Asian carp invade Illinois waterways

January 17, 2012

The aquatic fugitives known as Asian carp have overrun the Illinois waterways since the 1970s, and continue to threaten the delicate ecosystem as well as human safety.

The fish escaped four decades ago during flooding of fish farms adjacent to the Mississippi River and are now throughout the Midwest. More recent flooding has brought them as close to Carbondale as Rend Lake and Crab Orchard Lake.

Advertisement

“An invasive species is one that is somewhere it doesn’t belong, and it becomes invasive by causing problems for other species,” said Matt Whiles, professor of zoology and director of the Center for Ecology. “Potential impacts of invasive species are competition with native species for food and habitat.”

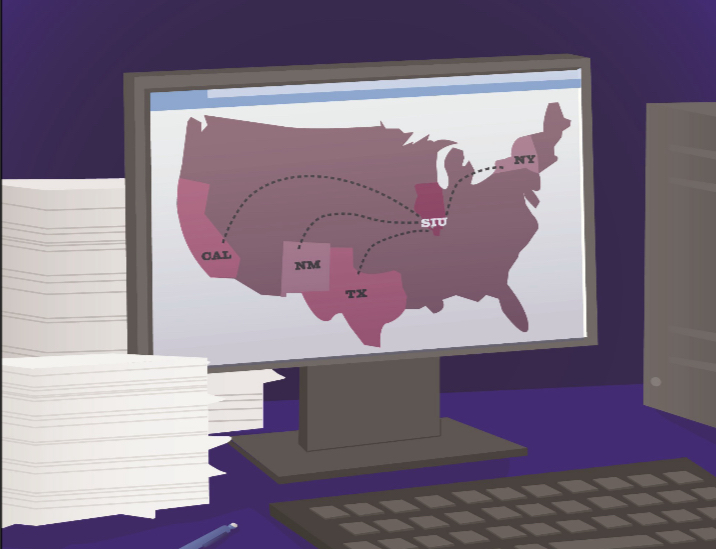

SIU and the SIUC fisheries are on the forefront of researching Asian carp, Whiles said.

Having just completed a $1.1 million grant on studying the carp, they were working to understand what influences the species’ movement and the differences between bighead and silver carp, two varieties of Asian carp, said Jim Garvey, professor of fish ecology and management and director of the SIUC Fisheries and Aquaculture Center.

“The problem is that a lot of other fish species have the same diet as the carp,” Garvey said. “The worry is that when these carp arrive and become abundant, they’re going to eat the food the baby native fish eat and out-compete them.”

According to the Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee, carp can grow to more than one hundred pounds, average around 4 feet in length and consume up to 40 percent of their body weight each day. Their large size, avid appetite, rapid rate of reproduction and invasive movement pose a threat to the Illinois River, Great Lakes and surrounding ecosystems.

The silver carp are known to be easily startled by boat motors and can leap as high as ten feet out of the water. This behavior has caused direct harm to people and raises hazards to those partaking in recreational water sports.

Advertisement*

The jumping incidents are like a stampede, said Jeff Goelz, assistant director of Aquatics and Base Camp. Once a single fish is startled and begins to flee, the rest follow suit.

“If you’re driving a boat in a body of water up near Chicago, you better be wearing a helmet,” he said.

In their first year of life, Asian carp can grow to almost a foot long, Garvey said. They grow so rapidly it’s hard for any predator or predatory fish to control them unless they’re abundantly present.

“It’s very expensive to produce enough predatory fish to actually have a control on baby carp, particularly because they’re growing so fast. As for adults, there really are no natural predators,” Garvey said.

Keeping the carp out of the Great Lakes is the main concern.

One solution is an electrically charged barrier placed between the fish and Lake Michigan. Another suggested solution is to use targeted poisons to reduce the Asian carp population, but a major obstacle lies within the science and procedures of using poison.

Garvey said a poison must be approved by the federal government before use, which he said costs a tremendous amount of money. He said they would also have to use a selective toxin that would target Asian carp, with proof that it wouldn’t affect other organisms or harm people.

There’s nothing being developed for that toxin yet, though, Garvey said.

Most solutions raise concerns with sustainability, finances and ecology.

“The problem with poisoning and electric fences is that it’s not a very sustainable solution. The harvesting, creating a market and hopefully over-harvesting … you can see it being effective,” Whiles said. “You worry, though, that if you do develop an economic dependence or market, those profiting will want that market to be ultimately sustainable.”

Illinois received a $7 million initiative to monitor and research the Asian carp. The questions are whether harvesting will control the species and whether the carp are solely to blame for the struggles native fish are facing.

Carp have increased in abundance, but there have been a lot of environmental changes. This makes it very hard to differentiate between the Asian carp and the environmental effects, Garvey said.

Record hot summers and sedimentation in the Illinois River, he said, have created problems for the habitat as well.

Economically, the Asian carp market is slowly gaining momentum and could be a breakthrough in the job market. Interest has been shown in starting a carp processing plant in Grafton. Some topics in the marketing aspect will be the taste, locality and nutritional factors, Garvey said.

“We’ve found through research that they’re low in contaminates like mercury because they don’t eat other fish, and they contain high amounts of the right kinds of omega-3 fatty acids.” he said.

As far as the financial pressure to keep them around, harvest will not be enough to collapse the species. Also, the Illinois River is not the only body of water with an excess of Asian carp. The Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers are also infested.

Fisheries need to be able to use native fish and be flexible enough to deal with other sources to get the fish, Garvey said.

No solution will be the sole answer to this invasion, he said, but harvesting may at least reduce the propensity of the fish to move up towards the Great Lakes ecosystem.

“The rivers have been so modified in so many ways that the carp are just an added nuisance more than being the sole cause to the declines of the fish species we see here,” Garvey said. “We all have to remember that the rivers are so incredibly productive, there still might be plenty of food for all the fishes.”

Advertisement