“Love in the Time of Fentanyl” screens in Carbondale

February 8, 2023

An old man gazes into the camera, the skin of his face pressed so tightly against his skull that when he opens his mouth to groan his cheeks seem to disappear completely. His is the kind of desperate emaciation reserved for somber humanitarian footage of food-poor African villages, or grisly photos of government-engineered famines in nations long ago consigned to the fringes of public awareness by endless turns of war and exploitation. There is no war in this man’s country. There’s been no war this part of the continent for hundreds of years, except the one against him himself, his neighbors, and even those that now tend him as he flaps his hands panickedly.

—

“This overdose crisis is now killing over 100,000 people a year in the US,” said Colin Askey, director of ‘Love in the Time of Fentanyl’. “People who use drugs, especially crack, meth and opioid users are some of the most marginalized people in our society. They’re excluded from almost all services. They’re decriminalized, stigmatized, and they’re pushed into the shadows.

Advertisement

—

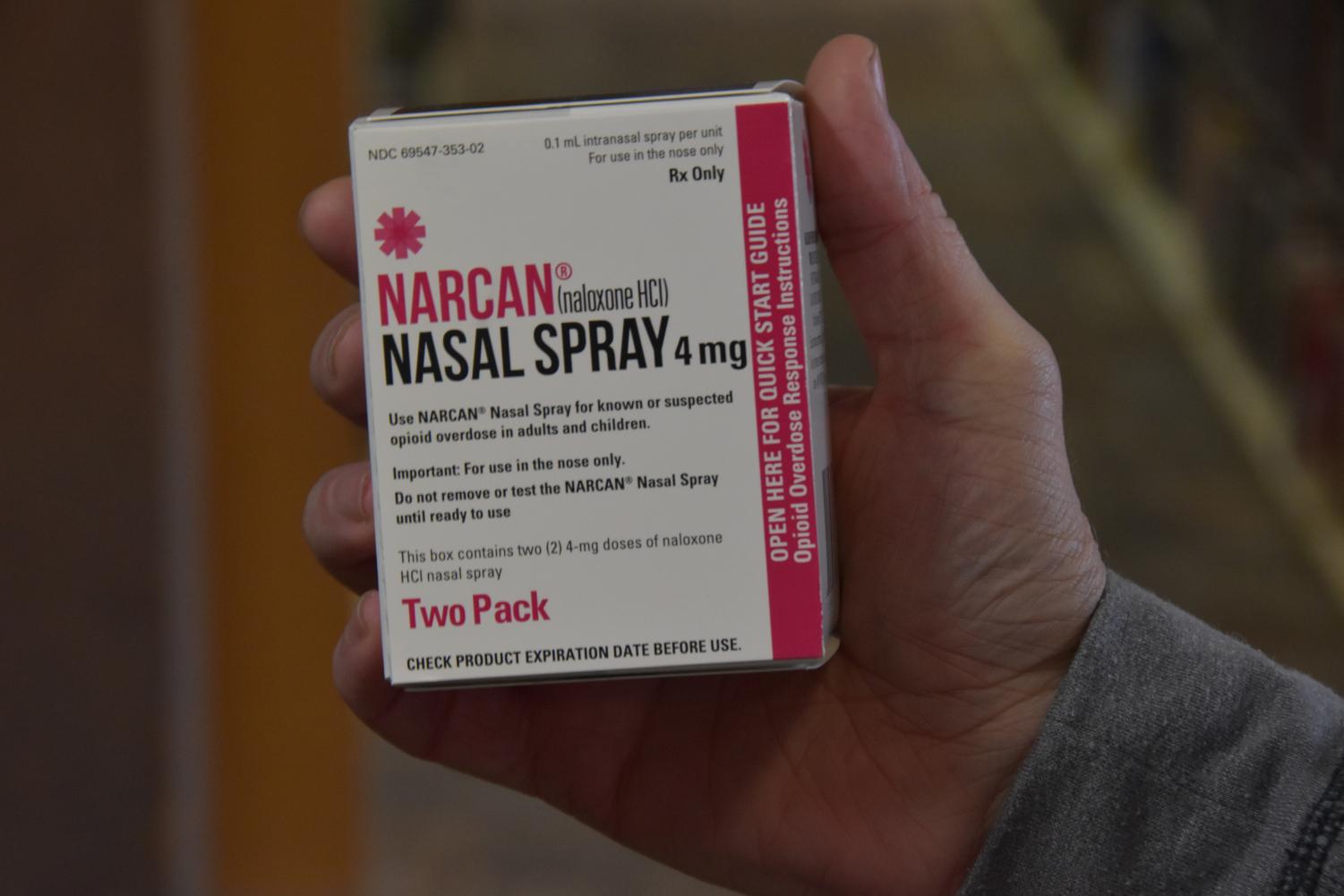

A handful of plainclothes workers fuss with tubing and needles and tersely recite the patient’s heart rate and oxygen levels. A casual, calm voice tells him to try to relax, and his panic seems to ebb as lifesaving Narcan is injected somewhere beneath the nest of tubing and straps that entwine him and his wheelchair. OPS, the Overdose Prevention Society, may well have been the only souls in the world that knew or cared whether or not he overdosed in the entirety of that black Vancouver night. It would certainly be true of many of that groups’ Downtown Eastside safe injection site, one of the poorest zip codes in the region.

“The vast majority of people from the downtown Eastside aren’t born and raised in the Downtown Eastside,” said Eric Spurling an OPS worker who traveled from Vancouver to Carbondale for a screening of the film. “They’re flocking from everywhere because that neighborhood is one of the only neighborhoods that has the social programs in place to support people who are struggling. If you’re homeless and you’re living in Alberta where it reaches negative 40 degrees you don’t stand a chance. If you’re a drug user in small-town nowhere where everybody knows everybody and you’re immediately ostracized from any sort of community that you know, you don’t stand a chance.”

Later in the documentary, a member of the Overdose Prevention Society brings Ron Mackenzie his electric wheelchair, which was left on the curb when the ambulance arrived and spirited him away to a warm hospital bed in a white sterile room. There he lay in a small draped off corner capable of only the shortest of responses. His eyes glowed with joy from sunken sockets as the man promised him fast food on his next visit. This was Mackenzie’s last overdose. He never came back from the hospital.

“When people have this conceptualization of heroin users they have this idea of this needle poking addict crouched behind the dumpster,” said Spurling, who used stimulants before joining the OPS. “And that’s not the case right? For everybody. There’s there’s people that use heroin that will work nine to five jobs, who have 401K’s. Sometimes they might just do it once or twice on the weekend, but the street supply of drugs has become so dangerously volatile and unpredictable. It doesn’t matter if you use habitually every day or if you use once a week. You’re playing Russian roulette every time you score, however frequently or infrequently you use.”

It’s hard to find someone that hasn’t encountered the horrors of drug use in their lives. Nearly everyone knows the words “crackhead” or “tweaker”. They’ve seen people on the streets talking to walls, or in an alleyway slack with heroin warmth. They’ve likely seen videos and pictures online. People with rotting teeth or their noses eaten away by chemicals, their skin encrusted in itching scabs. From these and decades of dismissive media coverage, they understand drug users to be dirty, mercurial, useless people that ooze with so much illness that even touching them might infect one of their betters with their afflictions of poverty, minority status, and addiction.

According to Independent Lens, a weekly documentary TV show on PBS that will air “Love in the Time of Fentanyl” on Feb. 13th, we have Richard Nixon’s war on drugs to thank for much of our current attitudes towards drug use. The discussion guide for the showing quoted Nixon’s top aid John Ehrlichman in a confession about the presidency’s intentions:

Advertisement*

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Despite numerous scandals rocking the Nixon administration, subsequent presidents continued the war on drugs trend, perhaps taking notice of the brutal consequences of doing drugs, or the harsh conditions in which drug users exist. More often though, they hated drug usage as a manifestation of contagious laziness, poverty, and lack of respect for authority.

Spurling and the OPS at large see drug use less as something which transforms users into these spectors of modern capitalism all by itself, and more as a vice that the desperate, the poor, and the unwanted are already prone to, used by political entities to selectively stereotype and label unwanted groups without being accused of racism or political malfeasance.

“We tend to penalize pre-existing behaviors in a mechanism to uphold power structures,” said Spurling. “This topic of discussion isn’t original. The same has been said before about countless other marginalized populations. If you look at the 13th Amendment, for example, the US abolished slavery and in response a scourge of unjust laws got put in place to keep African Americans in the prisons working for cents on the dollar.”

Presently, according to drugpolicy.org and the FBI’s own crime data explorer, Black people make up 24% of arrests for drug crimes, despite making up 13% of the US population and consuming/selling drugs at the same rate as White people.

“Anyone can do this exercise,” Spurling said. “Name a drug and think of the immediate stereotypes that come to mind. What do you think of when I say cocaine? What if I say crystal, or crack? Cocaine is thought to be this fun Wall Street type of drug – living like a Rockefeller – this is for the sophisticated. And, even though it’s damn near chemically identical, its cousin crack is thought to be this: vilified, reserved for the poor and any kind of inner city scum.”

At OPS there is an entirely different philosophy towards drugs: drug use is going to happen as long as there are people with problems, but that doesn’t mean that all drug users will turn to crime and become unemployed.

“Drug users are the backbone of the OPS,” Spurling said. “It’s peer-run and peer-led because who better to assist a drug user than a present or former drug user that’s been in their shoes. Lived experience seems to get discounted a hell of a lot. It seems that fancy paper and peoples credentials is all that matters. It’s my firm belief that drug users know more about pharmaceuticals than a lot of pharmacists, they know more about laws than a lot of lawyers, and they know more about prison systems than a lot of correctional officers because they’re the ones living it.”

Thanks to province-wide exemption to laws criminalizing possession of small quantities of hard drugs, British Columbia has several safe consumption sites run by former or even current drug users. As part of an extensive movement for harm reduction pushed by organization from all parts of society in Vancouver, the first of these, Insite, opened in 2003. This was only possible because of a federal exemption from provisions of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act concerning trafficking, allowing Instie to provide a safe space for vulnerable drug users to use with clean needles and nurses nearby. Extensive legal battles with the federal government followed when Canada’s Conservative party came to power and refused to renew the exemption, culminating in a ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada that made the site legal.

According the Public Division of Health Services, Insite averaged 337 injection room visits per day in 2018, with 1,466 overdose preventions and thousands of clinical treatments for other medical issues such as vaccines or wound treatment. In many cases Insite provided its patient’s only interaction with the healthcare system.

“It’s low barrier health care without judgment,” Spurling said.” It’s looking at someone eye to eye and valuing them for who they are, seeing the human in them. They aren’t a drug addict first, they are a person who happens to use drugs.”

OPS was originally started by Sarah Blyth, who ran the operation illegally out of a tent, with only clean needles and CPR to offer those who overdosed. Now the OPS has its own building and is able to pay workers as well as administer Narcan in the event of an overdose, even patrolling the streets in Downtown Eastside to clean up used needles and treat overdoses.

Other groups in the community, taking inspiration from the success of the previous harm reduction measure, have grown even bolder. DULF or the Drug User Liberation Front has started purchasing heroin, cocaine, and meth and verifying that it is pharmaceutical grade – and fentanyl free – before giving it away at no charge to those who need it.

“Imagine going into a coffee shop, Spurling said. “And you order a decaf with no caffeine. And the barista behind the counter gives you a cup with four shots of Espresso. Like this isn’t what I ordered, right? I drank this thinking that it was decaf and you just gave me four shots of espresso. Had I known it was four shots of espresso, I would have dosed accordingly and I maybe would have sipped it instead of chugging the whole thing. People go to the park intending on buying heroin or they go to their dealer intending on buying heroin and they might receive partial heroin part fentanyl or or they might receive fentanyl completely. And there’s just no safety right now.”

DULF provides labels telling users exactly which chemicals are in the drugs they’re consuming, hoping to provide those addicted to opiates and other drugs a cheaper, easily sustainable high to fight record overdose rates in recent years. Having recently celebrated its 6th month of providing free drugs, the organization urges the government to establish a supply of drugs for those who no longer have a choice in whether or not they take them. Even in the event that a drug user gets clean, felony drug convictions often see them shunned from most forms of employment, leaving them without community support or the comfort of using. Those who do move on in life must still suffer the pain of seeing their friends pass from overdoses and poor health.

“What experience has emphasized for me is sustainability; how it’s hard to do this over the long haul,” said Ronnie Grigg, a long time member of OPS. “I’ve burnt out, I have witnessed other colleagues burnout and how we care for that is a major question. You know, in some ways we’ve engaged really dark places willingly, right? And some without choice. That’s unique thing about the drug user is that they haven’t had much of a choice to engage with the trauma, the grief, the loss of this crisis, let alone what their personal experience for their own life and their their own trauma and grief and loss and yet our staff don’t get to new world changers. Like so many people in drug use they’re shunned from community engagement and shunned from being recognized as significant and yet, here we are.”

At the moment “Love in the Time of Fentanyl” was filmed, several of the iconic workers at OPS burnt out including “narcan Jesus” Ronnie Grigg, a man who worked with OPS for a decade before Mackenzie’s death took its toll on him. Even the most unflappable figures of the OPS can’t wander alleyways forever, no matter how decorated they are.

The community of Downtown Eastside has fought tirelessly for reform from their government, with great success. But the issue has barely cleared the table in the United States, where the first safe injection sites were only recently opened in New York in November 2021. That same year, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill approving safe injection sites in major cities, saying, “Worsening drug consumption challenges in these areas is not a risk we can take.”

If there is one message the OPS wants to deliver to those who watch “Love in the Time of Fentanyl”, it’s that sweeping drug users off your porch and onto the next one isn’t a solution in a time where anyone can be a drug user. The system is strained when only one city is sympathetic to those in need.

“Before drugs were ever a problem, drugs were the solution to all of my problems, because drugs were the social glue that held all of my friendships together,” Spurling said. “I didn’t care how we were different. I didn’t care if I grew up different from you or what I had and what I didn’t have, where my family was because we had this thing in common.

In Bruce Alexander’s rat park experiment, the rats would self administer [drugs] only when the cage was desolate and bare. And here in the US when we’re assigning punitive disposition after punitive disposition we’re literally taking people who have a substance dependency problem not criminals. And our solution is literally tossing them in empty and desolate cages.”

To Spurling, the OPS is life, community and purpose which drives him to respect himself and care about his actions. The criminal justice system is none of those things.

“We really think that this is going to make things better, brandishing people with a criminal record, like a scarlet letter,” Spurling said. “Where they just have a felony for life. No homeowner ever wants to rent to him. It’s impossible for them to get a job. They have to check off the embarrassing checkbox on every job application they ever submit. How’s this supposed to reintegrate people into the community if a lack of community is the driving problem in this for a lot of people?”

Daniel Bethers can be reached in instagram at commonitem6damage or at [email protected].

Advertisement