Eavesdropping law raises eyebrows and questions

March 23, 2015

Citizens can film and record police in public under a new Illinois state law.

The new eavesdropping law took effect New Year’s Day in an effort to fix an earlier law that was struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court as unconstitutional last March.

However, critics of the new law say it is just as vague as its predecessor and whittles down judicial oversight of police investigations. The old law made it a crime to record police in public without consent.

Advertisement

The 27-page statute primarily does two things.

First, it outlines when people can record conversation and when they can not. People can record conversations in public, but not in private unless they have permission from all parties involved.

Second, the law shortens the process police go through when beginning surveillance on civilians’ private communication.

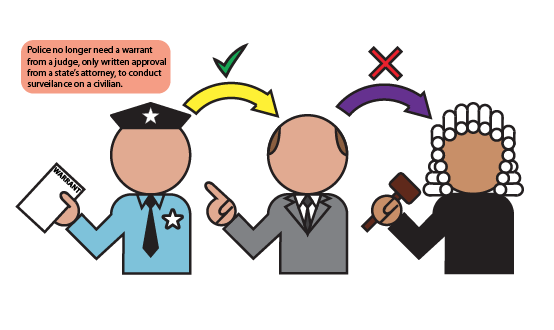

Traditionally, police needed to obtain a warrant to conduct surveillance on a citizen through the State’s Attorney who gets approval from a judge—ensuring a degree of separation and impartiality in the process.

Christian Baril, an attorney in Carbondale, said the judge is supposed to be detached and neutral when making a decision—on whether or not there is probable cause—to record a person’s private conversations.

However, with the new law, a judge’s permission is no longer needed for police to conduct surveillance on an individual if there is reason to believe they will engage in an incriminating conversation—regarding a qualifying offense—in the next 48 hours. Qualifying offenses range from felony violations of drug and violent crimes to sexual assault.

“What this basically means is the judge is cut out of the process in most felony investigations,” Baril said. “It’s going to be a lot easier for [police] to record a lot more people.”

Advertisement*

Illinois Rep. Elaine Nekritz, D-Northbrook, who sponsored the bill, said the law expands the number of crimes for which police can record citizens’ communications without getting a warrant.

“This was a request that we felt we had to include,” Nekritz said. “We felt we needed to include that language to get the votes that we needed to pass the bill.”

Now, police can request permission to eavesdrop on a civilian by submitting a partial name, nickname or alias and description of the person to the States Attorney’s office.

If the police do not have either of those bits of information, the law states the surveillance requests need information “that gives rise to reasonable cause to believe that the specified individual will participate in an [incriminating] conversation concerning a qualified offense.”

“Now the police just have to ask the State’s Attorney,” Baril said. “Which is kind of like if you were at a basketball game and you asked the team’s coach if the play was good instead of asking the referee. The State’s Attorney is most likely going to agree with the police every time.”

The Jackson Country State’s Attorney could not be reached for comment by press time.

In an interview regarding the new law, Carbondale interim Police Chief Jeff Grubbs declined to comment on the changes to how police get permission to conduct surveillance on civilians.

Recording civilians and police in public

Besides restructuring the way police can eavesdrop on civilians, the law prohibits civilians from recording one another, including police—if at least one party has a reasonable expectation for privacy—unless all parties involved have consented to the recording.

“I felt it was very important to maintain the expectation that the conversations that citizens have be private,” Nekritz said.

The law states the eavesdropping of an oral or electronic conversation of any law enforcement officer, while in the performance of his or her official duties, is a Class 3 felony.

The law defines eavesdropping as using a recording device in a secretive manner to record, transcribe or listen in on a private conversation.

Civilians are allowed to video or audio record police officers when in public, Nekritz said.

“Until we get direction through the courts, then, we will continue to allow audio/video recording of police officers in the public,” Grubbs said.

The law protects peoples’ right to film one another in public, unless “one or more of the parties intended the communication to be of a private nature under circumstances reasonably justifying that expectation.”

However, William A. Schroeder, professor emeritus at the SIU School of Law, said the law is unconstitutionally vague.

“How do I know when you expect privacy? I have no idea,” he said.

Schroeder, who thinks people should be recording police all of the time, said the law does not protect honest citizens.

“It’s a law designed to protect liars and cheats,” Schroeder said. “If you offered me a bribe right now, then it’s your word against mine. If I have a recording or you have a recording, we’ve memorialized it, so we can get rid of the swearing contest and we preserve the truth.”

Adam Riley, a second year law student from Karnak, said the statute discourages the recording of the police because average citizens are not going to know when they can legally record somebody.

“Police are able to record you from their police car or from their body cameras or whatever, so you should be able to do the same,” Riley said.

Riley, who is writing an article on the eavesdropping statute for the Southern Illinois University Law Journal, said a bulk of the confusion arises when determining if citizens have the right to film police on private property.

“When an officer comes to, say, your house or your dorm room—with a warrant or without a warrant—so they’re in a private area, and say you want to record them for whatever reason,” Riley said. “Do they have an expectation of privacy in a private area?”

Viral video sparks conversation

Matt Fedora, a senior from Aurora studying speech communication, drew attention online after impulsively deciding to film a police officer who he says was sleeping on the job on an early morning in January.

At the end of the two-minute video, which has 56,000 views on Facebook, the Carbondale police officer tells Fedora it is illegal to record police officers in public.

“The allegations which were made during the video recording were largely unsubstantiated,” Grubbs said, referring to the officer’s claim about the legality of the recording.

Grubbs said the department’s investigation of the incident is now over. He would not disclose if the investigation revealed whether the officer was sleeping or not and would not release the name of the officer in the video.

Fedora, who published the video on Jan. 16, said he had no intention of filming the officer as he approached the squad car, until he saw the officer sleeping.

“If a citizen is filming a police officer acting inappropriately, under no circumstance should that be illegal,” Fedora said. “What makes the United States the United States is the ability to do just that.”

The part of the eavesdropping law relating to the State’s Attorney being able to provide police with surveillance permission has a sunset provision, and expires on Jan. 1, 2018.

Advertisement