1600 people two-thirds of the way through 2021.

Hundreds of requests for support come to CAF from outside the state, most often Indiana.

“In July, we had over 340 requests for support, and, pretty much month to month, we’re seeing somewhere between 250 and over 300 calls,” Shariyf said, and the fund has so far filled every request.

Advertisement*

Meg Stern, the abortion support funds director at Kentucky Health Justice Network (KHJN), said the network has supported over 5500 callers since it launched it’s help line in 2013.

Midwest Access Coalition (MAC), another practical abortion fund, provided over $223,000 to pay expenses for people seeking abortions around the country.

Dreith, Shariyf and Stern are part of a web of staff, volunteers, and donors organizing nationwide to ensure anybody who wants or needs an abortion can get one.

“We also don’t think that anyone owes us an explanation for why they need that support,” Stern said.

Dreith grew up in Alton, Ill., and was a student at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (SIU-C) in 1999.

“You know, [I] flunked out in my first year,” Dreith said. “I remember there was a group of retired women that would drive patients from Carbondale and southern Illinois up to Hope every Saturday.”

After about six years in Carbondale, Dreith said she spent about 12 years organizing for abortion access in Missouri.

Dreith started at Planned Parenthood in 2009, the day after Dr. [George] Tiller, a Kansas physician and abortion provider was murdered.

“That was close to home from Missouri,” Dreith said. “Dr. Tiller was a person who physicians were friends with, were colleagues.”

The following year, in 2010, Stern said KHJN conducted a statewide survey to determine the biggest barriers to abortion access.

“We learned what we would have guessed, which was that the five biggest barriers to abortion access were funding, transportation or travel, lodging for overnight accommodations for those who have to travel out of town, as well as childcare and language interpretation,” Stern said.

Those obstacles have become more acute in Kentucky, Stern said, as the supermajority of Republicans in the state legislature, “have reiterated every year since [2017] that restricting access to legal abortions is top priority for them.”

Since then, Stern said she’s kept a contingency plan for what KHJN would do if abortion were banned in the state and the last clinics were forced to close.

Most people seeking abortions, and funding, would be directed to independent clinics, such as Hope Clinic for Women, located in states where abortion access has been legally protected.

“Because of people being emboldened by what happened in Texas… we suspect many more states can go,” Dreith said. “Hope is well prepared to take on that patient load. Our building was built to see about 10 thousand patients a year, and we’re only seeing half of that, so we can see a lot more patients.”

For now, though, the abortion restrictions upheld in the Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt case at the end of August have yet to make abortion illegal, even in Texas, Dreith and Stern both said.

“Even in Texas, people can get abortions before six weeks,” Stern said. “And there’s a lot of support for people that need to leave Texas.”

Cindy Buys, a law professor at SIU-C, said there are already legal challenges at the federal and state levels to the Texas case that will take a long time to work through the courts.

“The Department of Justice has sued in the state of Texas to block the implementation of the Texas law. They’re scheduled to hear the first oral arguments on that on October 1,” Buys said. “There is a lower federal court in Texas that already has prevented one of the pro-life groups from being able to sue Planned Parenthood in Texas, under the law.”

Dreith, Shariyf and Stern said that while their organizations have been preparing for a world in which abortion access is extremely restricted, it will take a larger movement to reverse course.

“We need the rest of society and our allies to come on board because, as I mentioned, I think other marginalized groups will certainly be next,” Dreith said. “This is all just, you know, a big build up to the death rattle of White supremacy. So, we’ll keep on fighting.”

Staff reporters Jason Flynn and Jamilah Lewis can be reached at jflynn@dailyegyptian.com and jlewis@dailyegyptian.com or on Twitter @dejasonflynn and @jamilahlewis. To stay up to date with all your Southern Illinois news follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement