The high cost of higher education

October 17, 2013

Falling state appropriations could price students out of an education. But what is that degree really worth?

Appropriations, fundamentals among factors holding college students back

The rising cost of college has given new urgency to questions about the purpose of higher education and whether students are being priced out of their ticket to future financial security.

Advertisement

With four years at a public university costing an average of $72,000 and expected to rise to $97,000 by 2025, according to Time magazine, students are left to wonder whether the thousands they have invested will result in a bright future.

But Time’s statistics also show half of employers surveyed stated they had trouble finding qualified college graduates to hire, bringing up the question of whether college should be designed strictly to train students for the workforce or should be more about making them cultured through classes in the humanities and history.

As states across the country cut back on their support for public higher education, tuition rises and the pressure to make the investment pay off increases.

SIU President Glenn Poshard said he is worried that only the wealthy will be able to afford a college education.

“It’s easy to see that the future of higher of education is, the way it’s going now, it’s going to end up pricing out the middle and low-income families, and their ability to afford an education, a college education,” he said.

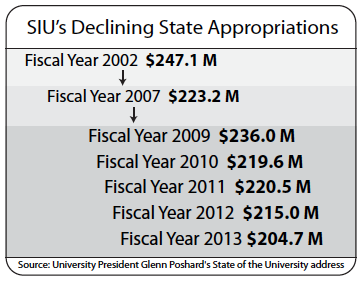

The university’s state appropriation, the money Illinois budgets for SIU, has decreased $42.4 million since fiscal year 2002, when the state budgeted $247.1 million for the university. Although fiscal year 2014 appropriations are expected to hold steady rather than decline again, increased tuition because of these lower appropriations could make college, the ticket into a middle class lifestyle for students, less attainable for their lower and middle class families, Poshard said.

“We don’t want to privatize higher education,” he said. “We want to make it remain open and public, as it always has been. That was the intent of higher education. It just seems like we’re taking that away. I worry about it.”

Advertisement*

Poshard said workers in the lowest income percentile in Illinois, specified as earning up to $19,000, give 77 percent of their family’s take-home pay in order to send one child to college. These pricing problems have contributed to the privatization of higher education — a process Poshard said is already in motion.

“If you’re going to force the middle class to contract rather than expand, where’s your tax base going to come from?” he said. “What’s the country going to build an education system on if there’s no middle class left?”

Former Chancellor and present architecture professor Walter Wendler said even though appropriations may remain the same, operational costs could continue to rise.

“Even if (appropriations) do remain stable, everything else is going up,” he said. “Healthcare costs, a gallon of milk, energy, everything increases, so even if our income stream remains flat, the cost of doing business goes up.”

Wendler said state appropriations are not likely to reach the heights they were years ago again. Tuition was flat at about 20 percent of the cost of education for many years, but it began to creep up in the late ‘90s and early 2000s to the range of 25 percent to 30 percent at colleges across the country, he said.

“Auxiliary costs grew — fancier dormitories, that sort of thing — and I’m not talking about SIU, I’m talking about general trends,” he said. “The costs of those things grew, which grew the cost of the total budget but tuition didn’t grow, so it remained about 20 percent for a long time.”

To make up for these rising costs, colleges nationwide are feeling a push to admit more students, but those students should be careful about their decisions concerning their college career, Wendler said.

“The college-ready demographic is growing, the college-prepared demographic is shrinking and university expenses are increasing,” he said. “One way to meet the increasing expenses is to bring in more students, and I think students should ask very hard questions and I think that it’s incumbent upon program leaders and so on at universities to be honest with the students.”

But for those students who can afford the costs and are admitted, there is also the question of whether they are fully prepared for the rigors of a college education. During the Sept. 12 Board of Trustees press conference, Chancellor Rita Cheng said the university is tightening its standards to ensure it is not admitting students who may not have a good chance at being retained.

“We could’ve had a larger freshman class,” Cheng said at the press conference. “We chose to not admit students that had a profile consistent with students who, in the past we admitted that we couldn’t retain because they weren’t academically successful. We no longer are going to try to build enrollment with students who are underprepared.”

The SIU 2012-2013 factbook shows that, of students who started their college career in the fall of 2006, 26.4 percent graduated within four years. However, Wendler said colleges are often judged on a six-year graduation rate. According to the factbook, 47.5 percent graduated within that time frame.

Poshard said while recruitment is important to the university, even students who come to SIU with good records of attendance and ACT scores will need help with the transition.

“Retention is even more important, because those students that come to us and have some need that needs to be rectified in that freshman year, we’ve got to pay special attention (to them),” he said. “That’s why you’ve got the university college, that’s why you’ve got the mentoring program and other things in place to try to help those students get through the first year especially.”

Jerry Becker, professor of curriculum and instruction, said new college students’ foundational knowledge and skills are lacking, leading to problems as they begin college courses and causing some students to take remedial classes.

“I think there’s no question that the background that students have in education, the knowledge that they have, knowledge and skills, when they come in is weak for a lot of students,” he said. “Of course what they encounter right away is higher expectations for reading, for writing, and doing arithmetic and math, and so on, and they can’t handle it.”

But for those students who complete that first year and make it to their college degree, the question of what they have really learned in their time at the university remains. According to a 2011 study, sourced in Time’s report, 36 percent of college graduates who were tested did not show significant cognitive gains during their four years of higher education. So should colleges focus on helping create a well-rounded individual through what is often called the common core, or focus solely on preparing students for their chosen field? Poshard said these two schools of thought can co-exist, but the common core of humanities courses is still an important part to the college degree.

“We can teach students to be an engineer, teach them math, teach them science,” he said. “But if we fail to teach them art and poetry and history and dance, the kinds of things that have acted as the glue for cultures to stand together and to understand each other and accept different lifestyles and different belief systems and so on, if we can make them better citizens that is an equal job.”

The common core can provide students the skills needed to get a job as well as the ability to function as a citizen who can deal with more complex ideas, Poshard said.

“A university education should be giving you both (types of skills),” he said. “It should be teaching you how to live as a citizen in a democracy while at the same time giving you skills to get a job.”

Becker said while the sciences and humanities are important, students must master the basics before they try to move forward in college.

“The other thing that’s really fundamental (to the sciences and humanities) is the basics,” he said. “Reading and writing, and basic math and science.”

Wendler said there is a connection between critical thinking skills and skills that have an immediate application in the workplace, but some colleges are failing to strike a balance.

“What you have there is a bad compromise,” he said. “I think the magic is to find that place in the middle of the road where you can do both with some level of accomplishment.”

Advertisement