Book Review: Kim Kelly’s Fight Like Hell is an inspiring introduction to working class struggle

June 15, 2022

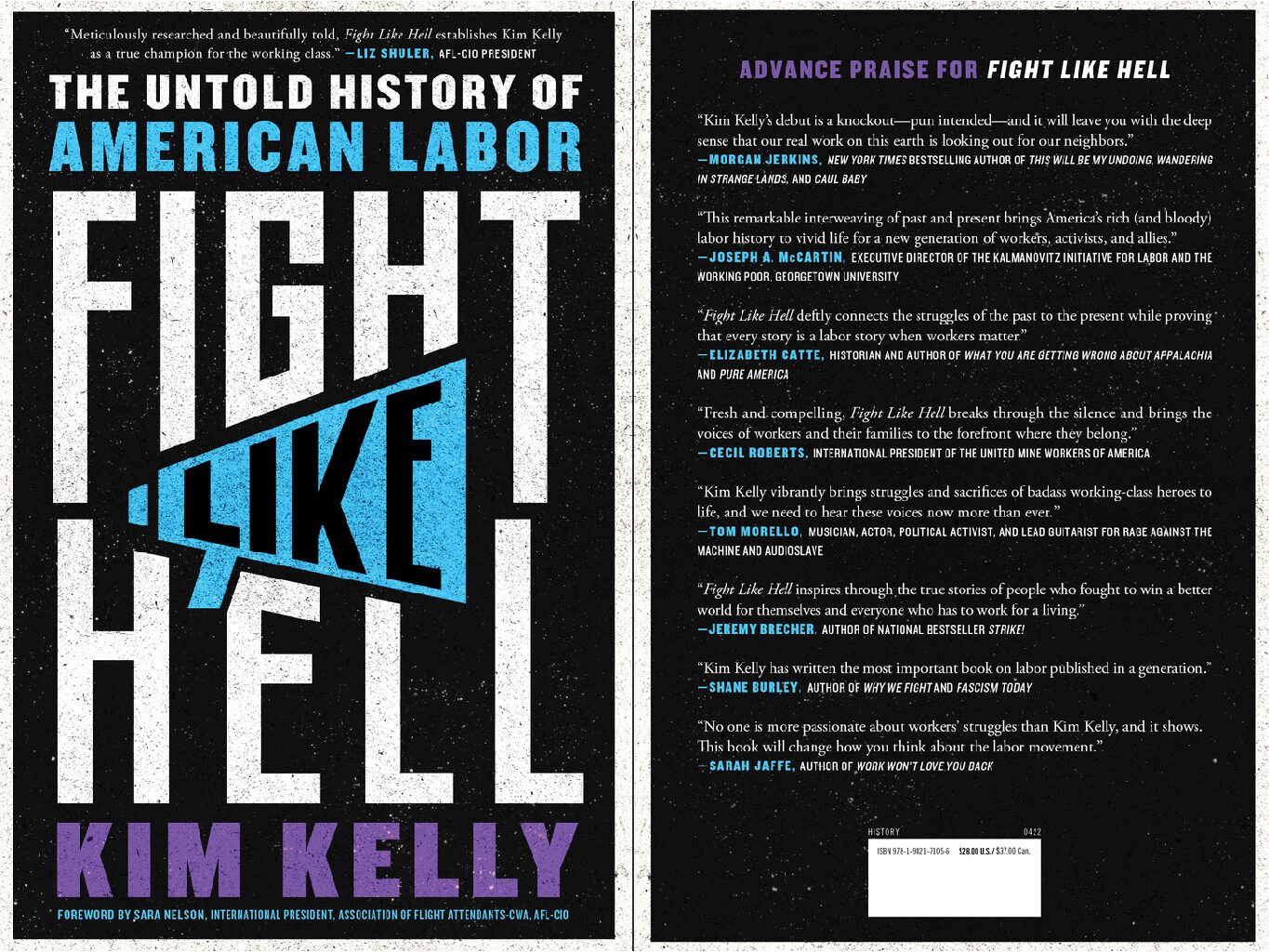

Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor is a great primer on the breadth of struggle in the US labor movement. The book features a series of more or less standalone essays generally organized by labor sectors or by identity groups.

Author Kim Kelly brought together a wide variety of stories in the book.

Many of the events she recounts, like the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, the United Farm Workers campaign and the Attica prison uprising, will be familiar even to people who don’t typically pick up history books or follow the labor movement. But, Kelly’s focus in these famous events is generally on lesser-known participants.

Advertisement

Fight Like Hell also features the contributions of some US titans of history, like Ida B. Wells, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, but in Kelly’s retelling the focus is on their relationships and contributions to the labor movement.

Randolph, for example, is generally best-known as a leader in the March on Washington, and Rustin as one of its primary organizers. As Kelly points out, though Randolph was a longtime socialist labor organizer and Rustin (who had a “flirtation with the Communist Party”) was a longtime advocate for economic empowerment, the march has since been scrubbed of its focus on labor issues.

The bulk of the book is dedicated to campaigns and struggles that, outside the world of historians, activists and their avid readers, will be totally new to most people.

I grew up in Alpharetta, Georgia, a rural-town-turned-suburb 30 minutes north of Atlanta. Nobody in my schools or community ever mentioned the 1881 strike of Black domestic workers spearheaded by the Washing Society. I’d also never been told about the 1934 textile strike which then-Governor Eugene Talmadge directed the Georgia National Guard break, or the at least 100 strikers imprisoned at Fort McPherson.

Fight Like Hell also details fights for immigrant workers, prison laborers, sex workers, Indigenous laborers and people’s fights to end work exclusion, like those of disability activists, Black people and women.

The book is at its best when Kelly details her original reporting, or what she’s called a “blood and guts” depiction that brings in texture and personality to the amazing people and events she draws from.

Because the book is organized thematically, there are numerous leaps backward and forward in time. This occasionally leads to structural issues where people are lauded for being ‘first’ at something, only to have their ‘first’ pre-empted later in the book.

Advertisement*

A section about Ida Mae Stull, a disabled, Ohioan woman lauded for breaking the glass-ceiling for female coal miners, is followed by a section about Black slaves forced into mines, with an acknowledgement that Black women were at times also doing this work scores of years before Stull.

Kelly mentions, a few sections later, Indigenous people had been mining on the continent for generations before the arrival of European settlers. Presumably, some Indigenous women were also part of that work.

The upside to the compromise on clarity when jumping between time periods is that the reader is guided into making connections between current and past labor fights.

For instance, the chapter on sex work opens with a retelling of the 1969 police raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York City, which incited a now-famous LGBTQ+ uprising. Kelly connects the stories of that uprising’s participants, like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, to their spiritual forebears and acolytes, like female reformatory inmates, gilded-age immigrants, AIDS crisis activists, strip club union organizers and contemporary online content creators.

The result is a sort of tapestry representing the kinds of multi-pronged networks of people that make major societal changes possible.

Working in coalition, despite and often because of people’s varied identities and experience, is the major connective thread across Kelly’s telling of US labor history.

One of the highlights of this coalition work is the Great Sugar Strike of 1946. After years of violent repression, the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) countered a move by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association by infiltrating a scab hiring operation in the Philippines.

The multi-ethnic, multi-language coalition that formed in Hawaii was able to work through national differences between groups that were very recently fighting each other during World War Two in order to win major concessions from the companies, and pave the way for future victories for agricultural workers.

If there’s a sort-of template for activists that could be pulled from the book, it’s definitely this sort of international, cross-experience blueprint.

There’s a degree of rah-rah cheerleading throughout that some might find cheesy, and others enheartening. A section about suffragist Frances Perkins, for instance, describes her goal of supporting, “‘plain common workingmen’,” while in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt presidential administration, and ends with, “that is exactly what she did”

Regardless, Kelly’s absolute sincerity outweighs any whiff of after-school-melodrama.

Fight Like Hell isn’t a parade of feel-good victories. Each chapter recalls the difficult losses that built toward any successful labor campaign and incomplete work that it will probably take generations to finish. Kelly also acknowledges that US labor unions also have a long, bitter history (and often present) of exclusion based on various identity factors, and that even inclusive or progressive unions often fell short of their own stated values.

The book also captures the role police, military, courts and politicians have played, over and over again, in snuffing out labor actions.

Fight Like Hell is by no means an exhaustive account of US labor history, and Kelly doesn’t claim that it is. She’s acknowledged some arguments that stemmed from the marketing campaign for the book, which included changing the subtitle to “The Untold History of American Labor.”

In a discussion about the book streamed online, Kelly reiterated that the stories she’s collected in Fight Like Hell have, in fact, been told many times over.

Each of the people detailed have already told parts of their own story, were the subject of, often, piles of news articles, and have since been the subject of one or more history books. Kelly’s work is more of a recontextualization and repackaging of that past work in a format that’s digestible for a mass audience.

As a result, it’s a great reference for reading groups or class discussions, and, because of its extensive sourcing, Fight Like Hell is also an excellent starting place for people interested in digging deeper into labor history.

Jason Flynn can be reached at [email protected], by phone at 872-222-7821 or on Twitter at @dejasonflynn. To stay up to date with all your southern Illinois news, follow the Daily Egyptian on Facebook and Twitter.

Advertisement