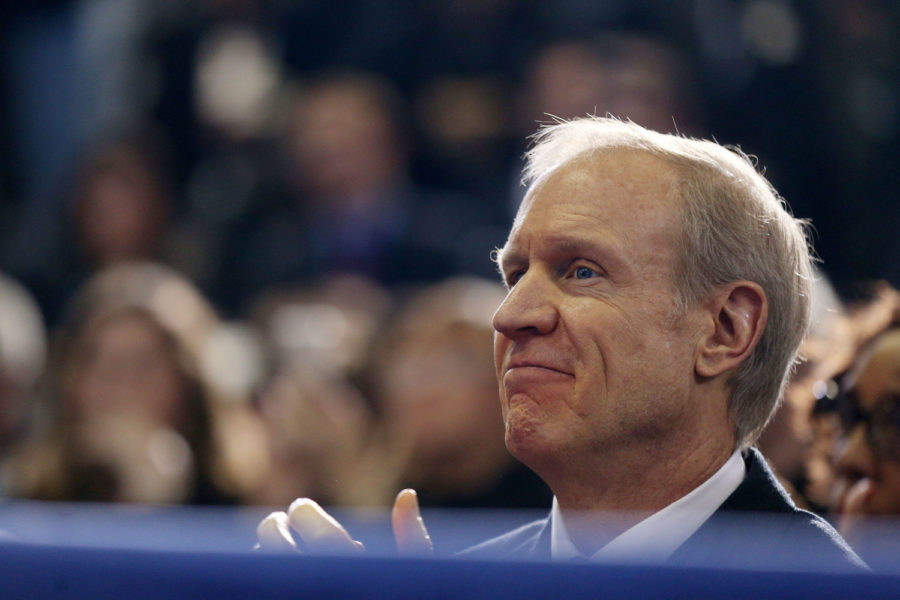

Rauner stays out of spotlight on bill signings

August 24, 2015

Moments after Gov. Bruce Rauner signed a landmark public safety bill into law at a closed-door ceremony, the lawmakers who had ferried the bill to his desk walked two stories below the governor’s office to the press room in the Capitol basement.

There, a handful of Republican and Democratic legislators held a news conference to herald the law, which made Illinois one of the first states in the nation to put in place a statewide system for equipping police officers with body cameras. The scene earlier this month left some scratching their heads.

The rookie Republican governor had passed up an opportunity to publicly tout a rare bipartisan achievement as he struggles to gain traction in his fight with Democrats reluctant to approve his pro-business, anti-union policies. It’s a time-honored tradition for Illinois governors to invite lawmakers, journalists and members of the public to ceremonial bill signings, an easy way for the chief executive to take credit for accomplishments and create a sense that he’s getting things done.

Advertisement

Rauner has signed more than 400 bills into law since he took office in January. He has held zero public signing ceremonies.

Asked why that’s the case, Rauner spokesman Lance Trover did not directly answer the question but did say the “work of the General Assembly is not done.”

The governor’s allies in the General Assembly put a finer point on it: The stalemate has set up a situation where Rauner has tried to keep the focus on his agenda and the pressure on Democrats to pass it. Highlighting the achievements of others would detract from that effort.

“Bill signings are ceremonial, and they’re meant to be almost like victory laps,” said House Republican leader Jim Durkin of Western Springs. “I don’t see any reason why anybody would be celebrating what has happened in Springfield until we get a budget done.”

Instead, Rauner has opted to have small groups in his office for private signings away from the glare of the media. Sometimes, his team posts photos from the gatherings on Facebook and Twitter.

In one case, the governor’s office distributed a video of Rauner signing a bill to help ease the way for the Barack Obama presidential library and George Lucas museum in Chicago. But signing ceremonies also carry risk, as they allow reporters to observe Rauner interacting with people and provide a chance to ask him questions.

{{tncms-asset app=”editorial” id=”84c7c87c-49d4-11e5-b615-e741d8949cb5″}}

Rauner appears to enjoy shaking hands and taking photos with voters, but the political newcomer allows only brief and sporadic question-and-answer sessions in controlled settings.

Advertisement*

“This could be part of a trend to try to control what the message of the day is,” said Mike Lawrence, who was press secretary to former Republican Gov. Jim Edgar. “In other words, if you’ve got a bill signing and you do it with the media there, then the media ask you questions about other issues, that can overtake what you’re doing on the bill.”

Rauner’s predecessor, Democrat Pat Quinn, took the opposite approach. He’d regularly hold several bill signings a week, summoning reporters and lawmakers to schools, construction sites, television studios and hospitals to affix his signature to the official paperwork as television cameras rolled.

When Quinn signed the bill making Illinois the 16th state to legalize gay marriage, he held a rally at the University of Illinois at Chicago. More than 2,000 people looked on as he used more than 100 pens to slowly write his name a portion of a letter at a time.

The pens were handed out to dignitaries as souvenirs, a practice Quinn became known for even on less high-profile legislation.

Rauner recognized the benefits of such press pops early on. On his first full day in office, Rauner invited reporters into his Capitol office as he signed an executive order dealing with state employee ethics. Later that month, he marked Martin Luther King Jr. Day at a Southwest Side high school, where he signed an order requiring reports on minority and veteran participation in apprenticeship and training programs offered by companies and labor unions.

Some argue that with the stalemate and the state’s financial issues taking up much of the oxygen at the Capitol, this year’s legislative session has produced few opportunities for bill celebrations.

“This is minor league stuff in the grand scheme of things,” said Rep. Ron Sandack, R-Downers Grove, a Rauner ally.

But others see a number of missed opportunities where Rauner could have attempted to cool tensions at the statehouse, such as his signing of the police body camera bill.

“That would be an opportunity, were I the governor, to have a news conference and say, ‘This shows what can happen when people on all sides sit down and negotiate,'” said Charles N. Wheeler III, director of the public affairs reporting program at the University of Illinois at Springfield and a longtime statehouse observer.

In the current session, which is still ongoing because of the lack of a budget, lawmakers passed — and Rauner approved — a bill that brought back happy hours at bars; a package of laws aimed at keeping kids out of jail; new concussion policies for student athletes; and rules to help prevent sudden infant death syndrome.

In some instances, Rauner had no ceremony at all. That’s what happened with the concussion bill, which sponsoring Sen. Kwame Raoul, D-Chicago, brought on behalf of Lurie Children’s Hospital.

The new law sets rules for when students can return to school and sports after they’ve had a concussion. It passed the House and Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support.

{{tncms-asset app=”editorial” id=”569b50e2-fc2a-11e4-b441-6bd20285bac8″}}

Lawmakers asked the governor’s office to sign the bill at a ceremony at Lurie, but the request was ignored, Raoul said. Rauner signed it in private this month.

“That would have been a nice ceremony, given the concept came from Lurie,” Raoul said. “And everybody loves to be supportive of sick kids. It would have been a win, just from a pure political standpoint.”

In other instances, Rauner’s signings have had all the trappings of a typical ceremony but were held behind closed doors.

When he signed the sudden infant death syndrome bill, Rauner organized a private gathering in his Capitol office and invited the family of the boy whose death inspired the bill. It was an emotional moment for the family, said sponsoring Rep. Tom Bennett, R-Gibson City, who thought the governor was trying to keep the setting intimate out of consideration for the family.

“A lot of bills that we have, a lot of them come about because something happened to someone,” Bennett said. “And so that’s a personal story, and I think Gov. Rauner’s trying to be sensitive to that.”

Some think Rauner might be reserving the pomp and circumstance of a public signing ceremony for only the items that’s he’s personally advocated for, like the property tax freeze and union-weakening measures he’s been heavily pushing for months.

“Now, that would be something to celebrate,” said Sandack, the House member from Downers Grove.

Rep. Mary Flowers, a Chicago Democrat who has been in the General Assembly for 30 years, said each of the six governors she’s served with has had his own approach when it comes to bill signings.

“Some do fanfare, some governors don’t even notify you that the bill has been signed already,” Flowers said. “I’ve seen it all kinds of ways. I guess, to each his own, how they want to do it.”

Chicago Tribune’s Monique Garcia contributed from Springfield.

Advertisement