Ethnographic photography exhibits cultural perspective

November 4, 2013

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month, a glimpse of American Indian cultural history is being exhibited at Southern Illinois University’s Morris Library.

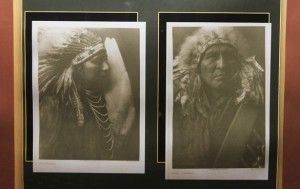

On Friday, 130 photographs of Edward S. Curtis’s series The North American Indian went on display in the Hall of Presidents and Chancellors.

The entire series consists of 20 volumes, documenting 80 different tribes over the course of Curtis’s 30-year journey. In that time, Curtis took 40,000 images and wrote around 4,000 pages of detailed narrative about their lives. While

Advertisement

Morris Library owns the complete set, the Special Collections Research Center holds 13 of these volumes, and offers researchers the unique chance to study these historic images firsthand.

Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History Jo Nast said, in the beginning, Curtis’s work was not being appreciated, and only after it was discovered in 1972 did the public take interest in his work.

“He was a pioneer in ethnographic photography,” Nast said.

Ethnography is the scientific study of the customs of cultures and the individual people within them.

Library Specialist at the SCRC Beth Martell said as people look deeper and deeper, they realize these people have

a much larger history and differences in costumes will become apparent.

“Now when I look at Native Americans in these pictures I see Tibetans, I see people from Asia,” Martell said.

Advertisement*

The pictures make people continually question the story behind the image, and show the diversity that was this culture, she said.

“You don’t think of Indians as Alaskans eating whales,” Martell said.

Professor and Dean Emeritus of the College of Mass Communications and Media Arts Gary Kolb said while creating this artwork Curtis used an expensive printing process developed in the 1860s called photogravure — one of

the finest of photographic reproduction processes.

“Photogravure is where you take a photographic image from a negative and transfer it onto a copper plate, and then you etch the plate and put ink on the plate and run it through a printing press and it transfers the image to paper,” said Kolb.

While the photographs and printing process were spectacular, not all white Americans who saw the publishing’s at the time believed Curtis’s work to be completely realistic, he said.

“People argued that what this was, was a commoditized recreation of a romantic vision that never really existed,” Kolb said.

Recreating these scenes consisted of finding the clothing and interviewing people. Not only did Curtis have the photographs, but he also had the transcripts, the interviews, songs and poetry to go along with it, he said.

“Participants had a degree of trust in what Curtis was doing and a degree of fondness for what he was creating, for what he was portraying,” Kolb said.

Retired SIU professor of photography Charles Swedlund said Curtis probably deserved more respect than he received, especially because his work appealed to photographers, archeologists and anthropologists.

“It’s interesting how his work goes both ways that way,” Swedlund said.

Curtis’ photographs are not only beautiful, but also have great significance to the history of American Indians, Martell said.

“All the history we have is what he gave us,” Martell said.

It all started in 1895 when Curtis photographed the daughter of Chief Sealth, Princess Angeline, which is documented as the first portrait of an American Indian. After being published more in 1906, J.P. Morgan funded Curtis’ The North American Indian project with $75,000 to produce a series, and the project caught the eye of President Theodore Roosevelt.

As Curtis gained support from Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan, Franz Boaz of Columbia University — the man who had established anthropology as an academic discipline — began to raise concern to Roosevelt of Curtis’s accuracy in the field.

Martell said this type of publicity would have embarrassed Roosevelt’s name, and as a result, Roosevelt put together a committee to oversee

Curtis’s methods.

Curtis sold all the rights and different

materials to J.P. Morgan’s son, J.P. Morgan Jr. in 1928, Martell said.

“In 1935, the Morgan Estate sold it to a publishing house for $1,000 plus a percentage of future rights, and then it was just warehoused in Boston,” Martell said.

An original piece today would go for millions, she said.

The display is available to see weekdays from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and is scheduled to be up until November 30, but it may be up all semester, Martell said.

History Associate Professor Grey Whaley will be giving a speech entitled the “American Indiana Activism and the Primitive Imagery in the Age of Edward Curtis,” alongside an hour-long open talk with Beth Martell Nov. 14 starting at noon.

The SCRC is keeping all the photographs laminated, and plan to keep reusing these images every November for Native American Heritage Month.

Luke Nozicka can be reached at [email protected] or 536-3311 ext. 254.

Advertisement