For Dallas’ Holocaust survivors, the past has suddenly become painfully present

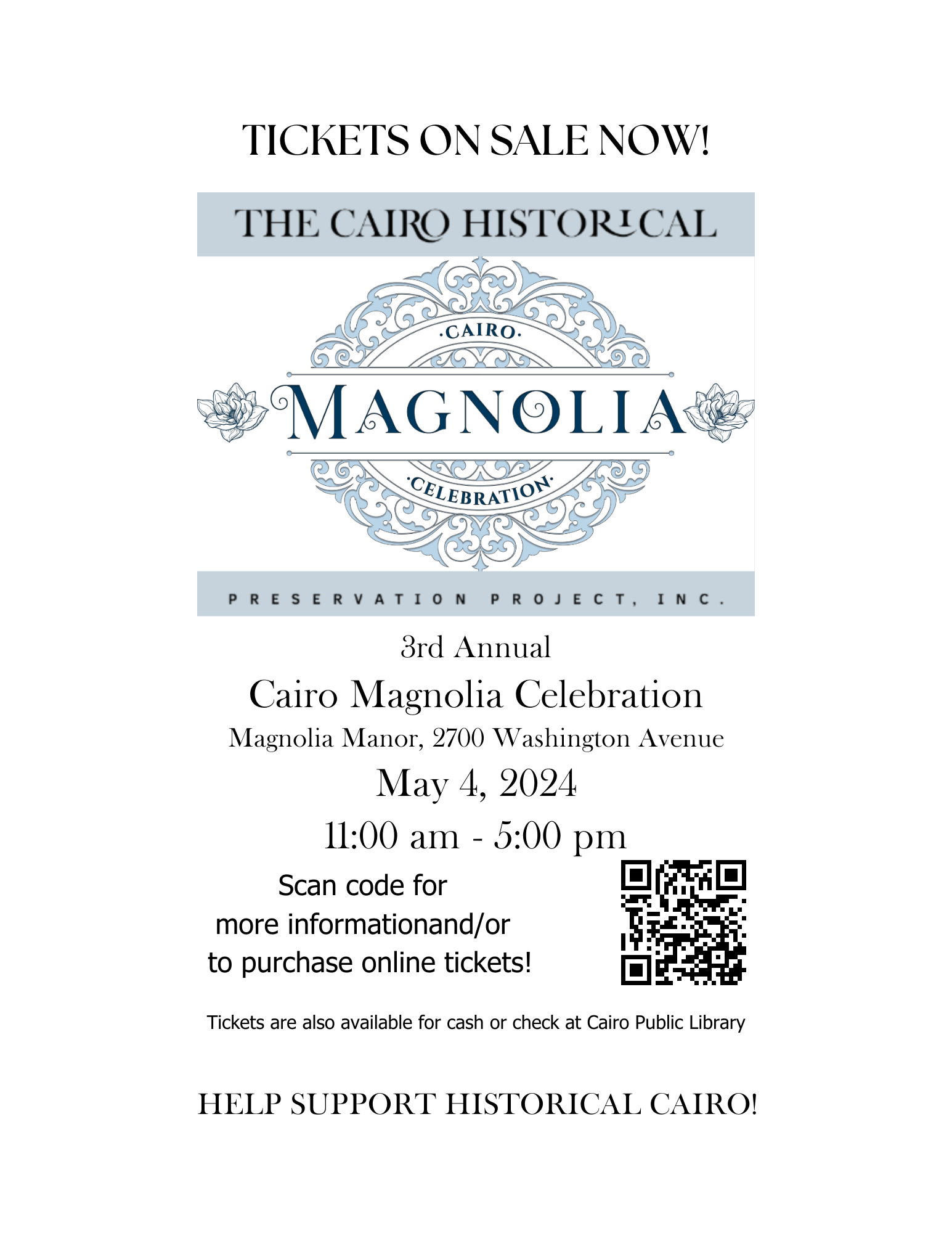

Max Glauben, a Holocaust survivor, with a “March of the Living” scarf at his home in Dallas on August 14, 2017. (Jae S. Lee/Dallas Morning News/TNS)

August 17, 2017

Monday afternoon I called a man I’ve known for years, Max Glauben, the 89-year-old son of Warsaw, Poland, made an orphan by the Nazis. “How did you know I was going to call you?” he said when his wife handed Max the phone. I asked about what. But I knew.

“About the stuff that’s happening right now,” he said through the accent that has been tempered only slightly after decades as a U.S. citizen. And then Glauben, who survived six concentration camps and a death march before being liberated by U.S. armed forces, told me what it was like to turn on the television over the weekend and see Sieg-Heiling, “Jew will not replace us”-spitting, “blood and soil”-shouting white supremacists carrying swastika flags down American streets.

“It was just unbelievable, just unbelievable,” said Glauben, who came to this country 70 years ago next month and, shortly after, was drafted into the U.S. Army.

Advertisement

He said he had to close his eyes, because he hurt all over. But, he said, the past began to overwhelm the present unfolding in Charlottesville, Virginia, where authorities said 32-year-old Heather Heyer, a woman who dared to protest Tiki-torch-bearing neo-Nazis swamping her streets, was killed by a 20-year-old man from Ohio who idolized Hitler.

“And everything that happened in 1939, ’40 and ’41 to me in Warsaw, Poland, gets right in front of my brain,” Glauben said. “My eyes don’t want to see it again. I have to close my eyes so I wouldn’t see this. But all my feelings are coming back.”

So, too, the memories. Of the Warsaw Ghetto and “not being able to go out in the street by myself without somebody wanting to hurt me because I was a member of a certain religion.” Of Nazi soldiers on sidewalks and street corners who threatened to shoot him if he looked them in the eye. Of being transported to a camp in a crowded, fetid boxcar where prisoners fought for tiny drops of water falling from the ceiling just to wet parched lips. Of his mother, father and brother being executed in the death camps.

Glauben was among the founders of the Dallas Holocaust Museum when it was just a room in the Jewish Community Center’s basement. When we spoke almost a year ago, he warned that we would again see neo-Nazis, the Klan and white supremacists marching in the streets.

He’d heard obscene whispers escalate into violent bawls coming from supporters of the would-be president; he saw a St. Mark’s graduate ascend to the top of the hatemongers’ trash heap. He even went to Texas A&M last year, on the same day that graduate, Dallas native Richard Spencer, was there spouting his alt-right bushwa, in the hopes of turning bystanders into upstanders who would combat the hate now eager to show its face in broad daylight.

“This is how it started, with them doing this,” Glauben said Monday, his TV tuned to the footage. “Then killing my family. Right now I am looking at it. On MSNBC, they’re repeating it and repeating it. And what does a child do if he’s 10, 12, 14 and sees people raising their hands and saying, ‘Heil Hitler?'”

I tried to reach several Dallas survivors Monday, but found few willing or able to talk about the images looping, almost nonstop, on cable news. Some couldn’t speak, their memories having faded into the fog. Others, traumatized all over again, wouldn’t speak.

Advertisement*

But then there are women like 89-year-old Marianne Rubin, who, on Sunday, became a viral star. During a rally in Union Square in New York City, she was photographed holding a sign that read, “I escaped the Nazis once. You will not defeat me now.” I went to Glauben’s house Monday evening and showed him the photo of the woman who had escaped Nazi Germany with her family in the 1930s. He grinned and said only, “Wow.”

Ninety-three-year-old Jack Repp, too, was eager to talk. We’d never met until Monday, but he told me of our connection: For decades, he owned a department store on Second Avenue, across from my grandfather Harry’s auto parts store. Most of my grandfather’s family had been killed by Nazis, and Repp said they would often get together to speak Yiddish — a dying language, especially in South Dallas in the 1940s and ’50s.

Repp was 21 years old and 69 pounds when he was liberated from a concentration camp. “I was 99.9 percent dead,” he told me, “but I still had my mind.” Like Glauben, he travels the world recounting his story — one, he said Monday, that began with images like those seen on television over the weekend.

“They used to go in small towns beating up Jews and burning up homes, and this is is exactly how it looked,” Repp said. “It reminded me of the pogroms. It reminded me so much of that, I was sick. I couldn’t leave the house for two days. When you see something like this as a Holocaust survivor … ” He paused, sighed.

“I never thought I would see something like this in America.”

___

(c)2017 The Dallas Morning News

Visit The Dallas Morning News at www.dallasnews.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Advertisement